For centuries, the rapid spread of the Black Death across Asia, particularly along the trade routes of the Silk Road, has been a historical narrative accepted almost uncritically. Traditional accounts have long depicted the plague as a pathogen that swiftly traversed vast distances, propelled by the movements of merchants and caravans. However, recent scholarly inquiry challenges this long-standing view, revealing the mythic roots of these tales and urging a reconsideration of how the Black Death unfolded geographically and temporally during the mid-14th century.

Central to this revised interpretation is the recognition that the primary source for the quick-spread narrative originates from a single literary work composed in the 14th century. Written by the Arab poet and historian Ibn al-Wardi during the devastating years of 1348 and 1349 in Aleppo, this source is not a straightforward historical chronicle. Instead, it belongs to the maqāma genre—a form of Arabic rhymed prose that often features clever, itinerant characters, blending fiction with social commentary. Ibn al-Wardi’s work personifies the plague as a trickster figure, a literary conceit that dramatizes the disease’s movement as a series of bewitched deceptions rather than a literal epidemiological account.

The implications of this insight are profound when considering the “Quick Transit Theory,” which posits that the bacterium responsible for the Black Death originated in Central Asia, specifically Kyrgyzstan, during the late 1330s and rapidly traveled across more than 3,000 miles overland. This theory suggests the pathogen swiftly made its way from the steppes to the Black and Mediterranean seas, precipitating the catastrophic pandemics that ravaged Western Eurasia and North Africa by the late 1340s. Genetic studies supporting this rapid spread have heavily relied on Ibn al-Wardi’s narrative, accepting it as historically factual despite its literary nature.

New research conducted by historians specializing in Arab and Islamic studies calls this literal reading into question, highlighting that Ibn al-Wardi’s maqāma was intended as a dramatic and allegorical story rather than a precise epidemiological log. Subsequent historians—both Arab scholars in the 15th century and later European chroniclers—misinterpreted the maqāma, inadvertently cementing the myth of a swift and linear plague progression. This suggests that many accepted timelines and routes of the plague’s spread across Asia could be built on a foundation of literary allegory rather than corroborated evidence.

This revelation is rooted in understanding the maqāma as a narrative form. Invented in the late 10th century and flourishing during the later medieval period, maqāmāt were often designed for oral performance, utilizing rhyme, humor, and rhetorical flair to convey moral or social themes. Fourteenth-century Mamluk literati especially prized the form, crafting stories that engaged listeners emotionally while not necessarily committing to historical accuracy. Thus, the plague maqāmas, including Ibn al-Wardi’s Risāla, served as a cultural tool for making sense of societal trauma, not as epidemiological bulletins.

Recognizing the literary nature of these narratives frees historians to investigate earlier and parallel plague outbreaks outside the dominant transmission narrative. For example, significant epidemics in locations such as Damascus in 1258 and Kaifeng in 1232-3 are often overshadowed by the focus on the Black Death’s transit in the 1340s. Reevaluating these events within their local and historical contexts allows for a more nuanced comprehension of how societies experienced and remembered plague’s devastation, highlighting the complexity of outbreaks beyond simplistic east-to-west waves.

Moreover, this re-examination opens new avenues for interpreting medieval communities’ responses to pandemics. The creation and sharing of plague maqāmas can be seen as a form of collective psychological resilience, channeling fear and uncertainty into storytelling and art. Much like the modern-day COVID-19 pandemic inspired a surge in artistic expression and innovation, the Black Death era also witnessed cultural adaptations serving as coping mechanisms in the face of overwhelming mortality.

Crucially, while these texts do not provide reliable data on the disease’s epidemiology, they are invaluable historical documents. They reveal how people understood and processed the plague’s impact on their lives, social fabric, and belief systems. The personification of the disease as a trickster encapsulates the unpredictable and terrifying nature of the contagion, resonating with modern sensibilities around pandemic trauma and the human need to find meaning amid chaos.

This shift away from a literal interpretation of the Black Death’s movement invites interdisciplinary collaboration. Historians, geneticists, literary scholars, and epidemiologists can jointly reconsider plague transmission models, integrating molecular data with a critical appraisal of primary sources’ narrative forms. Such a holistic approach promises a richer, more accurate reconstruction of medieval pandemics, their origins, and their profound effects on world history.

Ultimately, the study serves as a cautionary tale against accepting historical texts at face value, especially when literary conventions and modes of expression differ significantly from modern historiographical standards. Ibn al-Wardi’s maqāma, while central to shaping century-old myths about the plague, underscores the powerful role of storytelling in shaping collective memory. It challenges scholars to untangle myth from reality to better understand one of humanity’s most devastating pandemics.

By revisiting the sources through this lens, contemporary researchers can also better appreciate the socio-cultural dimensions of plague narratives, revealing their enduring influence on historical consciousness. Such insights shed light on the interplay between narrative, memory, and history, enriching our understanding of how communities across time deal with calamity and loss.

As research progresses, these findings encourage a recalibration of educational materials and public histories surrounding the Black Death. Correcting the record not only advances academic knowledge but also deepens public comprehension of pandemics’ complexities—an especially timely endeavor in the post-COVID-19 world that demands critical engagement with how historic diseases are represented and remembered.

Subject of Research: People

Article Title: Mamluk Maqāmas on the Black Death

News Publication Date: Not specified

Web References: https://journals.uio.no/JAIS/article/view/12790

References: DOI: 10.5617/jais.12790

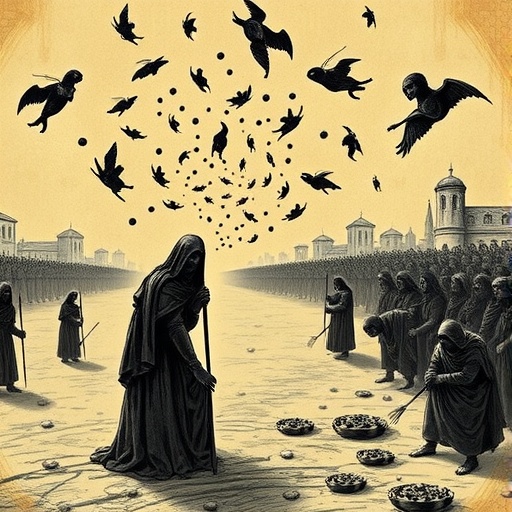

Image Credits: A page from Ibn Abi Hajala’s (d. 1375) Dafʿ al-niqma bi-l-ṣalāh ʿalā nabī al-raḥma (‘Repelling the Trial by Sending Blessings Upon the Prophet of Mercy’). This plague treatise contains four maqamas, three of which were composed in Syria during the 1348/9 Black Death outbreak. (Image credit: MS Laleli 1361, Süleymaniye Library, Istanbul, personal photo).

Keywords: Medical histories, Evolutionary biology, Disease control, Cell pathology

Tags: 14th century historical accountsBlack Death mythsepidemiology and storytellinghistorical revisionism of the Black DeathIbn al-Wardi and the Black Deathliterary influence on historymaqāma genre significanceplague as a literary conceitSilk Road plague narrativesocial commentary in medieval literaturetrade routes and disease spreadunderstanding historical pandemics through literature