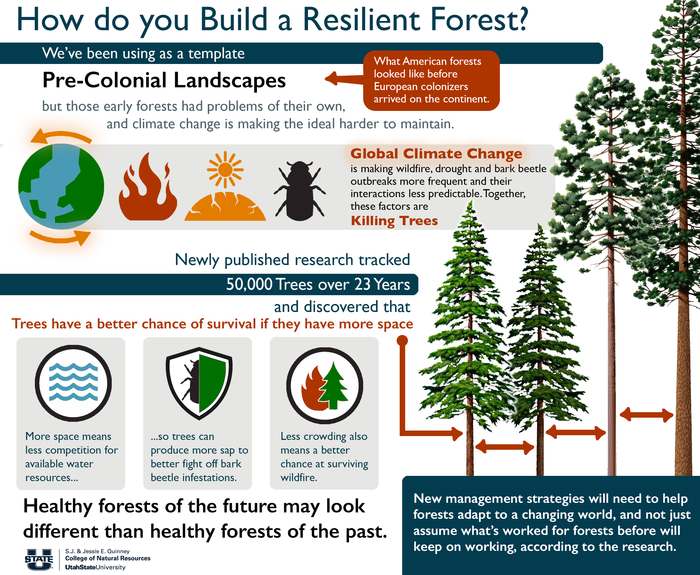

For many, an ideal forest is one that looks the same as it did before European colonizers arrived. As today’s forests are hit with disturbances like fire, drought, and insect invasions, restoration efforts often attempt to nudge the landscape back to this ‘natural’ state. But historical conditions are becoming increasingly hard to achieve in a changing world, according to new research. Managers need to consider new strategies for building resilient forests, according to Tucker Furniss and Jim Lutz, from Utah State University’s Department of Wildland Resources in the S.J. & Jessie E. Quinney College of Natural Resources.

Credit: Infographic by Lael Gilbert, Utah State University

For many, an ideal forest is one that looks the same as it did before European colonizers arrived. As today’s forests are hit with disturbances like fire, drought, and insect invasions, restoration efforts often attempt to nudge the landscape back to this ‘natural’ state. But historical conditions are becoming increasingly hard to achieve in a changing world, according to new research. Managers need to consider new strategies for building resilient forests, according to Tucker Furniss and Jim Lutz, from Utah State University’s Department of Wildland Resources in the S.J. & Jessie E. Quinney College of Natural Resources.

In the age of large-scale fires, forest-wide beetle invasions, and frequent drought, maintaining ‘ideal’ historical conditions is becoming increasingly unrealistic, the researchers say. Disturbances are coming at forests more frequently, and the changing climate makes things unpredictable. Recreating historical conditions has been a key strategy for restoration efforts, but today’s novel conditions require different strategies. Specifically, the research shows that lower crowding for trees can increase chances of survival after fire. Results from two long-term studies (covering 23 years and more than 50,000 individual trees) show that chances for long-term tree survival increased when trees had more space, by reducing competition and helping trees recover from fire more quickly.

Over the years, the team performed tens of thousands of post-mortems on dead trees in the Sierra Nevada mountains to identify the cause of demise. They analyzed data and found that in crowded forests, trees were less tolerant of fire damage, and were more susceptible to post-fire bark beetle attack. In more open forests, though, trees could tolerate higher levels of fire damage, even when fire burned during extreme drought. Drought usually increases a forest’s susceptibility to both fire and bark beetle infestations, but this work shows that lower forest density can actually reduce the risk of both. Alleviating the stress that occurs when close neighbors compete for limited water resources lets trees use sap to fend off beetle attacks, and it helps them heal after fire.

Results from this research shed light on forest restoration strategies that could be used when historical reference conditions are not a viable option, a critical step in the effort to help forests adapt to a changing world, the authors say.

“Using historical conditions as an ideal example of a healthy forest may not be practical moving forward,” Furniss said. Forests from the pre-settlement era had their own problems after all, he said. And even if those ecosystems were successful at overcoming the disturbances of their time, those evolutionary strategies don’t necessarily translate to resilience today, in a world defined by climate change.

Journal

Ecological Applications

Article Title

Crowding, climate, and the case for social distancing among trees

Article Publication Date

30-Jul-2021