In a groundbreaking study published in the open-access journal Open Quaternary, a team of researchers from the University of Copenhagen and the University of the Basque Country has unveiled new insights into the geographic ranges of the wild plant ancestors pivotal to the dawn of agriculture in West Asia. These findings reconstruct the habitats of 65 wild crop progenitors, including the ancestors of staples such as wheat, barley, rye, and lentils, which collectively ignited the transformative agricultural revolution over 10,000 years ago. This research not only reshapes our understanding of ancient ecosystems but also highlights the complexity of human-plant interactions during the Neolithic transition.

The earliest farming societies emerged around 12,000 years ago in the Middle East, a period marked by profound cultural and environmental change. Archaeological excavations have long provided tangible evidence in the form of artifacts, seeds, and animal remains from these early communities, furnishing clues about their subsistence strategies. However, the natural vegetation backdrop from which these ancestral crops were sourced remained elusive. The new study addresses this critical gap by pinpointing the ancient geographic distributions of these wild plant species, thereby illuminating where early farmers likely gathered the raw materials for domestication.

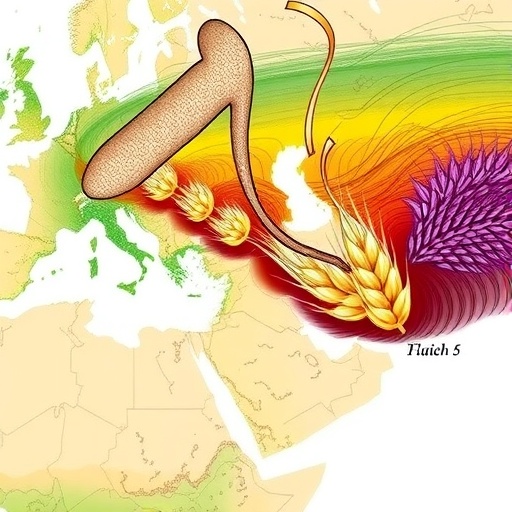

Significantly, the researchers discovered that the progenitors of vital cereals such as wheat, rye, and barley did not occupy the regions long assumed by scholars. Contrary to previous theories suggesting widespread distribution across diverse habitats, these ancestor species appear to have been relatively restricted in range during the terminal Pleistocene. These revelations suggest that early humans selected and adapted plants from a narrower geographic and ecological context than envisioned, prompting a reassessment of the environmental settings of early domestication events.

One particularly unexpected outcome of the study is the identification of the Mediterranean coast of the Levant as a potential refugium—a sanctuary where numerous wild crop ancestors persisted through the harsh climatic conditions of the late Ice Age. This coastal zone, characterized by cold and arid conditions during the terminal Pleistocene, may have served as a critical reservoir for plant diversity that eventually underpinned the Neolithic agricultural toolkit. The idea of the Levantine coast acting as an ecological refuge reshapes the narrative of crop evolution and dispersal.

The adaptive traits of these wild plants challenge existing paradigms. Many species appear highly resilient to cold-dry environments, implying that their evolutionary trajectories were molded under conditions less benign than those of the Holocene agricultural phase. This paints a picture in which early agriculturalists encountered and managed plants already well-suited to climatic extremes, rather than domestication exclusively occurring in newly favorable environments. Such adaptation would have had profound implications for human survival strategies in fluctuating climates.

Methodologically, the study stands at the forefront of paleoecological research by integrating advanced computational techniques. The team employed sophisticated climate simulations—utilizing models analogous to those used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) for future climate projections—but applied retrospectively to reconstruct past climate scenarios. These simulations, combined with machine learning algorithms trained on the ecological preferences of modern wild plant species, enabled the generation of detailed palaeogeographic maps predicting the distribution of ancestral crops thousands of years ago.

This innovative approach eschews some limitations intrinsic to traditional archaeobotanical methods, which often depend on the preservation and discovery of plant remains that can be biased by human activity, sedimentation processes, or excavation practices. Computational modeling offers an independent lens, generating hypotheses about ancient plant distributions free from archaeological sampling constraints. As a result, the study presents a robust complementary framework for interpreting the environmental contexts of early agriculture.

The modeling not only corroborates some previous archaeological findings but also refines them, offering unprecedented spatial resolution in mapping ancient ecosystems. This assists in constructing clearer scenarios regarding how changing climates influenced plant availability and, subsequently, human subsistence choices in West Asia’s shifting landscapes. Furthermore, it facilitates understanding of how domesticated plants might have expanded their ranges following initial cultivation.

These insights have important implications beyond historical curiosity, informing contemporary agricultural science and conservation biology. Understanding how crop progenitors responded to past climatic stressors may yield clues for breeding resilient crops adapted to modern climate challenges. The evolutionary and ecological history encapsulated in these wild species offers a genetic legacy potentially critical for food security in an era of rapid environmental change.

The research is part of the ERC-funded ‘PalaeOrigins’ project, which aims to trace the Epipalaeolithic origins of plant management in Southwest Asia. By bridging archaeology, ecology, and computational sciences, the project exemplifies the interdisciplinary strategies required to tackle complex historical questions. The collaboration between archaeologists and ecologists underscores the importance of combining diverse expertise and methodologies to unravel humanity’s deep past.

Dr. Joe Roe, the study’s lead author and archaeologist at the University of Copenhagen, emphasizes the novelty of these findings, noting that they provide a “whole new window onto the ecological backdrop of the world’s first farmers.” His co-author, archaeobotanist Dr. Amaia Arranz-Otaegui, highlights the cold-dry adaptations of many studied species as a surprising and significant discovery, challenging assumptions about early agricultural environments. Their combined expertise enabled a nuanced interpretation bridging past climates, plant ecology, and human cultural evolution.

Ultimately, this study propels the field forward by demonstrating how computational modeling and large-scale ecological datasets can reconstruct the ancient environment with remarkable clarity. By revealing the true biogeography of early crop progenitors, it enriches our understanding of the agricultural revolution—one of humanity’s most pivotal developments. As such, it not only rewrites chapters of our distant past but also informs how we might steward plant biodiversity amid emerging global challenges.

Subject of Research: Not applicable

Article Title: Biogeography of Crop Progenitors and Wild Plant Resources in the Terminal Pleistocene and Early Holocene of West Asia, 14.7–8.3 ka

News Publication Date: 3-Feb-2026

Web References: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/oq.163

Image Credits: Photo: Joe Roe, University of Copenhagen

Keywords: Neolithic agriculture, crop progenitors, West Asia, terminal Pleistocene, Holocene, paleoclimate modeling, archaeobotany, plant biogeography, computational simulation, climate refugium, Epipalaeolithic, machine learning

Tags: ancient ecosystems in West Asiaancient geographic ranges of wild wheat ancestorsarchaeological evidence of early farming societiesdomestication of wild plantsenvironmental changes during early agriculturehuman-plant interactions in early farmingNeolithic Agricultural Revolutionsubsistence strategies of Neolithic culturesUniversity of Copenhagen research on ancient cropswild barley habitatswild crop progenitors and their significancewild rye progenitors