LOGAN, UTAH, USA — What’s black and white and red all over? It might be a velvet ant. But discerning which one could be head-scratching challenge. It’s a challenge made much easier, however, by a new field guide compiled by Utah State University biologist Joseph Wilson and USU alum Kevin Williams (Ph.D. 2012), along with Texas Tech colleague Aaron Pan.

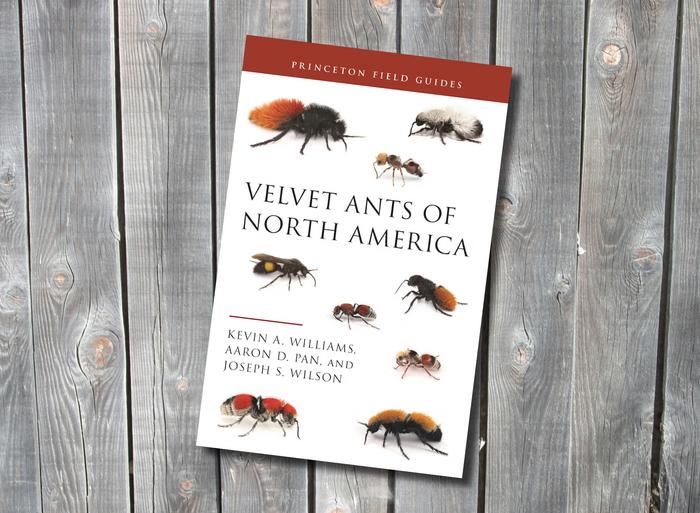

Credit: Princeton University Press

LOGAN, UTAH, USA — What’s black and white and red all over? It might be a velvet ant. But discerning which one could be head-scratching challenge. It’s a challenge made much easier, however, by a new field guide compiled by Utah State University biologist Joseph Wilson and USU alum Kevin Williams (Ph.D. 2012), along with Texas Tech colleague Aaron Pan.

Released Feb. 13, the trio’s book, “Velvet Ants of North America,” is a first-of-its-kind volume aimed at helping both professional and amateur entomologists identify and learn about the more than 450 known species of the Mutillidae family in North America and beyond.

“Velvet ants, which are actually wasps, are an underrepresented group,” says Wilson, an evolutionary ecologist and associate professor of biology at Utah State University Tooele. “There are very few resources to help hobbyists, students or even academics seeking information.”

To remedy this situation, Wilson teamed with Williams, associate insect biosystematist with the California Department of Food and Agriculture, and Pan, executive director of the Museum of Texas Tech University, to provide a comprehensive reference for naturalists, scientific researchers, museum specialists and outdoor enthusiasts at all learning levels.

“We initially considered preparing a guide about velvet ants of northern Texas, where the wasps are abundant, but decided to broaden the scope to North America,” Wilson says. “We also included information about velvet ants in other areas of the world.”

Most field guides, he says, arrange species in taxonomic sequence, based on the species’ evolutionary history. But the scientists chose a different approach for the velvet ants because the wasps employ a flashy PPE called mimicry.

“Mimicry is a form of evolutionary defense in which one animal copies another of a different species in appearance, actions or sound,” says Wilson, who, with colleagues, identified North American velvet ants as one of the world’s largest known Müllerian mimicry complexes in 2015.

Because velvet ants sport an immense array of bright colors, the scientists chose to organize the field guide primarily by color patterns, rather than taxonomic sequence.

“We borrowed this approach from field guides for wildflowers,” Wilson says. “This makes our guide unique as an insect guide. It also includes taxonomic keys and gender descriptions to help identify species. It’s super thorough — we’ve got you covered.”

Velvet ants’ immense palette is just one of several defenses in their unique arsenal poised to keep predators at bay. Their powerful sting, for one, earned the wasps a formidable rank on the Schmidt Sting Pain Index, developed by American entomologist Justin O. Schmidt (1947-2023).

“Velvet ants are known colloquially as ‘cow killers’ because their venom packs a powerful punch,” Wilson says. “In addition, their ‘sting’ — the scientific term for what many of us refer to as a ‘stinger’ — is agile and half as long as the wasp itself. This enables the insect to inject venom into a predator from varied angles and free itself.”

The wasps also make noise.

“They squeak to startle and warn predators and they emit pungent chemical secretions,” Wilson says.

Rounding out their armor, velvet ants have a hard exoskeleton that buys the wasp some time to inflict a stinging defense before a hunter can take a fatal bite.

“We think velvet ants are some of the coolest members of the animal kingdom,” Wilson says. “We look forward to sharing our guide.”

The 440-page guide is published by Princeton University Press.