New court actions upholding climate stability as a protected right are needed to break the climate change impasse, an Oregon State University economist concludes in a just-published paper.

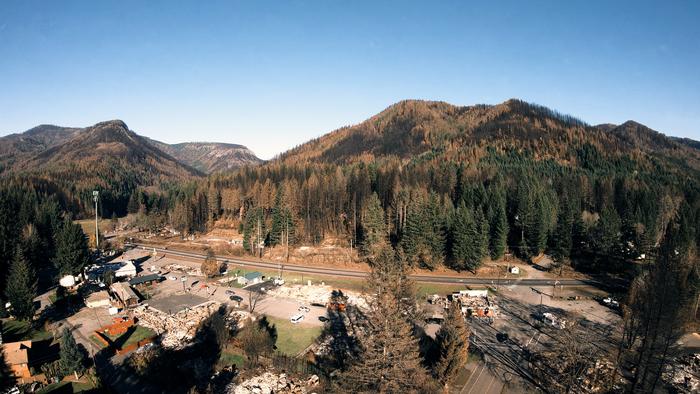

Credit: Oregon State University

New court actions upholding climate stability as a protected right are needed to break the climate change impasse, an Oregon State University economist concludes in a just-published paper.

Drawing on empirical studies, theoretical research and climate change policy models, Bill Jaeger also concludes that 30 years of international treaties addressing climate change, including most recently the Paris Agreement of 2015, are hopelessly stymied.

“This is in large part because of the long delays between when the costs of reducing carbon emissions are paid and the length of time until most of the benefits are realized,” Jaeger said. “Put another way, a majority of the voting age public will not support climate policies whose benefits arrive mainly after they die.”

Despite those dire findings, Jaeger also concludes there is a potential solution: courts recognizing that climate rights are protected by existing laws. Climate rights refers to a legally-binding right to a safe and stable climate. Courts in the Netherlands and to some degree Ukraine, Philippines and Pakistan have concluded their laws protect climate rights.

“If more courts continue to find that climate stability is a protected right, that could add leverage. It would effectively give a voice, if not a vote, to future generations,” said Jaeger, a professor of applied economics in the College of Agricultural Sciences.

In the paper, published in PLOS Climate, Jaeger looks at past attempts to stabilize the climate through three domains: domestic, international and intergenerational.

His analysis found that the cost of adopting domestic climate policies is generally manageable. International agreements, he found, face major obstacles because of the high costs of negotiating, implementing, administering, maintaining, monitoring and enforcing them and incentives for countries to not abide by agreements but take advantage of the benefits.

Jaeger finds, however, that the intergenerational domain is the most problematic and something that has not been fully recognized in past research. It’s problematic because of the decades long lag between carbon dioxide emissions reductions and mitigation benefits, he said. In other words, he said most people tend not to support costly actions today to address climate change because they won’t see the benefits in their lifespans.

“Most people will not agree to actions which makes them worse off,” Jaeger said. “This explains the lack of progress in addressing climate change despite 30 years of trying.”

In addition to the international legal cases Jaeger cites, he also references Juliana v. United States, a lawsuit brought in 2015 on behalf of a group of Oregon children. It centers on constitutional rights to life, liberty and property, as well as the equal protection principles in the 14th Amendment.

The case is still working its way through the legal system, although a court in an earlier decision in the case concluded it should be decided by the political branches or the electorate at large.

This led Jaeger to conclude that the court “overlooks the unique nature of the problem: future generations do not vote and cannot lobby Congress on their own behalf. The courts ignore this at their, and our, peril. This represents a unique and potentially powerful opportunity to recognize the public’s right to a stable climate. This recognition of climate rights would increase support (including legal mandates) for climate actions beyond what is reflected in the current generation’s self-interests.”

Journal

PLOS Climate