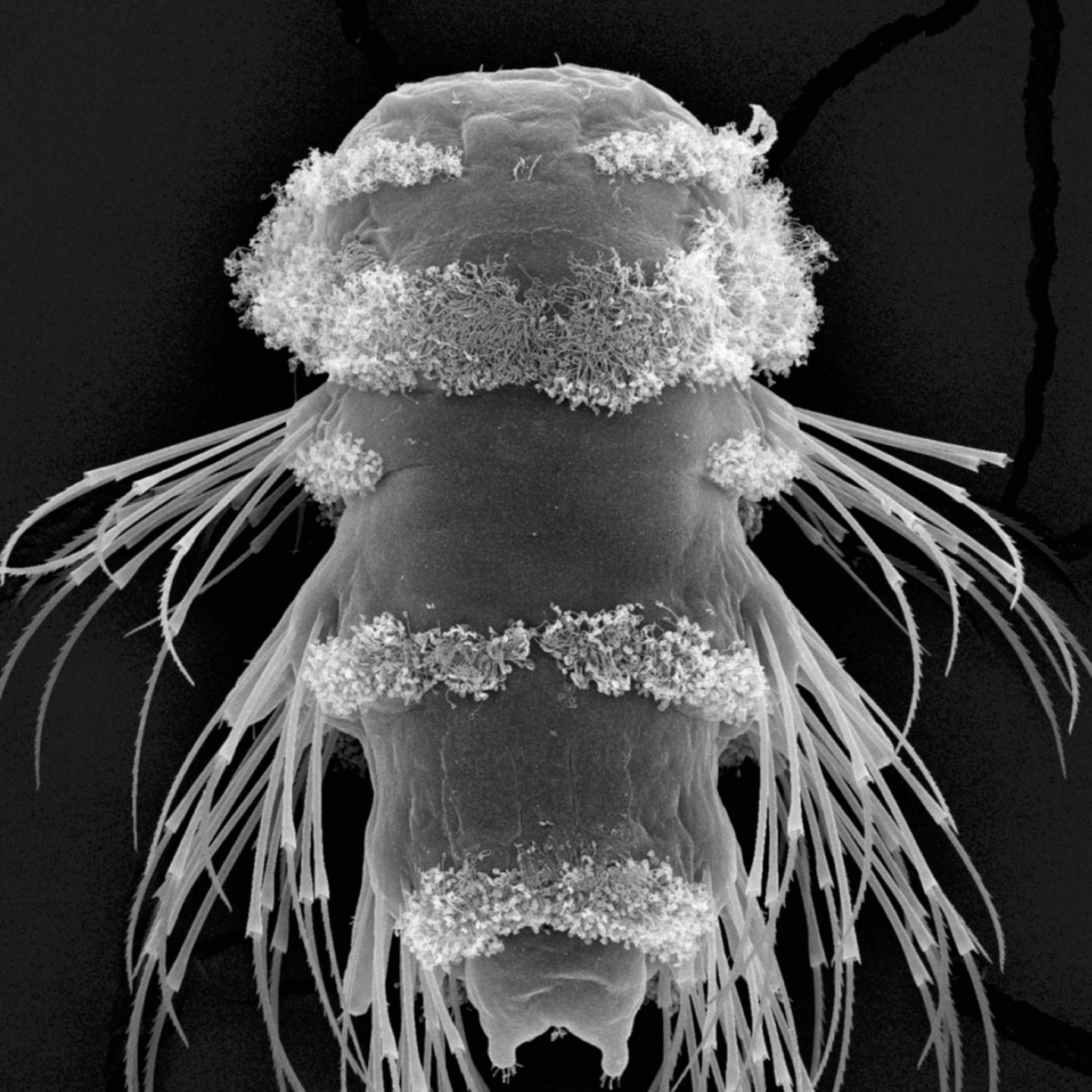

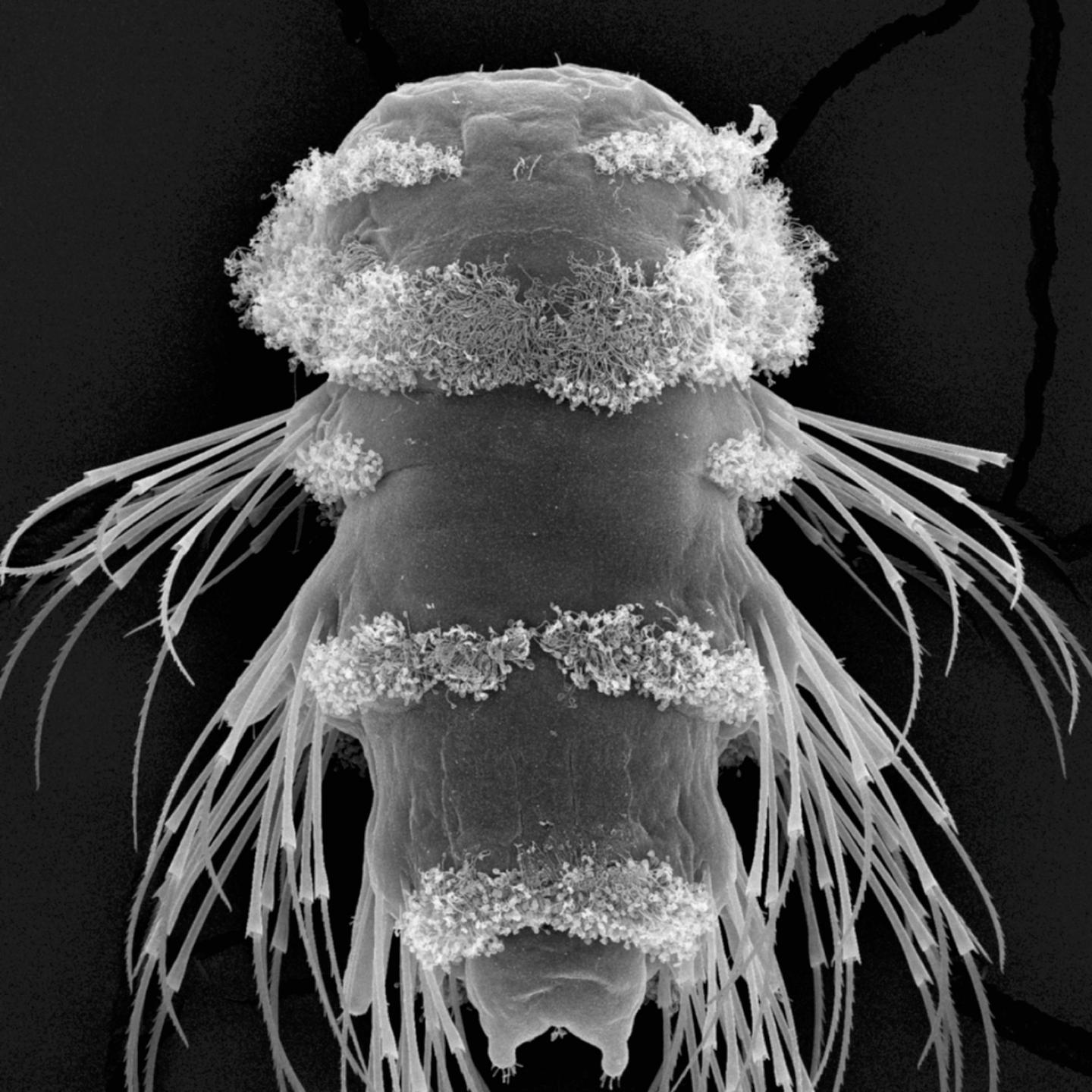

Credit: Jürgen Berger

The eyes of some marine-dwell

The eyes of some marine-dwelling creatures have evolved to act like a "depth gauge", allowing these creatures to swim in the open ocean at a certain depth .

Pioneering new research, carried out by a team of international scientists including Professor Gaspar Jekely from the University of Exeter, has shed new light on how sea-living planktonic animals use their simple eyes to measure depth in the ocean.

All eyes detect light using specialized cells called photoreceptors, of which there are two main kinds: ciliary and rhabdomeric. While crustaceans and insects have rhabdomeric photoreceptors, animals with backbones – including humans – have ciliary photoreceptors.

However, there are also several groups of animals, mostly sea-dwellers, which inherited both types of photoreceptors from their ancestors that lived millions of years ago.

The new research, carried out by experts from Exeter's Living Systems Institute and collaborators at the University of Vienna and Emory University, has given a greater understanding of how the two kinds of photoreceptors interact in such a sea dweller, shedding new light on the evolution of eyes and photoreceptors.

The researchers studied the larvae of the marine ragworm, Platynereis dumerilii. The larvae of Platynereis are free-swimming plankton. Each has a transparent brain and six small, pigmented eyes which contain rhabdomeric photoreceptors . These enable the larvae to detect and swim towards light sources. Yet the larval brain also contains ciliary photoreceptors, the role of which was previously unknown.

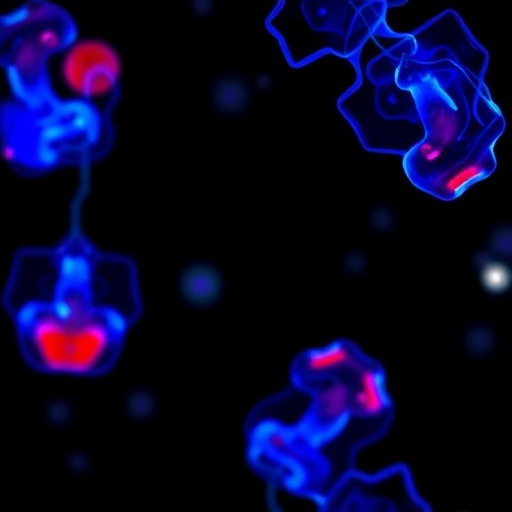

The new research has revealed that ultraviolet light activates these ciliary photoreceptors, whereas cyan, or blue-green light inhibits them. Shining ultraviolet light onto Platynereis larvae makes the larvae swim downwards. By contrast, cyan light activates the rhabdomeric pigmented eyes and makes the larvae swim upwards.

In the ocean, ultraviolet light is most intense near the surface, while cyan light reaches greater depths. Ciliary photoreceptors are therefore shown to help Platynereis avoid harmful ultraviolet radiation near the surface. Though if the larvae swim too deep, cyan light inhibits the ciliary photoreceptors and activates the rhabdomeric pigmented eyes. This makes the larvae swim upwards again.

The research team also used high-powered electron microscopy to show that the neural circuits containing ciliary photoreceptors exchange messages with circuits containing rhabdomeric photoreceptors – suggesting the two work together to form a 'depth gauge'.

By enabling the larvae to swim at a preferred depth, the depth gauge influences where the worms end up as adults.

Professor Gaspar Jekely, from Exeter's Living Systems Institute said: "The idea that marine animals could use light to estimate their depth has already been proposed by theoretician, but to our knowledge this is the first time that such a mechanism has been experimentally studied."

Csaba Verasztó, one of the first authors of the study added: "Detecting different types of light with different photoreceptor cells in marine plankton may have been the ancestral framework for light detection in animals."

The depth gauge in Platynereis larvae represents an important new mechanism to influence the distribution of marine animals. Its discovery should also stimulate new ideas about the evolution of eyes and photoreceptors.

Ciliary and rhabdomeric photoreceptor-cell circuits form a spectral depth gauge in marine zooplankton is published in the journal eLife.

###

ing creatures have evolved to act like a "depth gauge", allowing these creatures to swim in the open ocean at a certain depth .

Pioneering new research, carried out by a team of international scientists including Professor Gaspar Jekely from the University of Exeter, has shed new light on how sea-living planktonic animals use their simple eyes to measure depth in the ocean.

All eyes detect light using specialized cells called photoreceptors, of which there are two main kinds: ciliary and rhabdomeric. While crustaceans and insects have rhabdomeric photoreceptors, animals with backbones – including humans – have ciliary photoreceptors.

However, there are also several groups of animals, mostly sea-dwellers, which inherited both types of photoreceptors from their ancestors that lived millions of years ago.

The new research, carried out by experts from Exeter's Living Systems Institute and collaborators at the University of Vienna and Emory University, has given a greater understanding of how the two kinds of photoreceptors interact in such a sea dweller, shedding new light on the evolution of eyes and photoreceptors.

The researchers studied the larvae of the marine ragworm, Platynereis dumerilii. The larvae of Platynereis are free-swimming plankton. Each has a transparent brain and six small, pigmented eyes which contain rhabdomeric photoreceptors . These enable the larvae to detect and swim towards light sources. Yet the larval brain also contains ciliary photoreceptors, the role of which was previously unknown.

The new research has revealed that ultraviolet light activates these ciliary photoreceptors, whereas cyan, or blue-green light inhibits them. Shining ultraviolet light onto Platynereis larvae makes the larvae swim downwards. By contrast, cyan light activates the rhabdomeric pigmented eyes and makes the larvae swim upwards.

In the ocean, ultraviolet light is most intense near the surface, while cyan light reaches greater depths. Ciliary photoreceptors are therefore shown to help Platynereis avoid harmful ultraviolet radiation near the surface. Though if the larvae swim too deep, cyan light inhibits the ciliary photoreceptors and activates the rhabdomeric pigmented eyes. This makes the larvae swim upwards again.

The research team also used high-powered electron microscopy to show that the neural circuits containing ciliary photoreceptors exchange messages with circuits containing rhabdomeric photoreceptors – suggesting the two work together to form a 'depth gauge'.

By enabling the larvae to swim at a preferred depth, the depth gauge influences where the worms end up as adults.

Professor Gaspar Jekely, from Exeter's Living Systems Institute said: "The idea that marine animals could use light to estimate their depth has already been proposed by theoretician, but to our knowledge this is the first time that such a mechanism has been experimentally studied."

Csaba Verasztó, one of the first authors of the study added: "Detecting different types of light with different photoreceptor cells in marine plankton may have been the ancestral framework for light detection in animals."

The depth gauge in Platynereis larvae represents an important new mechanism to influence the distribution of marine animals. Its discovery should also stimulate new ideas about the evolution of eyes and photoreceptors.

Ciliary and rhabdomeric photoreceptor-cell circuits form a spectral depth gauge in marine zooplankton is published in the journal Elife.

###

Media Contact

Duncan Sandes

[email protected]

44-013-927-22391

@uniofexeter

http://www.exeter.ac.uk

Related Journal Article

http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.36440