Credit: Celeste Simon, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Cell Press

PHILADELPHIA – Kidney cancer, one of the ten most prevalent malignancies in the world, has increased in incidence over the last decade, likely due to rising obesity rates. The most common subtype of this cancer is "clear cell" renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), which exhibits multiple metabolic abnormalities, such as highly elevated stored sugar and fat deposition.

By integrating data on the function of essential metabolic enzymes with genetic, protein, and metabolic abnormalities associated with ccRCC, researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania determined that enzymes important in multiple pathways are universally depleted in ccRCC tumors. They published their findings this week in Cell Metabolism.

"Kidney cancer develops from an extremely complex set of cellular malfunctions," said senior author Celeste Simon, PhD, the scientific director of the Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute and a professor of Cell and Developmental Biology. "That's why we approached studying its cause from many perspectives."

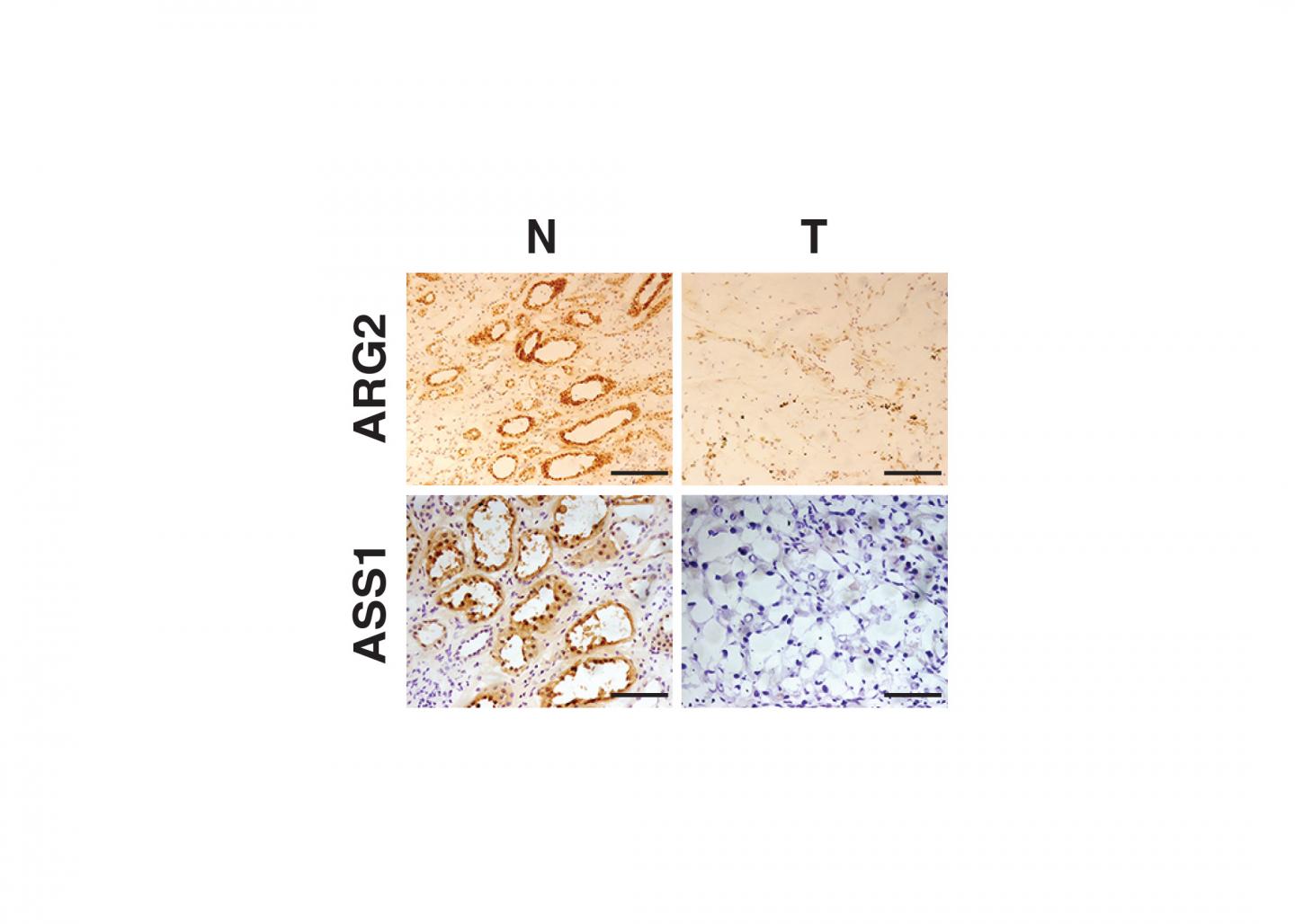

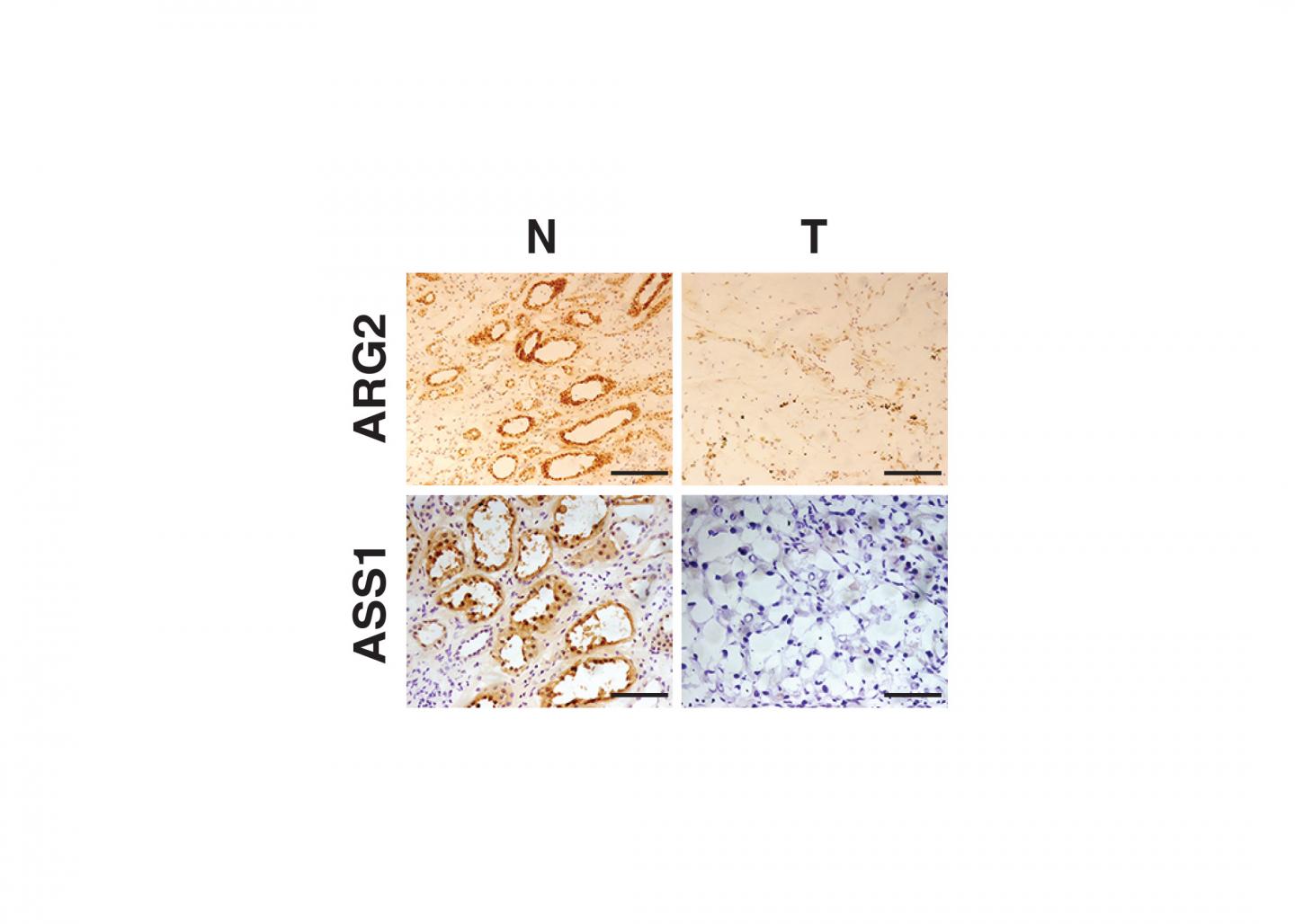

Using human tissue provided by the National Cancer Institute's Cooperative Human Tissue Network and Penn Medicine physicians Naomi Haas, MD, an associate professor of Hematology/Oncology, and Priti Lal, MD, an associate professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, the team found that the expression of certain enzymes is strongly repressed in ccRCC tumors. For example, reduced activity of one enzyme, arginase, promotes ccRCC tumor growth through at least two distinct biochemical pathways. One is by conserving a critical molecular cofactor and the second is by avoiding toxic accumulation of organic compounds. The enzymes whose activities are depressed are involved in the breakdown of urea, a byproduct of protein being used in the human body. In addition, loss of these enzymes results in decreased ability of the immune system to eradicate these tumors.

"Pharmacological approaches to restore the expression of urea cycle enzymes would greatly expand treatment options for ccRCC patients, whose current therapies only benefit a small subset," Simon said.

In the future, the researchers aim to test such epigenetic drugs as HDAC and DNA methylase inhibitors to turn on genes for multiple lost enzymes in renal cancer. The study was completed by researchers at both Penn Medicine and Children's Hospital of Philadelphia who specialize in studying metabolic abnormalities in children.

###

Coauthors are Joshua D. Ochocki, Sanika Khare, Markus Hess, Daniel Ackerman, Bo Qiu, Jennie I. Daisak, Andrew J. Worth, Nan Lin, Pearl Lee, Hong Xie, Bo Li Bradley Rubbenhorst, Tobi G. Maguire, Katherine L. Nathanson, James C. Alwine, Ian A. Blair, Itzhak Nissim, and Brian Keith.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (CA192758, CA101871, CA104838) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $7.8 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine has been ranked among the top medical schools in the United States for more than 20 years, according to U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $405 million awarded in the 2017 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and Penn Presbyterian Medical Center — which are recognized as one of the nation's top "Honor Roll" hospitals by U.S. News & World Report — Chester County Hospital; Lancaster General Health; Penn Medicine Princeton Health; Penn Wissahickon Hospice; and Pennsylvania Hospital – the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Additional affiliated inpatient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region include Good Shepherd Penn Partners, a partnership between Good Shepherd Rehabilitation Network and Penn Medicine, and Princeton House Behavioral Health, a leading provider of highly skilled and compassionate behavioral healthcare.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2017, Penn Medicine provided $500 million to benefit our community.

Media Contact

Karen Kreeger

[email protected]

215-459-0544

@PennMedNews

http://www.uphs.upenn.edu/news/