Urban landscapes, often viewed primarily as sprawling human habitats, have increasingly been recognized as critical arenas for ecological dynamics. Until recently, the science of urban ecology largely hinged on localized studies involving single cities, thereby constraining a comprehensive understanding of how urban environments interact with natural processes on a continental or global scale. However, a groundbreaking study published in Nature Cities is shattering these limitations by leveraging radar remote sensing to map migratory bird stopover patterns across 2,130 parks spanning 88 urban areas throughout the continental United States. This expansive approach sheds new light on the multifaceted role cities play in migratory bird ecology and reveals intricate links between avian stopover behavior, urbanization, and social landscapes.

At the core of this study is the use of advanced radar technology that tracks migratory birds as they pause during their long-distance journeys. Unlike traditional field observations, radar provides a vast coverage area and continuous data capture, allowing researchers to detect patterns at aerosol scale. This proves crucial in urban ecology, where habitat patches are unevenly distributed, and bird behavior can be influenced by a host of anthropogenic factors. By analyzing radar-derived data on the density and distribution of migratory birds stopping over in metropolitan parks, the research team has unveiled that urban areas, which cover a fraction of the land, disproportionately serve as stopover hotspots. Nearly half of detected migratory bird stopovers during both spring (48%) and fall (44%) seasons occur within Metropolitan Statistical Areas.

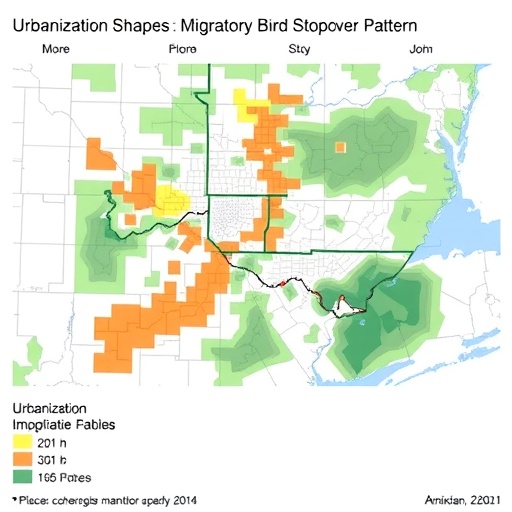

The implications of these findings are profound. First, they challenge the long-held notion that urbanization is invariably detrimental to migratory bird populations. Instead, cities can offer essential resting habitats that contribute meaningfully to the birds’ migratory success. However, this relationship is far from uniform across the continent. The study reveals a striking east-west dichotomy in how urbanization correlates with stopover use. Along the Eastern Flyways, higher urbanization levels tend to be associated with reduced stopover activity, suggesting that urban sprawl here might pose challenges such as habitat fragmentation or light pollution, which disorient birds or degrade habitat quality. Conversely, in Western Flyways, urban areas appear to offer more favorable conditions for stopover, with rising urbanization correlating positively with stopover density.

This regional variation emphasizes the necessity of adopting scale-sensitive and context-aware frameworks within urban ecology. Factors such as geographic location, urban planning practices, and local environmental policies may either mitigate or exacerbate the habitat quality for migratory birds. The heterogeneous nature of urban landscapes—comprising parks, green roofs, vacant lots, and water bodies—might partly explain the disparate stopover patterns observed across cities. Moreover, the research delves deeper into the socio-demographic dimensions linked with urban ecological patterns. Intriguingly, a positive correlation was found between migratory bird stopover frequency and household income in many urban areas. This association could stem from the fact that wealthier neighborhoods often contain better-maintained green spaces, greater tree canopy cover, and more biodiversity-friendly urban designs.

Nonetheless, the relationship between income levels and bird stopover abundance is not absolute. Some cities exhibit weak or even inverse correlations, underscoring that socio-economic factors intersect in complex ways with ecological phenomena. These findings open new lines of inquiry into how urban environmental justice and socio-political dynamics affect biodiversity conservation. Understanding these links is crucial, as disparities in access to quality green spaces can have broader implications not only for wildlife but also for human wellbeing, particularly in rapidly urbanizing regions.

The methodological innovation in this study—a large-scale application of radar remote sensing combined with socio-demographic datasets—represents a leap forward in the ability to probe urban biodiversity at an unprecedented continental scale. Moving beyond single-city case studies enables the quantification and comparison of urban ecological functions across diverse human and environmental contexts, revealing emergent patterns that smaller scale analyses might miss. By mapping stopover hotspots and integrating demographic variables, the researchers paint a multi-layered picture of urban ecological networks that could guide targeted conservation efforts.

From a technical standpoint, radar remote sensing excels in capturing the vertical and horizontal movements of birds, providing high-resolution spatial and temporal data essential for identifying key stopover habitats. This capability bypasses many limitations of manual monitoring or static camera traps, especially in densely populated or inaccessible urban environments. Processing and interpreting such voluminous data necessitates sophisticated computational models that account for variability in bird flight altitude, weather conditions, and radar signal attenuation. The study’s success in this regard highlights the potential for radar-based monitoring to become a cornerstone technology in future urban biodiversity research.

The study also touches on the broader concept of cities as integrative nodes within hemispheric-scale ecological processes. Migratory birds traverse vast landscapes, relying on a network of suitable stopover sites to refuel and rest. Urban areas are increasingly embedded within these networks and can either augment or disrupt migratory connectivity. Recognizing their role shifts conservation paradigms and urges urban planners and policymakers to consider migratory birds in urban development strategies. This could lead to innovations in urban design that harmonize human infrastructure with the requirements of migratory species, such as preserving or enhancing green corridors, minimizing night-time light pollution, and incorporating bird-friendly landscaping.

Moreover, the findings challenge the prevailing dichotomy that views urbanization and conservation as inherently opposed forces. Instead, they advocate for a balanced perspective that acknowledges cities’ potential to contribute positively to biodiversity if managed judiciously. This has ramifications for how natural scientists, urban ecologists, and city planners collaborate to design multi-functional urban spaces. It also calls attention to the urgency of integrating equity and inclusivity in urban ecological initiatives, ensuring that the benefits of green spaces and biodiversity are accessible to diverse social groups.

As urban areas continue to expand globally, especially in biodiversity-rich regions, this research underscores the importance of scaling up ecological assessments to capture complex intercity variability. Large-scale, cross-regional datasets coupled with emerging technologies like radar remote sensing can empower scientists to unravel how urbanization patterns modulate ecological processes that transcend local or regional boundaries. Such insights are invaluable for crafting adaptive conservation strategies tuned to the evolving dynamics of human-nature interactions in the Anthropocene.

The study’s interdisciplinary approach, blending ecology, remote sensing technology, and socio-demographic analysis, sets a new benchmark for urban ecological research. It demonstrates that urban environments are neither mere backdrops nor outright obstacles to wildlife but dynamic systems where species and people coexist in intricate, sometimes unexpected ways. This paradigm shift encourages a rethinking of urban ecology to embrace multiple scales of analysis and diverse data sources, fostering more resilient and inclusive urban futures.

Finally, the capacity to monitor migratory behavior at continental scales through radar offers promising avenues for future research on climate change impacts, urban expansion trends, and conservation policy effectiveness. It enables real-time tracking of shifts in migration corridors, responses to changing urban landscapes, and identification of emerging ecological hotspots. Such proactive monitoring could facilitate timely interventions, helping mitigate biodiversity loss and preserve essential ecosystem functions amid rapid anthropogenic change.

In sum, this pioneering research delivers compelling evidence that urban areas are integral to the life cycles of migratory birds at a hemispheric scale. It bridges gaps between ecological theory, technological innovation, and socio-economic realities, mapping a pathway toward smarter urban design and biodiversity stewardship. As cities worldwide grapple with sustainability challenges, integrating biodiversity considerations informed by large-scale empirical data will be paramount to nurturing healthy ecosystems and enriching urban life for all inhabitants.

Subject of Research: Migratory bird stopover patterns in relation to urbanization and social landscapes across the United States.

Article Title: Migratory bird stopover patterns linked to urbanization and social landscapes.

Article References:

Jimenez, M.F., McCaslin, H.M., Belotti, M.C.T.D. et al. Migratory bird stopover patterns linked to urbanization and social landscapes. Nat Cities 3, 167–175 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-025-00388-7

Image Credits: AI Generated

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-025-00388-7

Keywords: Urban ecology, migratory birds, stopover hotspots, radar remote sensing, urbanization, social demographics, biodiversity, flyways, conservation, urban planning

Tags: advanced radar technology in ecologybird migration behavior in anthropogenic environmentscontinental scale bird migration mappingecological role of urban parks for birdshabitat fragmentation and bird stopoversimpact of urbanization on migratory birdsinteraction of urban landscapes and natural ecosystemslarge-scale urban biodiversity studiesmigratory bird stopover patterns in citiesradar remote sensing for bird migrationsocial factors influencing bird migrationurban ecology and migratory birds