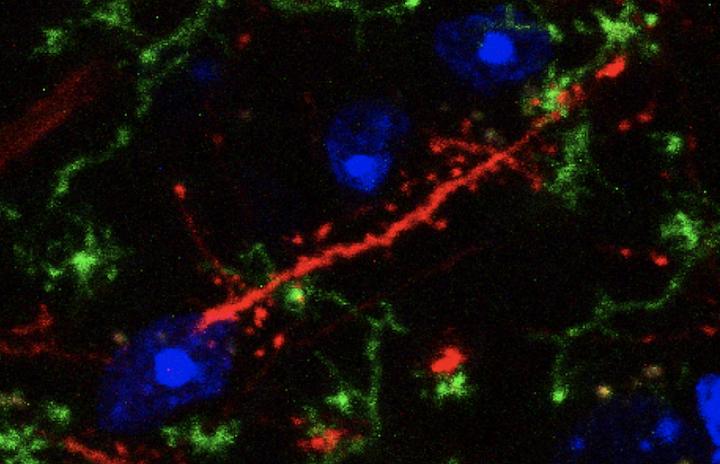

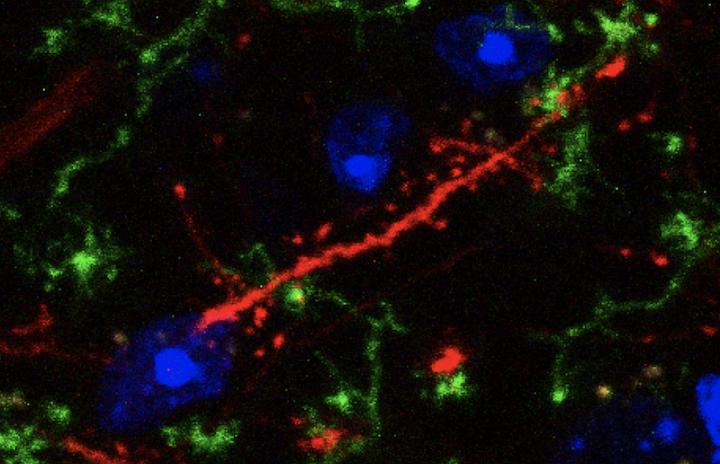

Credit: Boston Children's Hospital

Up to 75 percent of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus — an incurable autoimmune disease commonly known as lupus — experience neuropsychiatric symptoms. But so far, our understanding of the mechanisms underlying lupus' effects on the brain has remained murky. Now, new research from Boston Children's Hospital has shed light on the mystery and points to a potential new drug for protecting the brain from the neuropsychiatric effects of lupus and other central nervous system (CNS) diseases. The team has published its surprising findings in Nature.

"In general, lupus patients commonly have a broad range of neuropsychiatric symptoms, including anxiety, depression, headaches, seizures, even psychosis," says Allison Bialas, PhD, first author on the study and a research fellow working in the lab of Michael Carroll, PhD, senior author on the study, who are part of the Boston Children's Program in Cellular and Molecular Medicine. "But their cause has not been clear — for a long time it wasn't even appreciated that these were symptoms of the disease.

Collectively, lupus' neuropsychiatric symptoms are known as central nervous system (CNS) lupus. Carroll's team wondered if changes in the immune system in lupus patients were directly causing these symptoms from a pathological standpoint.

"How does chronic inflammation affect the brain?"

Lupus, which affects at least 1.5 million Americans, causes the immune systems to attack the body's tissues and organs. This causes the body's white blood cells to release type 1 interferon-alpha, a small cytokine protein that acts as a systemic alarm, triggering a cascade of additional immune activity as it binds with receptors in different tissues.

Until now, however, these circulating cytokines were not thought to be able to cross the blood brain barrier, the highly-selective membrane that controls the transfer of materials between circulating blood and the central nervous system (CNS) fluids.

"There had not been any indication that type 1 interferon could get into the brain and set off immune responses there," says Carroll, who is also professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School.

So, working with a mouse model of lupus, it was quite unexpected when Carroll's team discovered that enough interferon-alpha did indeed appear to permeate the blood brain barrier to cause changes in the brain. Once across the barrier, it launched microglia — the immune defense cells of the CNS — into attack mode on the brain's neuronal synapses. This caused synapses to be lost in the frontal cortex.

"We've found a mechanism that directly links inflammation to mental illness," says Carroll. "This discovery has huge implications for a range of central nervous system diseases."

Blocking inflammation's effects on the brain

The team decided to see if they could reduce synapse loss by administering a drug that blocks interferon-alpha's receptor, called an anti-IFNAR.

Remarkably, they found that anti-IFNAR did seem to have neuro-protective effects in mice with lupus, preventing synapse loss when compared with mice who were not given the drug. What's more, they noticed that mice treated with anti-IFNAR had a reduction in behavioral signs associated with mental illnesses such as anxiety and cognitive defects.

Although further study is needed to determine exactly how interferon-alpha is crossing the blood brain barrier, the team's findings establish a basis for future clinical trials to investigate the effects of anti-IFNAR drugs on CNS lupus and other CNS diseases. One such anti-IFNAR, anifrolumab, is currently being evaluated in a phase 3 human clinical trial for treating other aspects of lupus.

"We've seen microglia dysfunction in other diseases like schizophrenia, and so now this allows us to connect lupus to other CNS diseases," says Bialas. "CNS lupus is not just an undefined cluster of neuropsychiatric symptoms, it's a real disease of the brain — and it's something that we can potentially treat."

The implications go beyond lupus because inflammation underpins so many diseases and conditions, ranging from Alzheimer's to viral infection to chronic stress.

"Are we all losing synapses, to some varying degree?" Carroll suggests. His team plans to find out.

###

This research was supported by the Alliance for Lupus Research (ALR – 332527); the NIH (AI039246, AI42269, AI74549); MedImmune LLC; and the Jeffrey Modell Foundation. In addition to Bialas and Carroll, other authors on the paper included: Jessy Presumey, Abhishek Das, Cornelis van der Poel, Peter H. Lapchak, Luka Mesin, Gabriel Victora, George C. Tsokos, Christian Mawrin and Ronald Herbst.

About Boston Children's Hospital

Boston Children's Hospital, the primary pediatric teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School, is home to the world's largest research enterprise based at a pediatric medical center. Its discoveries have benefited both children and adults since 1869. Today, more than 2,630 scientists, including nine members of the National Academy of Sciences, 14 members of the National Academy of Medicine and 11 Howard Hughes Medical Investigators comprise Boston Children's research community. Founded as a 20-bed hospital for children, Boston Children's is now a 415-bed comprehensive center for pediatric and adolescent health care. For more, visit our Vector and Thriving blogs and follow us on social media @BostonChildrens,@BCH_Innovation, Facebook and YouTube.

Media Contact

Bethany Tripp

[email protected]

@BostonChildrens

http://www.childrenshospital.org/newsroom

############

Story Source: Materials provided by Scienmag