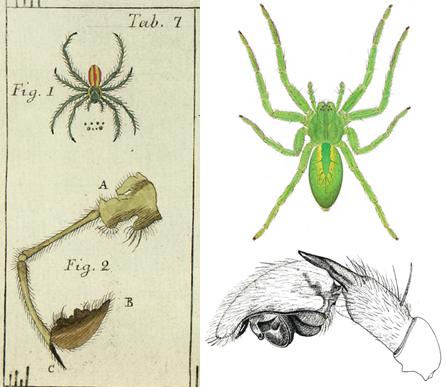

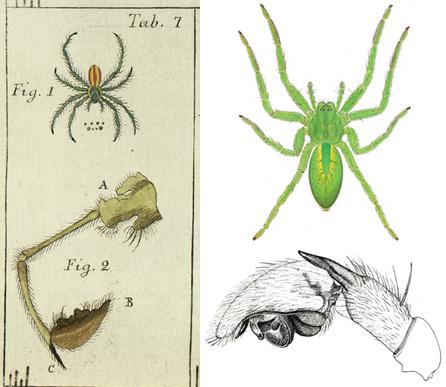

Credit: C. Clerck (1757) (left) and M. Roberts (1985) (right)

It goes without saying that scientific research has to build on previous breakthroughs and publications. However, it feels quite counter-intuitive for data and their re-use to be legally restricted. Yet, that is what happens when copyright restrictions are placed on many scientific papers.

The discipline of taxonomy is highly reliant on previously published photographs, drawings and other images as biodiversity data. Inspired by the uncertainty among taxonomists, a team, representing both taxonomists and experts in rights and copyright law, has traced the role and relevance of copyright when it comes to images with scientific value. Their discussion and conclusions are published in the latest paper added in the EU BON Collection in the open science journal Research Ideas and Outcomes (RIO).

Taxonomic papers, by definition, cite a large number of previous publications, for instance, when comparing a new species to closely related ones that have already been described. Often it is necessary to use images to demonstrate characteristic traits and morphological differences or similarities. In this role, the images are best seen as biodiversity data rather than artwork. According to the authors, this puts them outside the scope, purposes and principles of Copyright. Moreover, such images are most useful when they are presented in a standardized fashion, and lack the artistic creativity that would otherwise make them 'copyrightable works'.

"It follows that most images found in taxonomic literature can be re-used for research or many other purposes without seeking permission, regardless of any copyright declaration," says Prof. David J. Patterson, affiliated with both Plazi and the University of Sydney.

Nonetheless, the authors point out that, "in observance of ethical and scholarly standards, re-users are expected to cite the author and original source of any image that they use." Such practice is "demanded by the conventions of scholarship, not by legal obligation," they add.

However, the authors underline that there are actual copyrightable visuals, which might also make their way to a scientific paper. These include wildlife photographs, drawings and artwork produced in a distinctive individual form and intended for other than comparative purposes, as well as collections of images, qualifiable as databases in the sense of the European Protection of Databases directive.

In their paper, the scientists also provide an updated version of the Blue List, originally compiled in 2014 and comprising the copyright exemptions applicable to taxonomic works. In their Extended Blue List, the authors expand the list to include five extra items relating specifically to images.

"Egloff, Agosti, et al. make the compelling argument that taxonomic images, as highly standardized 'references for identification of known biodiversity,' by necessity, lack sufficient creativity to qualify for copyright. Their contention that 'parameters of lighting, optical and specimen orientation' in biological imaging must be consistent for comparative purposes underscores the relevance of the merger doctrine for photographic works created specifically as scientific data," comments on the publication Ms. Gail Clement, Head of Research Services at the Caltech Library.

"In these cases, the idea and expression are the same and the creator exercises no discretion in complying with an established convention. This paper is an important contribution to the literature on property interests in scientific research data – an essential framing question for legal interoperability of research data," she adds.

###

Original source:

Egloff W, Agosti D, Kishor P, Patterson D, Miller J (2017) Copyright and the Use of Images as Biodiversity Data. Research Ideas and Outcomes 3: e12502. https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.3.e12502

Additional information:

The present study is a research outcome of the European Union's FP7-funded project EU BON, grant agreement No 308454.

Media Contact

Donat Agosti

[email protected]

@Pensoft

http://www.pensoft.net

############

Story Source: Materials provided by Scienmag