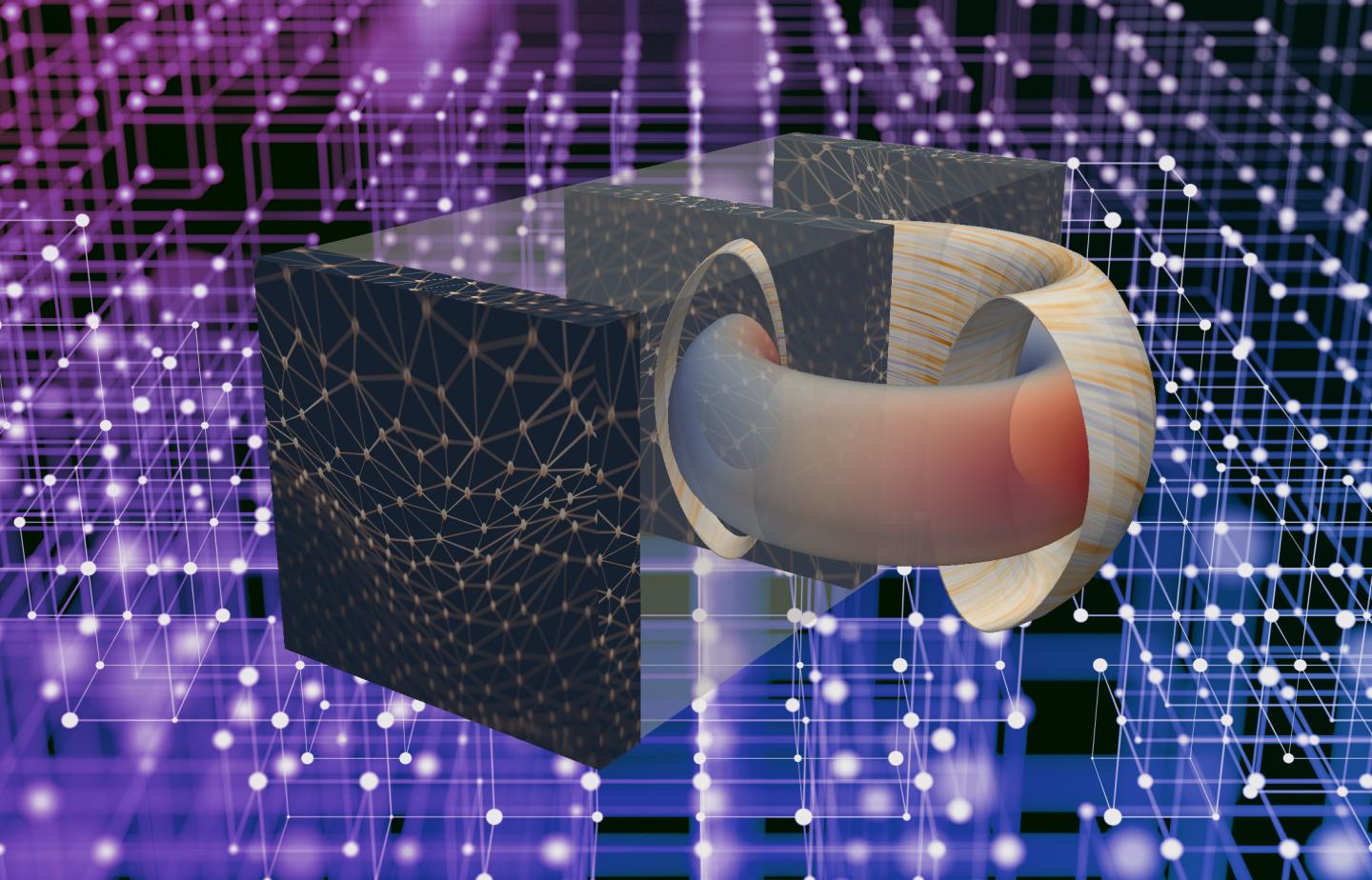

Credit: Eliot Feibush/PPPL and Julian Kates-Harbeck/Harvard University

Artificial intelligence (AI), a branch of computer science that is transforming scientific inquiry and industry, could now speed the development of safe, clean and virtually limitless fusion energy for generating electricity. A major step in this direction is under way at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) and Princeton University, where a team of scientists working with a Harvard graduate student is for the first time applying deep learning — a powerful new version of the machine learning form of AI — to forecast sudden disruptions that can halt fusion reactions and damage the doughnut-shaped tokamaks that house the reactions.

Promising new chapter in fusion research

“This research opens a promising new chapter in the effort to bring unlimited energy to Earth,” Steve Cowley, director of PPPL, said of the findings, which are reported in the current issue of Nature magazine. “Artificial intelligence is exploding across the sciences and now it’s beginning to contribute to the worldwide quest for fusion power.”

Fusion, which drives the sun and stars, is the fusing of light elements in the form of plasma — the hot, charged state of matter composed of free electrons and atomic nuclei — that generates energy. Scientists are seeking to replicate fusion on Earth for an abundant supply of power for the production of electricity.

Crucial to demonstrating the ability of deep learning to forecast disruptions — the sudden loss of confinement of plasma particles and energy — has been access to huge databases provided by two major fusion facilities: the DIII-D National Fusion Facility that General Atomics operates for the DOE in California, the largest facility in the United States, and the Joint European Torus (JET) in the United Kingdom, the largest facility in the world, which is managed by EUROfusion, the European Consortium for the Development of Fusion Energy. Support from scientists at JET and DIII-D has been essential for this work.

The vast databases have enabled reliable predictions of disruptions on tokamaks other than those on which the system was trained — in this case from the smaller DIII-D to the larger JET. The achievement bodes well for the prediction of disruptions on ITER, a far larger and more powerful tokamak that will have to apply capabilities learned on today’s fusion facilities.

The deep learning code, called the Fusion Recurrent Neural Network (FRNN), also opens possible pathways for controlling as well as predicting disruptions.

Most intriguing area of scientific growth

“Artificial intelligence is the most intriguing area of scientific growth right now, and to marry it to fusion science is very exciting,” said Bill Tang, a principal research physicist at PPPL, coauthor of the paper and lecturer with the rank and title of professor in the Princeton University Department of Astrophysical Sciences who supervises the AI project. “We’ve accelerated the ability to predict with high accuracy the most dangerous challenge to clean fusion energy.”

Unlike traditional software, which carries out prescribed instructions, deep learning learns from its mistakes. Accomplishing this seeming magic are neural networks, layers of interconnected nodes — mathematical algorithms — that are “parameterized,” or weighted by the program to shape the desired output. For any given input the nodes seek to produce a specified output, such as correct identification of a face or accurate forecasts of a disruption. Training kicks in when a node fails to achieve this task: the weights automatically adjust themselves for fresh data until the correct output is obtained.

A key feature of deep learning is its ability to capture high-dimensional rather than one-dimensional data. For example, while non-deep learning software might consider the temperature of a plasma at a single point in time, the FRNN considers profiles of the temperature developing in time and space. “The ability of deep learning methods to learn from such complex data make them an ideal candidate for the task of disruption prediction,” said collaborator Julian Kates-Harbeck, a physics graduate student at Harvard University and a DOE-Office of Science Computational Science Graduate Fellow who was lead author of the Nature paper and chief architect of the code.

Training and running neural networks relies on graphics processing units (GPUs), computer chips first designed to render 3D images. Such chips are ideally suited for running deep learning applications and are widely used by companies to produce AI capabilities such as understanding spoken language and observing road conditions by self-driving cars.

Kates-Harbeck trained the FRNN code on more than two terabytes (1012) of data collected from JET and DIII-D. After running the software on Princeton University’s Tiger cluster of modern GPUs, the team placed it on Titan, a supercomputer at the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility, a DOE Office of Science User Facility, and other high-performance machines.

A demanding task

Distributing the network across many computers was a demanding task. “Training deep neural networks is a computationally intensive problem that requires the engagement of high-performance computing clusters,” said Alexey Svyatkovskiy, a coauthor of the Nature paper who helped convert the algorithms into a production code and now is at Microsoft. “We put a copy of our entire neural network across many processors to achieve highly efficient parallel processing,” he said.

The software further demonstrated its ability to predict true disruptions within the 30-millisecond time frame that ITER will require, while reducing the number of false alarms. The code now is closing in on the ITER requirement of 95 percent correct predictions with fewer than 3 percent false alarms. While the researchers say that only live experimental operation can demonstrate the merits of any predictive method, their paper notes that the large archival databases used in the predictions, “cover a wide range of operational scenarios and thus provide significant evidence as to the relative strengths of the methods considered in this paper.”

From prediction to control

The next step will be to move from prediction to the control of disruptions. “Rather than predicting disruptions at the last moment and then mitigating them, we would ideally use future deep learning models to gently steer the plasma away from regions of instability with the goal of avoiding most disruptions in the first place,” Kates-Harbeck said. Highlighting this next step is Michael Zarnstorff, who recently moved from deputy director for research at PPPL to chief science officer for the laboratory. “Control will be essential for post-ITER tokamaks – in which disruption avoidance will be an essential requirement,” Zarnstorff noted.

Progressing from AI-enabled accurate predictions to realistic plasma control will require more than one discipline. “We will combine deep learning with basic, first-principle physics on high-performance computers to zero in on realistic control mechanisms in burning plasmas,” said Tang. “By control, one means knowing which ‘knobs to turn’ on a tokamak to change conditions to prevent disruptions. That’s in our sights and it’s where we are heading.”

###

Support for this work comes from the Department of Energy Computational Science Graduate Fellowship Program of the DOE Office of Science and National Nuclear Security Administration; from Princeton University’s Institute for Computational Science and Engineering (PICsiE); and from Laboratory Directed Research and Development funds that PPPL provides. The authors wish to acknowledge assistance with high-performance supercomputing from Bill Wichser and Curt Hillegas at PICSciE; Jack Wells at the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility; Satoshi Matsuoka and Rio Yokata at the Tokyo Institute of Technology; and Tom Gibbs at NVIDIA Corp.

PPPL, on Princeton University’s Forrestal Campus in Plainsboro, N.J., is devoted to creating new knowledge about the physics of plasmas — ultra-hot, charged gases — and to developing practical solutions for the creation of fusion energy. The Laboratory is managed by the University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, which is the largest single supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Media Contact

John Greenwald

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.