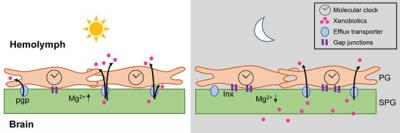

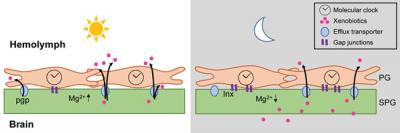

Credit: The lab of Amita Sehgal, PhD, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania

PHILADELPHIA – The blood brain barrier (BBB), like a bouncer outside an exclusive night club, stands guard between the brain and the rest of the body. The barrier consists of tight junctions between cells lining blood vessels to keep harmful toxins and germs out of the brain. But this can also bar entry to many medications used to treat brain illnesses.

This week in Cell, a study led by Amita Sehgal, PhD, a professor of Neuroscience in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, describes that the permeability of the fruit fly version of the barrier is higher at night versus during the day. In addition, her team found that this daily rhythm is governed by a molecular clock in the support cells within the barrier, which affected how mutant flies responded to an anti-epileptic drug. The study's first author is Shirley Zhang, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Sehgal's lab.

A key obstacle for development of drugs to treat brain and central nervous system diseases is designing a means of efficient passage through the BBB. Higher doses can help, but that strategy carries a risk to other organs.

"There have been hints in past studies that the opening of the blood brain barrier fluctuates over 24 hours and now we see, for the first time, direct evidence that a local circadian clock exists in the barrier," Sehgal said. "More importantly, we have identified a novel daily regulation that could have implications for the timing of taking medications targeted to the central nervous system."

Using a dye, her team showed that transmitting clock signals across the BBB requires gap junctions, which are expressed cyclically. These are protein complexes organized into channels in cell membranes that allow ions and small molecules to pass between cells. Specifically, during the night, magnesium passes through the junctions to decrease its concentration in cells that form the tight barrier, therefore allowing substances to permeate the brain.

To test if the cyclical permeability might also lead to a better outcome if brain drugs are administered at night, they gave mutant flies prone to seizures the anti-epileptic phenytoin. While the incidence of seizures did not vary over the course of the day-night cycle, flies given the drug at night had a shorter time to recovery after seizures compared to flies given phenytoin during the day.

Those findings suggest that timing the delivery of drugs that act in the brain should consider when the barrier is open as well as other cyclical aspects of neuron physiology. One relevant line of research is to identify the drugs most likely to be targeted by the mechanism that drives a rhythm in BBB permeability

###

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (T32HL07713 and R37NS048471) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $7.8 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine has been ranked among the top five medical schools in the United States for the past 20 years, according to U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $405 million awarded in the 2017 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and Penn Presbyterian Medical Center — which are recognized as one of the nation's top "Honor Roll" hospitals by U.S. News & World Report — Chester County Hospital; Lancaster General Health; Penn Medicine Princeton Health; Penn Wissahickon Hospice; and Pennsylvania Hospital – the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Additional affiliated inpatient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region include Good Shepherd Penn Partners, a partnership between Good Shepherd Rehabilitation Network and Penn Medicine, and Princeton House Behavioral Health, a leading provider of highly skilled and compassionate behavioral healthcare.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2017, Penn Medicine provided $500 million to benefit our community.

Media Contact

Karen Kreeger

[email protected]

215-459-0544

@PennMedNews

http://www.uphs.upenn.edu/news/