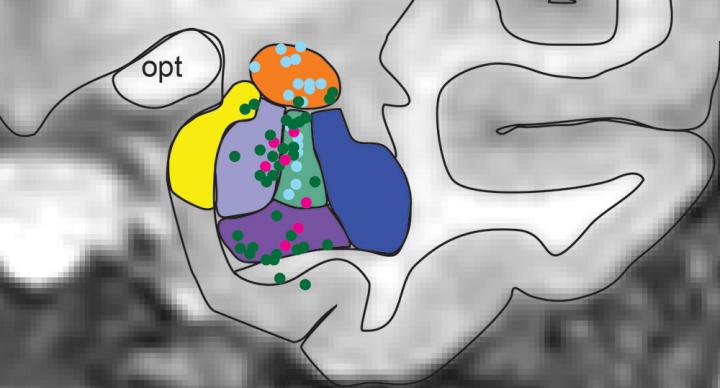

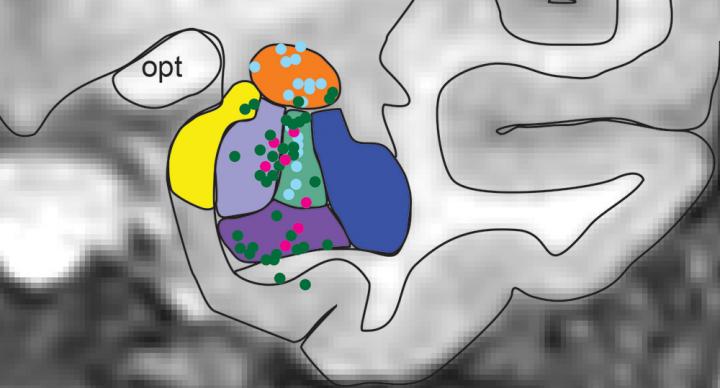

Credit: J. Minxha/Adolphs lab

When we are walking down a crowded street, our brains are constantly active, processing a myriad of visual stimuli. Faces are particularly important social stimuli, and, indeed, the human brain has networks of neurons dedicated to processing faces. These cells process social information such as whether individual faces in the crowd are happy, threatening, familiar, or novel.

New research from Caltech now shows that the activation of face cells depends highly on where you are paying attention–it is not enough for a face to simply be within your field of vision. The findings may lead to a better understanding of the mechanisms behind social cognitive defects that characterize conditions such as autism.

The research was conducted in the laboratories of Ralph Adolphs (PhD '93), Bren Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience and professor of biology, and collaborator Ueli Rutishauser (PhD '08) of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles and a visiting associate in biology and biological engineering at Caltech.

A paper about the work appears in the January 24 issue of Cell Reports.

"The ability to recognize other human faces is the basis of social awareness and interaction," Adolphs says. "Previous work on this subject has typically been conducted under rather artificial conditions–a single, large image is displayed on a monitor in front of a subject to focus on. We wanted to understand how brain activity changes with eye movements and capture the natural dynamics of how people constantly shift their attention in crowded scenes."

The researchers focused on face cells in a particular region of the brain called the amygdala.

"We know that a damaged amygdala can result in profound deficits in face processing, especially in recognizing emotions, but how amygdala neurons normally contribute to face perception is still a big open question," says Juri Minxha, a graduate student in Caltech's computation and neural systems program and lead author on the paper. "Now, we have discovered that face cells in the amygdala respond differently depending on where the subject is fixating."

When a face cell responds to a stimulus, it fires electrical impulses or "spikes." By working with patients who already had electrodes implanted within their amygdalae for clinical reasons, the group measured the activity of individual face cells while simultaneously monitoring where a subject looked. Subjects were shown images of human faces, monkey faces, and a variety of other objects such as flowers and shapes. This study is the first in which subjects were free to look around at various parts of a screen and focus their attention on different things.

The study found two types of face cells: those that fire more spikes when the patient is looking at a human face and those that fire a few spikes when the patient is looking at a face of another species (in this case, that of a monkey). Neither type of face cell fired when the subjects were paying attention to objects that were not faces, even if those objects were near a face in the image.

"We saw that if a person was paying attention to a flower picture, for example, the face cells would not fire even if the flower was close to a face," says senior author Rutishauser. "This suggests that the responses of face cells are controlled by where we are focusing our attention."

Experiments in monkeys, performed in collaboration with Katalin Gothard of the University of Arizona, showed similar results. In both groups of subjects, face cells were most responsive to conspecifics–faces of the same species. "This is remarkable because many aspects of social perception and social behavior are different between the two species," Gothard says. "This discovery now indicates that the primate amygdala is an integral part of the network of brain areas dedicated to processing the faces we pay attention to, and is the first such direct comparison between humans and monkeys."

The studies showed that when the monkey and human subjects were viewing images of the same species, the monkeys' face cells reacted about one-tenth of a second more quickly than the face cells of humans, validating a long-standing hypothesis that face cells in monkeys would respond more quickly than corresponding cells in humans. The tenth-of-a-second difference is larger than what can be explained by variation in human and monkey brain size, leaving open the question of why human face cells have a delayed response. "The power of this comparative approach is that it identifies critical differences in brain function that might be unique to humans," Rutishauser says.

"The experimental design brings researchers a step closer to studying how the brain works during natural behaviors," Minxha says. "Ideally, we would want to observe neural activity while a person actually moves through a crowded scene. The next step is to study how face-cell activation changes with the subject's emotional state, or when they are interacting with someone. We would also like to understand how face-cell responses are different in subjects with specific clinical disorders, such as in people with autism, which is work we have been conducting as well."

###

The paper is titled "Fixations gate species-specific responses to free viewing of faces in the human and macaque amygdala." Other co-authors include Clayton Mosher and Jeremiah Morrow of the University of Arizona and Adam Mamelak of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. The work was funded by the National Science Foundation, the National Institute of Mental Health, the McKnight Endowment Fund for Neuroscience, and a NARSAD Young Investigator Award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation.

Media Contact

Lori Dajose

[email protected]

626-658-0109

@caltech

http://www.caltech.edu