For detecting cancer, manual breast exams seem low-tech compared to other methods such as MRI. But scientists are now developing an “electronic skin” that “feels” and images small lumps that fingers can miss. Knowing the size and shape of a lump could allow for earlier identification of breast cancer, which could save lives. They describe their device, which they’ve tested on a breast model made of silicone, in the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

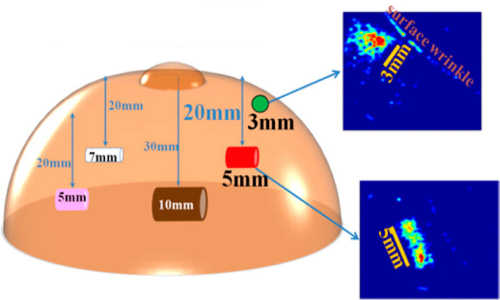

Using a silicone model of a breast and embedding objects representing lumps, scientists have successfully tested an electronic skin that can accurately “feel” and image lumps much smaller than those detectable by manual exams. Photo Credit:American Chemical Society

Ravi F. Saraf and Chieu Van Nguyen point out that early diagnosis of breast cancer, the most common type of cancer among women, can help save lives. But small masses of cancer cells are not always easy to catch. Current testing methods, including MRI and ultrasounds, are sensitive but expensive. Mammography is imperfect, especially when it comes to testing young women or women with dense breast tissue. Clinical breast exams performed by medical professionals as an initial screening step are inexpensive, but typically don’t find lumps until they’re 21 millimeters in length, which is about four-fifths of an inch. Detecting lumps and determining their shape when they’re less than half that size improves a patient’s survival rate by more than 94 percent. Some devices already mimic a manual exam, but their image quality is poor, and they cannot determine a lump’s shape, which helps doctors figure out whether a tumor is cancerous. Saraf and Nguyen wanted to fill this gap.

Toward that end, they made a kind of electronic skin out of nanoparticles and polymers that can detect, “feel” and image small objects. To test how it might work on a human patient, they embedded lump-like objects in a piece of silicone mimicking a breast and pressed the device against this model with the same pressure a clinician would use in a manual exam. They were able to image the lump stand-ins, which were as little as 5 mm and as deep as 20 mm. Saraf says the device could also be used to screen patients for early signs of melanoma and other cancers.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by American Chemical Society.