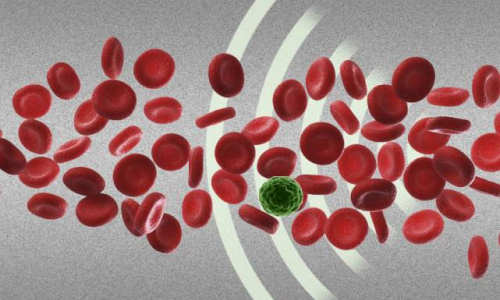

Acoustic device that separates tumor cells from blood cells could help assess cancer’s spread.

Photo Credit: Illustration Christine Daniloff/MIT

Researchers from MIT, Pennsylvania State University, and Carnegie Mellon University have devised a new way to separate cells by exposing them to sound waves as they flow through a tiny channel. Their device, about the size of a dime, could be used to detect the extremely rare tumor cells that circulate in cancer patients’ blood, helping doctors predict whether a tumor is going to spread.

Separating cells with sound offers a gentler alternative to existing cell-sorting technologies, which require tagging the cells with chemicals or exposing them to stronger mechanical forces that may damage them.

“Acoustic pressure is very mild and much smaller in terms of forces and disturbance to the cell. This is a most gentle way to separate cells, and there’s no artificial labeling necessary,” says Ming Dao, a principal research scientist in MIT’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering and one of the senior authors of the paper, which appears this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Subra Suresh, president of Carnegie Mellon, the Vannevar Bush Professor of Engineering Emeritus, and a former dean of engineering at MIT, and Tony Jun Huang, a professor of engineering science and mechanics at Penn State, are also senior authors of the paper. Lead authors are MIT postdoc Xiaoyun Ding and Zhangli Peng, a former MIT postdoc who is now an assistant professor at the University of Notre Dame.

The researchers have filed for a patent on the device, the technology of which they have demonstrated can be used to separate rare circulating cancer cells from white blood cells.

To sort cells using sound waves, scientists have previously built microfluidic devices with two acoustic transducers, which produce sound waves on either side of a microchannel. When the two waves meet, they combine to form a standing wave (a wave that remains in constant position). This wave produces a pressure node, or line of low pressure, running parallel to the direction of cell flow. Cells that encounter this node are pushed to the side of the channel; the distance of cell movement depends on their size and other properties such as compressibility.

However, these existing devices are inefficient: Because there is only one pressure node, cells can be pushed aside only short distances.

The new device overcomes that obstacle by tilting the sound waves so they run across the microchannel at an angle — meaning that each cell encounters several pressure nodes as it flows through the channel. Each time it encounters a node, the pressure guides the cell a little further off center, making it easier to capture cells of different sizes by the time they reach the end of the channel.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Anne Trafton.