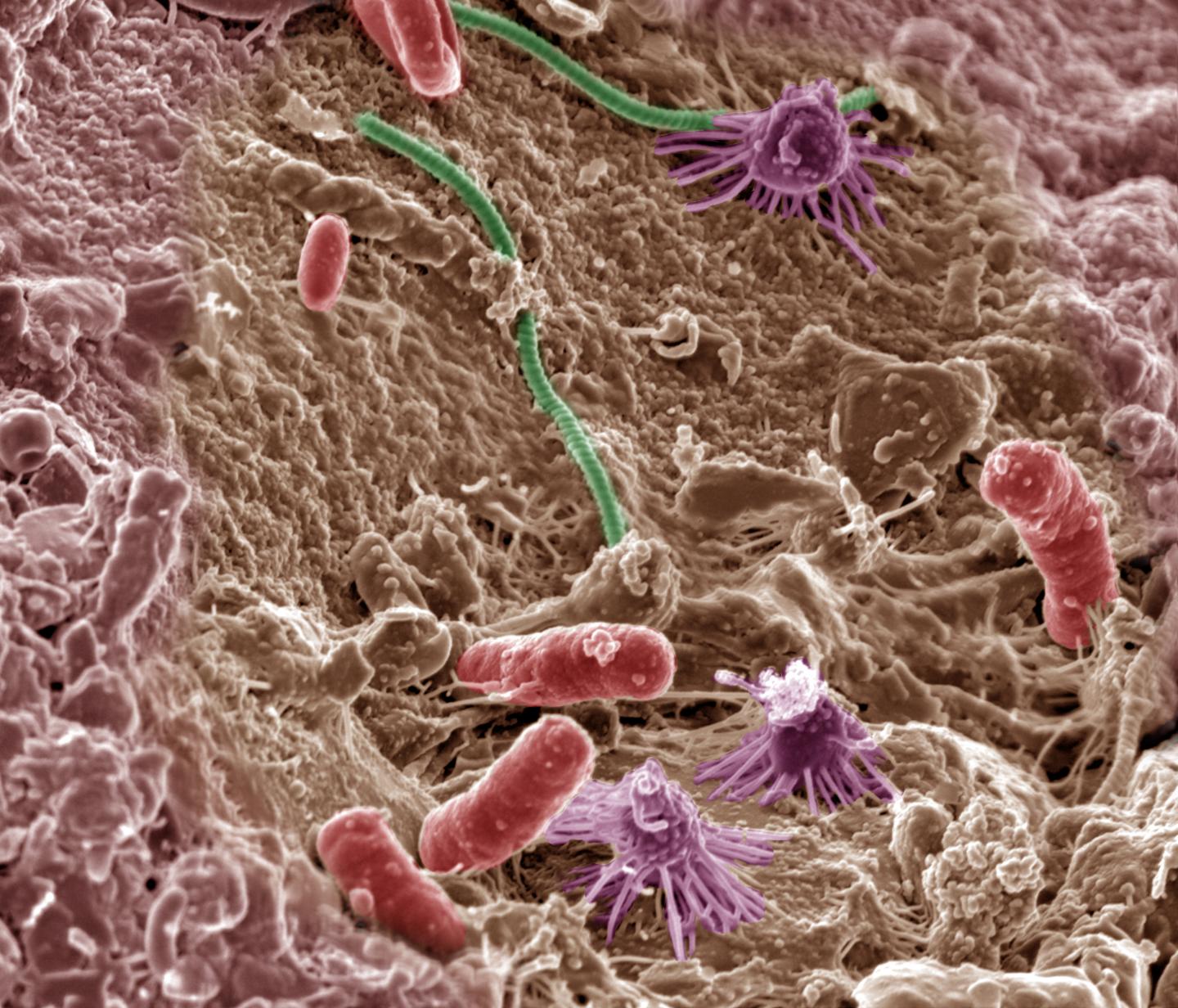

Credit: Courtesy of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

AUSTIN, Texas – Scientists have known that microbes living in the ground can play a major role in producing atmospheric carbon that can accelerate climate change, but now researchers from The University of Texas at Austin have discovered that soil microbes from historically wetter sites are more sensitive to moisture and emit significantly more carbon than microbes from historically drier regions. The findings, reported today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, point the way toward more accurate climate modeling and improve scientists' understanding of distinct regional differences in microbial life.

Microbes in the soil add between 44 billion and 77 billion tons of carbon to the atmosphere each year — more than all fossil fuels combined — through a process called respiration. As the planet warms, soil respiration is expected to increase, but forecasters have had trouble accurately pinpointing by how much. The new research indicates that to do a better job of predicting changes in soil respiration, forecasters need to pay attention not only to climate change but also to climate history, as microbes respond differently to shifts in their environment in wetter versus drier areas.

In regions with more rainfall historically, soil microbes were found to respire twice as much carbon to the atmosphere as microbes from drier regions. Scientists determined that this was because the microbes responded differently to change: Those from the wettest areas were four times as sensitive to shifts in moisture as their counterparts from the driest areas.

"Current models assume that soil microbes at any site around the world exhibit the same responses to environmental change and do so instantaneously," says Christine Hawkes, a professor of integrative biology, "but we demonstrated that historical rainfall shapes the soil respiration response."

It is unclear whether the insight into how soil microbes respond to moisture would drastically change the results of worldwide climate modeling efforts, which, so far, have taken different approaches to estimating how soil respiration responds to moisture. Incorporating the new discovery into ecosystem models, however, could help improve predictions based on local or regional differences in soil respiration and climate history.

Hawkes and the team conducted three long-term studies involving field research and lab experiments occurring over six years. In each case, the finding was the same: Historical rainfall levels proved critical for how soil microbes would respond to change, affecting the outcome just as temperature does.

"You've heard of the crisis of replication? Well, we tested this three different ways, and we couldn't get the soils to do anything different," Hawkes says. "This suggests that rainfall legacies will constrain future soil function, but we need further study to figure out by how much and for how long."

The research also highlights previously unknown nuances about the communities of microbes living under ground. Simple and microscopic, microbes nonetheless possess distinctive traits. Through decomposition and respiration, soil microbes affect the balance between carbon trapped under ground and emitted into the atmosphere, and this balance is not the same from one regional community to the next, the UT Austin researchers learned. They examined soil collected at various spots in Texas along the Edwards Plateau and found that microbes from the driest soil samples (living in areas with one-quarter as much water as the microbes from the wettest soils) responded with a fraction of the carbon emissions their wet-soil cousins produced. These differences persisted regardless of other soil characteristics.

"Because microbes are small and enormously diverse, we have this idea that when the environment changes, microbes can rapidly move around or shift local abundances to track that environmental change," Hawkes said. "We discovered, however, that soil microbes and their functions are highly resistant to change. Resistance to environmental change matters because it means that previous local conditions will constrain how ecosystems function when faced with a shift in climate."

###

The paper's co-authors include two former graduate students of Hawkes' — Bonnie Waring, now at Utah State University; and Jennifer Rocca, currently at Duke University — as well as a former postdoctoral researcher, Stephanie Kivlin, now at the University of New Mexico and beginning at the University of Tennessee in January.

Support for the study was provided by the Department of Energy's National Institute for Climate Change Research and Texas Ecolab.

Media Contact

Christine Sinatra

[email protected]

512-471-4641

@UTAustin

http://www.utexas.edu

############

Story Source: Materials provided by Scienmag