In the middle of the South Atlantic, there’s a patch of sea almost devoid of life. There are no birds, few fish, not even much plankton. But researchers report that they’ve found buried treasure under the empty waters: ancient DNA hidden in the muck of the sea floor, which lies 5000 meters below the waves.

The DNA, from tiny, one-celled sea creatures that lived up to 32,500 years ago, is the first to be recovered from the abyssal plains, the deep-sea bottoms that cover huge stretches of Earth. In a separate finding published this week, another research team reports teasing out plankton DNA that’s up to 11,400 years old from the floor of the much shallower Black Sea. The researchers say that the ability to retrieve such old DNA from such large stretches of the planet’s surface could help reveal everything from ancient climate to the evolutionary ecology of the seas.

“We have been able to show that the deep sea is the largest long-time archive of DNA, and a major window to study past biodiversity,” writes Pedro Martinez Arbizu, a deep-sea biologist of the German Centre for Marine Biodiversity Research in Wilhelmshaven and an author of the paper on South Atlantic DNA in an e-mail.

The new studies are “very exciting,” says micropaleontologist Bridget Wade of the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom, who was not connected to the research. Until now, it wasn’t clear “how far back in time you could take these DNA studies. … These records are telling you new information that wasn’t found in the fossil record.”

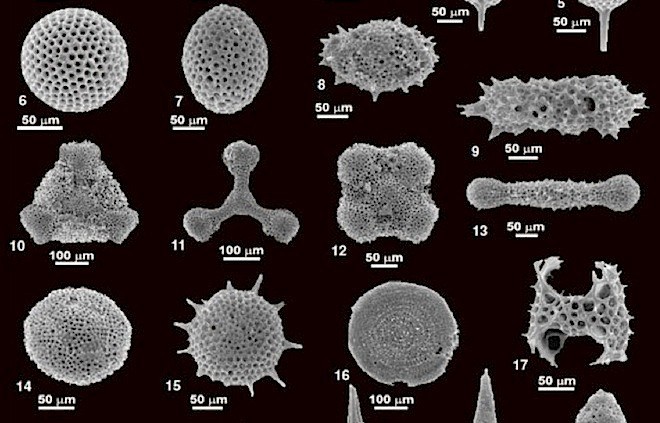

The South Atlantic team went looking for DNA in plugs of silt and clay coaxed out of the ocean floor hundreds of kilometers off the Brazilian coast. The researchers were after genetic material from two related groups of marine organisms, the foraminifera and the radiolarians. Both are single-celled, and both include many species with beautiful pearly shells that fossilize nicely, making them a favorite target of researchers studying the prehistoric oceans.

The researchers used special pieces of DNA specific to radiolarians and foraminifera to fish out DNA from those groups. Then they sequenced the DNA and compared the results to known foraminifera and radiolarian DNA sequences. Their analysis showed they’d found 169 foraminifera species and 21 radiolarian species, many of which were unknown. What’s more, many of the foraminifera species belonged to groups that don’t form fossils, the researchers report online today in Biology Letters.

The work shows that it’s possible to trace all species, not just those that fossilize, says Jan Pawlowski, a foraminifera specialist and one of the paper’s authors, of the University of Geneva in Switzerland. The results give “us a completely different view … [that] may open new insights into what’s happened in the past,” he says. For example, he says, different species of these wee creatures prefer different water temperatures. So DNA from buried sediments could be used to track the abundance of different species over time, revealing changes in ocean temperature.

The second team looked at DNA buried in the floor of the Black Sea, which was once a giant lake but became connected to the Mediterranean Sea roughly 9000 years ago, though the date is debated. The researchers examined sediments from waters only 980 meters deep, which is much shallower than the abyssal plain. But the oldest Black Sea layers that were analyzed were similar to those at the South Atlantic site: The mud at the sea bottom had scant amounts of organic matter and had been exposed to oxygen, which, in theory, should have made it tough to scrape up any preserved DNA.

It didn’t. New material had buried the older layers, cutting off their oxygen, and more recent Black Sea sediments weren’t exposed to oxygen at all. The result was a rich trove of ancient DNA from as many as 2700 species, including green algae, fungi, and dinoflagellates, a type of one-celled aquatic creature. The diverse collection allowed the scientists to track the fate of different species over time, as their DNA blinked in and out of the sediments.

One type of marine fungus, for example, first appeared in the sediments roughly 9600 years ago—exactly when some forms of freshwater plankton and a freshwater mussel vanish, the team reports this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. That suggests that marine waters started to invade the lake roughly 600 years earlier than thought. The team also found DNA from a form of marine alga in 9300-year-old sediments, though the alga doesn’t show up in the fossil record until 2500 years ago, says molecular paleoecologist Marco Coolen of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts and an author of the Black Sea paper.

Other ancient DNA studies have been discredited after supposedly ancient genetic material turned out to be modern contaminants, but those fears don’t apply to this new research, says micropaleontologist Michal Kucera of the University of Bremen in Germany. He says that both teams took the necessary steps to avoid contamination, and their results don’t look like contaminants. In the Biology Letters results, for instance, DNA from older sediments is more degraded than material from more recent sediment—not what you’d expect if the DNA were a laboratory stowaway.

Kucera and Wade praised both studies as paving the way for the use of ancient marine DNA to illuminate the history of the ocean. Coolen’s finding of marine species invading the Black Sea earlier than had been thought “is not something you could see from looking at fossils or sediment properties,” Kucera says.

Wade says that it may be possible, once researchers can identify the DNA of species that prefer certain environmental conditions, to use deep-water DNA to reveal changes in climate. “Most of the environment on Earth is marine deep ocean,” including the area where Pawlowski’s team found DNA, she says. “So it makes it very exciting that they’re looking in this environment and finding DNA.”

Story Source:

The above story is reprinted from materials provided by ScienceNOW. Photo: Minute fossil sea creatures recovered from sediments containing ancient DNA. Image: Lejzerowicz et al./Biology Letters