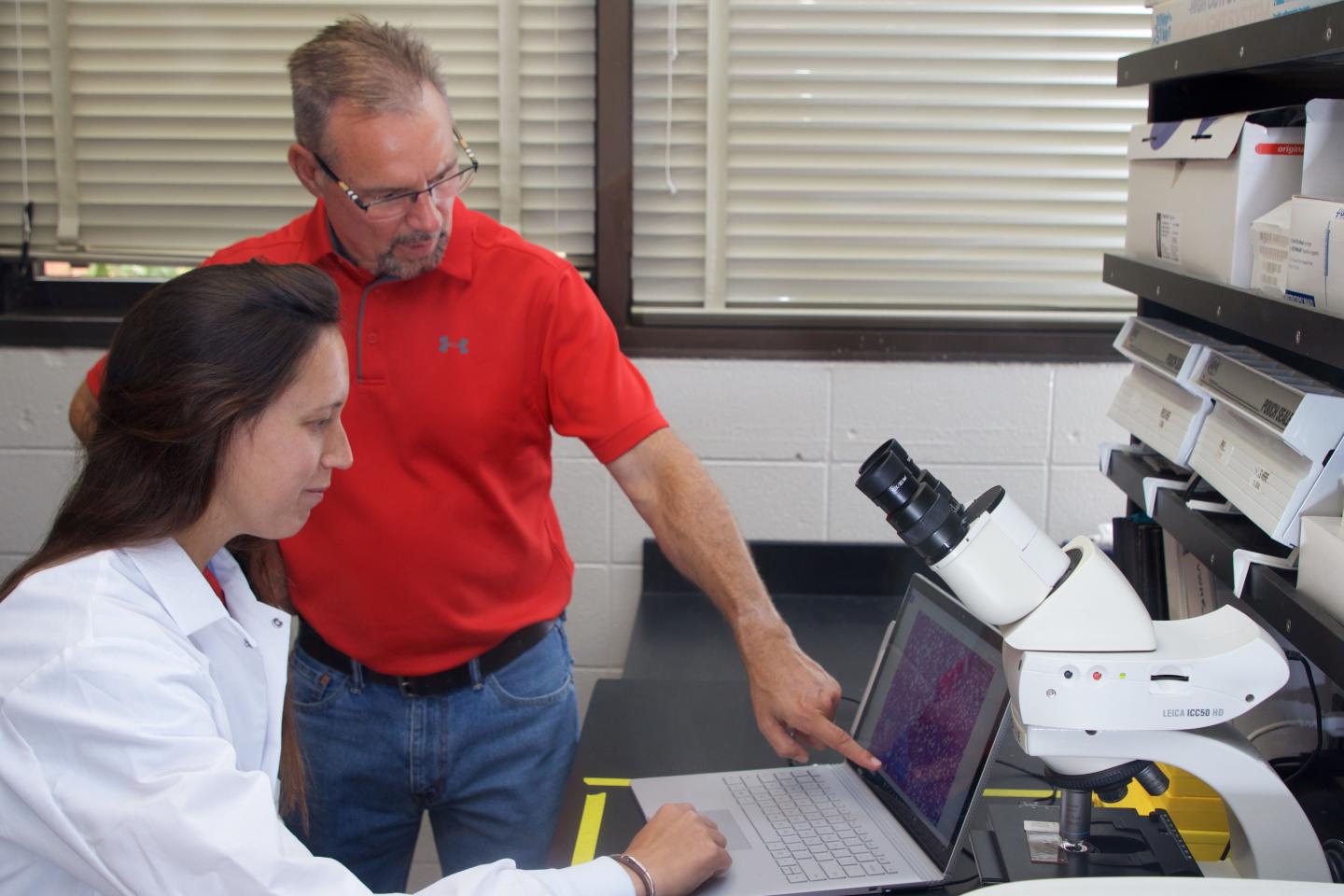

Clemson University scientist William Baldwin has been awarded a National Institutes of Health Research Enhancement Award (R15)

Credit: Clemson University

CLEMSON, South Carolina – Clemson University scientist William Baldwin has been awarded a National Institutes of Health Research Enhancement Award (R15) to build on his past work that explored the complex interactions of diet and environmental toxicants.

One important goal of R15 awards is to expose students to research. Baldwin plans to enlist the help of a new doctoral student and several undergraduates on the front line of this new endeavor.

The three-year, $377,000 grant will enable Baldwin, a professor in the College of Science’s Department of Biological Sciences, to further his research on the role Cyp2b genes play in obesity. Cyp2b is part of a superfamily of enzymes. Baldwin will also focus on the human CYP2B6 gene’s role in the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and its progression to the more severe nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

Baldwin’s past research showed that only male Cyp2b-null mice are more obese than wild-type mice when both are fed a high-fat diet. Females did not show an increase in obesity. In addition, male Cyp2b-null mice had increased fatty liver disease even while not being fed a high-fat diet. Baldwin’s lab published research earlier this year that demonstrated that increased NAFLD development does not necessarily lead to progressive NASH. It also further indicated a role for Cyp2b in fatty liver disease that differs based on gender.

“This new grant has three purposes,” said Baldwin, who is graduate program coordinator for Biological Sciences. “One is to determine if the human CYP2B6 gene does what the mouse genes do. Is it able to exhibit anti-obesity fatty acid metabolism? We assume that it does, because when we take the gene away in mice, you get the obesity and fatty liver disease in males, but this has not been tested with the human gene.”

The new work will also continue to look at fatty liver disease in humanized models.

“There was some data that indicated that females didn’t progress the same way to NASH,” Baldwin said. “They were almost protected. These genes seem to be helpful in some way toward developing obesity and fatty liver disease. Why is this? We’re looking at the role of CYP2B6 in metabolizing polyunsaturated fatty acids. We have some candidate fatty acid products that leave the liver and signal various organs such as adipose and skeletal muscle what they should do in response to the diet we just ate.”

The last thing is looking at a potent inhibitor, PFOS (perfluorooctane sulfonate), a toxicant found in our waterways and groundwater.

“PFOS enters our water mainly from firefighting foams,” Baldwin said. “We’re looking at PFOS and how it interacts with CYP2B6 to cause obesity and changes in fatty acid metabolism. PFOS is a potent metabolic disruptor.”

Preliminary data suggests PFOS toxicity is greater if you have high amounts of CYP2B6. But if you combine a high-fat diet and high amounts of CYP2B6, the CYP2B6 might be protective from PFOS; however this could be a dietary interaction. The real-world possibility is a multiplier effect: eating a healthy diet might result in CYP2B6 being protective, while eating a poor diet might result in unhealthy metabolites – oxylipins that could be a negative. All of this interacts with exposure to environmental toxicants.

“A thin person might not react the same way to a chemical as an obese person would react to the chemical,” Baldwin said. “The interactions are complex and based on diet and fat stores.”

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health Research Enhancement Award under Award Number ES017321. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

###

Media Contact

Jim Melvin

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/