Credit: University of Iowa

Mothers contribute a lot of defining traits to their offspring, from eye color to toe length. But pregnant mothers with health complications, such as diabetes or hypertension, also can pass these symptoms to their children.

What if we could prevent that?

In a new study, researchers at the University of Iowa have shown they can reverse high blood pressure in offspring born to hypertensive rats. The results, though preliminary, may offer a promising avenue toward addressing "fetal programming," or the in utero transfer of certain health risks from mothers to children.

The findings were published online this week in the journal Hypertension.

In humans, gestational hypertension affects up to 15 percent of pregnancies. That percentage may rise because high blood pressure generally increases as we age, and American women are waiting longer to have children. Moreover, multiple studies have documented that offspring born to hypertensive mothers have higher blood pressure in childhood and are at higher risk of being hypertensive and contracting heart disease as adults.

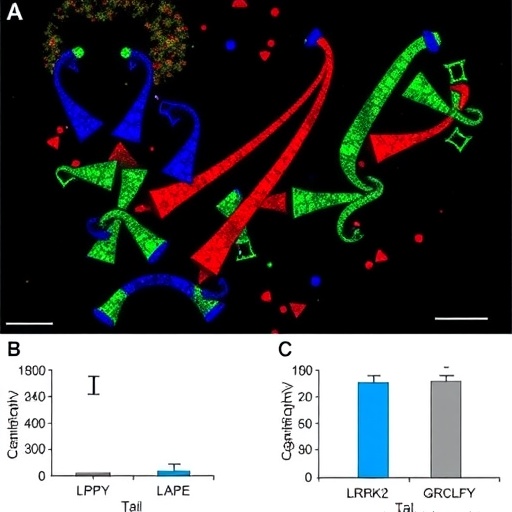

UI professor Alan Kim Johnson and his colleagues wanted to understand if gestational hypertension would affect blood pressure in baby rats and, if so, how the rats' brains might be involved. The group induced hypertension in mother rats during the perinatal period (three weeks before and after birth) and measured the blood pressure response in the offspring at 10 weeks, the rat equivalent of adulthood. The offspring were then given a hormone that elevates blood pressure to determine how they would respond.

"What you see is enhanced, that is, a sensitized hypertensive response in animals where mothers had been hypertensive during pregnancy," says Johnson, F. Wendell Miller Distinguished Professor in the UI's Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences.

The researchers then administered a drug called Captopril, which is commonly used to treat high blood pressure in human adults, to the rats born to hypertensive mothers and that had also been given the blood-pressure hormone. The rats that received Captopril from three to nine weeks of age were then tested for hypertension at 10 weeks and showed no signs of enhanced high blood pressure.

"That means we can, in effect, deprogram them," Johnson says.

Whether this would translate to humans is far from clear. But it opens a path for further study of the neural and chemical changes that occur in the brains of offspring born to hypertensive mothers–or mothers with other health issues–and how those conditions ultimately are passed on.

Johnson's team has begun to document that transfer by tracking how the brain and central nervous system react to high blood pressure stressors. One, caused by a hormone called angiotensin II, appears to activate pathways from the brain that trigger a "sympathetic" response from the central nervous system. In other words, the central nervous system becomes more prone to elevate blood pressure when it senses the hormone. Researchers hypothesize the sympathetic response may become more conditioned, or overly responsive, in humans due to natural causes, such as with the children of mothers who had high blood pressure during their pregnancy.

Johnson compares the process to a memory being made. In this case, the brain is establishing a "memory" of high blood pressure that's passed on to the offspring. But, importantly, researchers showed in the rat experiments that the memory can be altered, even erased.

"We've changed the information that was laid down in the brain," Johnson says.

###

"This study on rats sheds some light on how maternal health during pregnancy impacts long-term cardiovascular health of the offspring, says Christine Maric-Bilkan, program officer of the Division of Cardiovascular Sciences of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI). "These findings suggest a potential therapeutic strategy for prevention of elevated blood pressure in adults who were born to mothers that themselves had elevated blood pressure during pregnancy."

Baojian Xue, in the UI Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences at the UI, is the first author. Contributing authors, also with the psychological and brain sciences department, are Fang Guo, Terry Beltz, and Robert Thunhorst. Haifeng Yin, a visiting professor now at Hebei North University in China, also contributed to the research. Johnson also is affiliated with the UI's pharmacology program and the Francois Abboud Cardiovascular Research Center.

The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, part of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, funded the research through grants to Johnson.

Media Contact

Richard Lewis

[email protected]

319-384-0012

@uiowa

http://www.uiowa.edu