In a groundbreaking study, scientists at Johns Hopkins University have made significant strides in our understanding of retinal development and its implications for vision health. This research reveals critical interactions between vitamin A derivatives, specifically retinoic acid, and thyroid hormones during early fetal development in humans, providing new insights into how our eyes develop the capacity for sharp vision.

Traditionally, it has been assumed that the eye develops light-sensing cells, known as photoreceptors, primarily through a passive migration of different cell types during early development. However, the Johns Hopkins team has overturned this conventional theory, offering a novel perspective that emphasizes active transformation and specification of retinal cell types in the foveola, the central region of the retina responsible for acute visual acuity.

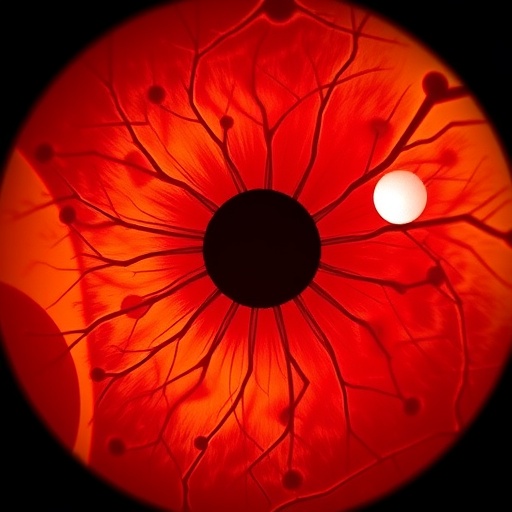

The foveola is a unique feature of the human retina. Unlike most common models used in laboratory studies—such as mice and fish—humans possess a distinct pattern of cones, the photoreceptors responsible for color vision. This arrangement allows humans to perceive a wide spectrum of colors, an ability that is not found in many other species. The recent research demonstrates that the distribution of these cones results from tightly coordinated processes following cell fate specification during the crucial weeks of fetal development.

In the early stages, between weeks ten and twelve, a small population of blue cones appears in the foveola. However, as development progresses, by week fourteen, these blue cones undergo a remarkable transformation into red and green cones. The new evidence indicates that this transition is driven by two primary processes. The breakdown of retinoic acid leads to a decrease in blue cone formation, while the presence of thyroid hormones facilitates the conversion of existing blue cones into their red and green counterparts.

Robert J. Johnston Jr., the associate professor of biology at Johns Hopkins University who led the study, emphasized the significance of these findings in understanding the functioning of the foveola. He remarked that this area experiences the initial failures in people suffering from macular degeneration, a condition that leads to blurred central vision over time. By elucidating the mechanisms governing cell type transition during retinal development, the team aims to develop therapeutic approaches focused on restoring vision.

This innovative research primarily utilized lab-grown retinal organoids—small clusters of retinal cells induced from human fetal stem cells. Monitoring these organoids over several months provided the team with integrative insights into the biological and cellular mechanisms governing the development of foveolar cone types. The movement away from traditional research methods towards this organoid model signifies a major advancement in the study of ocular biology.

The implications of these discoveries extend beyond theoretical understanding; they may inform practical approaches toward treating various vision disorders such as glaucoma or diabetic retinopathy. Vision loss due to these conditions remains a significant public health concern, and the path forward may be illuminated by this foundational work in understanding retinal cell development.

The shift in understanding from passive to active cell fate conversion resonates deeply within the broader scientific community. For decades, researchers operated under the assumption that the movement of blue cones away from the foveola occurred passively. Johnston’s findings suggest an intricate interplay of biochemical signals and mechanistic processes that dictate how these cones are specified and transformed into more visually efficient cell types. The research challenges prevailing models and highlights the necessity for further exploration into the underlying mechanisms of retinal development.

In the ongoing quest to engineer retinal replacements using organoids, the lessons learned about cell conversion may play a crucial role. By creating organoids that closely mimic the natural functioning of the human retina, there lies the potential for the advent of cell-based restorative therapies. The advancements in organoid technology are paving the way for developing customized populations of photoreceptors that could eventually be used in therapeutic contexts.

The research has received accolades not only for its innovative approach but for its potential real-world applications. Johnston’s team is committed to refining their organoid models to ensure they replicate the human retina more accurately. This precision is essential for future studies that could lead to effective and safe therapies for conditions like macular degeneration, which currently has no cure.

Katarzyna Hussey, a former doctoral student involved in the research, articulated the vision of utilizing organoid technology to create precise, patient-specific photoreceptors for cell replacement therapy. She explains the importance of ensuring that these cells can successfully integrate into the existing retinal network to restore vision effectively. The hope is that, with continued research and development, a viable solution for vision restoration could be on the horizon, offering renewed sight to those affected by retinal degeneration.

As these studies progress, safety and efficacy remain paramount concerns that will guide future clinical applications. The exploration of cellular mechanisms through organoid models signifies a bright future for research in regenerative medicine and ophthalmology. The understanding that blue cones convert, rather than migrate, radically shifts the conversation and enhances our understanding of the developmental biology behind vision.

In summary, the intricate processes governing retinal development revealed by the Johns Hopkins study challenge our long-held beliefs about photoreceptor formation and distribution. With innovative research emerging from the use of organoids and a novel understanding of cellular conversion, the potential for groundbreaking therapies that restore lost vision becomes not just a hopeful possibility but a tangible goal for the future of vision science.

Subject of Research: Interplay of vitamin A derivatives and thyroid hormones in retinal development.

Article Title: A cell fate specification and transition mechanism for human foveolar cone subtype patterning.

News Publication Date: 13-Feb-2026.

Web References: http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2510799123.

References: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Image Credits: Will Kirk/Johns Hopkins University.

Keywords

Retinal development, organoids, cell development, photoreceptors, vision restoration.

Tags: active transformation of retinal cellsadvances in retinal biologycolor vision in humansdifferences between human and animal retinasfoveola and visual acuityimplications for vision healthJohns Hopkins University retinal studylab-grown retinas researchphotoreceptors development in humansretinal developmentthyroid hormones and visionvitamin A derivatives in eye health