A Remarkable Neanderthal Discovery in Crimea Sheds New Light on Eurasian Migrations

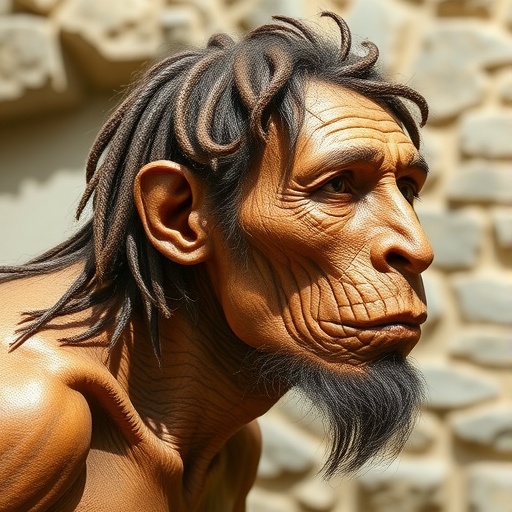

In a groundbreaking new study performed by an international team led by the University of Vienna, a tiny 5-centimeter fragment of a Neanderthal bone, uncovered from the Starosele Cave in the Crimean Peninsula, has revealed profound insights into the migration patterns of ancient humans across Eurasia during the Late Pleistocene epoch, approximately 40,000 to 50,000 years ago. The bone, affectionately dubbed “Star 1” after its excavation site, was identified using an advanced biomolecular technique that isolates ancient proteins to distinguish human remains from animal fossils. Subsequent genetic analysis astonishingly linked this specimen most closely to Neanderthals that once lived in Siberia’s Altai Mountains, located over 3,000 kilometers away from Crimea, highlighting unexpected long-distance connections across the Eurasian landmass.

Starosele Cave, a rock shelter in the Crimean Peninsula, has been a site of archaeological interest since 1952 but had until now yielded only post-medieval human remains. The prevailing assumption was that no Palaeolithic human fossils had been found there. However, by applying cutting-edge biomolecular analyses to an assemblage of over 150 fragmented bones, researchers from the University of Vienna uncovered a small piece, measuring just under 5 centimeters in length, that was definitively identified as human. This discovery reframes the archaeological narrative of Starosele, placing it squarely within a Palaeolithic context for the first time and providing crucial new data about human presence during the Late Pleistocene in this region.

One of the primary analytical methods employed in this research was Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry (ZooMS), a novel palaeoproteomic technique that profiles collagen peptides extracted from fragmented bones. This technique operates by assessing molecular weight differences in collagen’s peptide bonds, allowing researchers to distinguish species even from minuscule and taxonomically indeterminate bone fragments. Among the sampled fragments, 93% were identified as belonging to herbivores such as horses and deer, alongside smaller quantities from mammoths and wolves. This assemblage suggests a strong emphasis on horse hunting amid the Palaeolithic populations that occupied the Crimean Peninsula. Remarkably, one fragment diverged significantly, being identified as human—a breakthrough find from this site’s faunal assemblage.

To further characterize the fragment, micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) imaging was undertaken, revealing that the bone likely originated from a human femur. The bone was subjected to ultra-refined radiocarbon dating techniques involving the latest decontamination protocols, which established an age range of approximately 46,000 to 44,000 years. This timing securely positions the bone within the Palaeolithic period, a critical era for understanding hominin evolution and interaction with environmental shifts during the Late Pleistocene. The calibrated radiocarbon date also dispels earlier assumptions that all human remains from Starosele belonged exclusively to much later periods.

The excitement within the research team was palpable when these analyses indicated the bone belonged to a Palaeolithic human. Emily M. Pigott, a doctoral researcher at the University of Vienna and lead author, recounts that this discovery occurred on the analysis of just her 46th bone via ZooMS, emphasizing the rarity and significance of such finds. The bone, named “Star 1,” extends the sparse and invaluable record of hominin fossils from the crucial period when Neanderthals were gradually being displaced by Homo sapiens across Eurasia. The genetic information preserved within this tiny specimen thus offers unprecedented views into the evolutionary dynamics of our ancient relatives.

Subsequent genomic analysis conducted by co-authors Konstantina Cheshmedzhieva and Martin Kuhlwilm revealed that the “Star 1” individual belongs unequivocally to the Neanderthal lineage. Intriguingly, this Neanderthal was genetically closest to individuals recovered from the Altai region in Siberia, a population separated by more than 3,000 kilometers from Crimea. Additional affinities were observed with Neanderthals from Europe, including remains from Croatia. This genetic evidence strongly supports scenarios of wide-ranging Neanderthal migrations and gene flow over vast distances throughout Eurasia, painting a much more interconnected picture of Neanderthal dispersal than previously recognized.

Prior to this discovery, the notion that Neanderthals primarily occupied relatively localized and fragmented habitats across Europe and western Asia was commonly held. However, the newly uncovered genetic ties from Crimea to Siberia reinforce the hypothesis that Neanderthals were capable of inhabiting, traversing, and interlinking disparate regions across the Eurasian steppes. This insight places Crimea as a critical nexus within a continental migration corridor utilized repeatedly by Neanderthals during the Late Pleistocene, suggesting complex population dynamics and potentially adaptive strategies to exploit diverse ecological zones.

Climate modeling efforts contributed crucial contextualization to this story. Researchers Elke Zeller and Axel Timmermann, leveraging palaeoclimatic and human habitat reconstructions, identified two notable climatic intervals—approximately 120,000 and 60,000 years ago—that presented favorable environmental conditions fostering Neanderthal mobility. These periods, marked by more temperate and resource-rich environments during so-called Last Interglacial phases, would have lowered migratory barriers and allowed Neanderthals to track seasonal and geographic shifts in animal herds, facilitating their long-distance movement across Eurasia. This aligns with emerging views that hominin mobility strategies were responsive to climate oscillations and resource availability.

The implications of this study underscore not only the technological advances enabling the study of tiny, fragmentary fossil remains but also the intellectual breakthroughs gained from integrative methodologies combining biomolecular approaches, advanced imaging, genetic sequencing, and environmental modeling. Senior author Professor Tom Higham highlights how this multipronged analytical framework can uncover previously hidden human fossil evidence, substantially enriching our understanding of the intricate evolutionary history of hominins. The revelation of extensive Neanderthal movement capabilities challenges decades-old perspectives that ascribed complex migration and adaptation almost exclusively to anatomically modern humans.

The discovery of the “Star 1” Neanderthal bone fragment is a pivotal contribution that reinvigorates the narrative of human evolutionary research. It speaks to Neanderthals’ resilience, adaptability, and broad geographic dispersal abilities during the twilight of their tenure as a species. Positioning Crimea as a central hub in these movements reframes Eurasian prehistoric archaeology and urges reconsideration of hominin socioecological models. As more ancient remains continue to be examined with refined technologies, the portrait of Neanderthals as isolated or regionally constrained populations will undoubtedly give way to more complex, interconnected scenarios.

Beyond providing direct evidence of Neanderthal migration, this study exemplifies the power of interdisciplinary collaboration across continents, harnessing biomolecular science, palaeoanthropology, genetics, and climatology. The combination of specialized expertise was essential in piecing together an intricate puzzle involving minuscule fossil fragments and deciphering their broader implications for human prehistory. The discovery not only enriches the paleontological record but also prompts innovative inquiry into how our ancient relatives navigated shifting landscapes and climate episodes during the Pleistocene.

With this research published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the field is poised for a wave of new investigations employing ZooMS and genetic analytic techniques across Eurasian fossil collections. The potential for uncovering further hidden human remains and reconstructing migration corridors opens promising vistas for understanding the complex evolutionary narrative shared by Neanderthals and modern humans alike. As technology advances, it becomes increasingly evident that our prehistoric past is far richer and more intertwined than previous generations of scholars ever imagined.

This seminal discovery from the Crimean Peninsula marks a new chapter in the study of Neanderthals, illustrating their remarkable mobility, genetic diversity, and ecological flexibility. It challenges established paradigms while enriching our knowledge of Late Pleistocene Eurasian hominin dispersals. As small fragments yield monumental insights, the legacy of “Star 1” extends across space and time, connecting ancient peoples to the broader story of human evolution.

Subject of Research: Late Neanderthal migration and genetic connections across Eurasia during the Late Pleistocene

Article Title: A new late Neanderthal from Crimea reveals long-distance connections across Eurasia

News Publication Date: 27-October-2025

Web References: Not provided

References: DOI 10.1073/pnas.2518974122

Image Credits: Prof. Tom Higham, University of Vienna

Tags: Altai Mountains Neanderthalsancient human migrationsarchaeological methods for ancient bonesbiomolecular techniques in archaeologyCrimean Peninsula discoveriesEurasian migration patternsgenetic links between NeanderthalsLate Pleistocene archaeologylong-distance Neanderthal connectionsNeanderthal DNA analysisNeanderthal fossil discoveriesStarosele Cave excavations