A groundbreaking study led by Professor Amos Frumkin from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem offers compelling evidence that radically reshapes our understanding of the Neolithic Revolution in the southern Levant. Contrary to the long-held notion that the transition from hunter-gatherer societies to agriculture was driven predominantly by cultural innovation or anthropogenic factors, this research identifies catastrophic wildfires and climate-driven soil degradation as the principal natural triggers behind this pivotal transformation. Published in the Journal of Soils and Sediments, the study employs a multidisciplinary analytical framework, integrating paleoenvironmental records such as micro-charcoal deposits, isotopic compositions from cave stalagmites, and sediment stratigraphy, to reveal an abrupt environmental tipping point roughly 8,200 years ago.

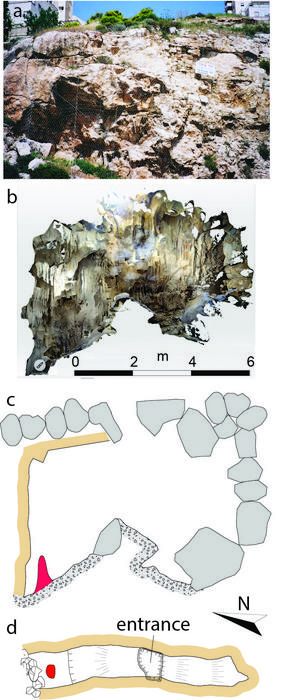

The Neolithic Revolution marked one of humanity’s most profound shifts in subsistence and social organization, yet its precise catalysts have remained enigmatic. Prof. Frumkin’s team analyzed sediment cores from multiple catchments across the southern Levant, focusing particularly on charcoal fragments embedded within lacustrine deposits. These fragments serve as a proxy for historical fire regimes, allowing for detailed reconstruction of wildfire intensity and frequency. Alongside, speleothem samples from the Har Nof Cave near Jerusalem were scrutinized using carbon and strontium isotope analyses, providing insights into past hydrological changes and soil chemistry variations linked to vegetation loss and soil erosion.

Their findings indicate that an extraordinary surge in natural wildfire activity occurred nearly simultaneously across the region, triggered by increased dry lightning incidences during the early Holocene. This surge was likely intensified by orbital-driven shifts in solar radiation, causing climatic instability characterized by dry thunderstorms. Such environmental volatility caused widespread deforestation and vegetation collapse, severely compromising the integrity of hillslope soils. Consequently, the upper hill soils underwent accelerated erosion, which led to the accumulation of nutrient-rich sediments in valley basins. These newly formed fertile deposits created optimal conditions for early agricultural communities to emerge and thrive.

Importantly, the data suggest that this ecological collapse was not a gradual transition but rather a rapid and severe environmental disturbance that forced prehistoric humans to adapt quickly. The disruption of traditional foraging landscapes necessitated new survival strategies, culminating in the domestication of plants and the establishment of permanent settlements in the most agriculturally favorable areas. This scenario challenges the conventional anthropocentric paradigm and reframes the Neolithic Revolution as a primarily climate-forced adaptive response rather than a mere cultural innovation.

The isotopic evidence from the cave speleothems further reinforces this hypothesis by revealing abrupt fluctuations in water availability concurrent with wildfire events. These fluctuations would have had profound effects on regional hydrology, influencing groundwater recharge rates and sediment deposition patterns within valley basins. The interplay between fire-induced vegetation loss and altered water cycles accelerated soil degradation processes on hillslopes, a phenomenon meticulously documented through stratigraphic sequences and mineralogical soil assessments carried out in the study.

Moreover, the research underscores how Neolithic settlements predominantly clustered along the Jordan Valley and other proximal basins where these reworked soils accumulated. The spatial correlation between archaeological sites and fertile sediments is striking, reinforcing the premise that environmental factors dictated early human settlement patterns. Such fertile soils provided the essential nutrient base and moisture retention necessary to support the cultivation of early crops, setting the stage for sustained agrarian economies.

This study also contributes to broader discussions about the role of natural disasters in shaping human history. While wildfires have traditionally been considered destructive forces, here they emerge as inadvertent ecological engineers, transforming landscapes in ways that both challenged and enabled human populations. The fires not only cleared vegetation but also reshaped the geomorphology, creating novel soil environments that became “hotspots” for Neolithic agricultural innovation.

From a methodological perspective, the integration of charcoal analysis with isotopic and sedimentological data exemplifies the power of a multidisciplinary approach in paleoenvironmental reconstruction. The research demonstrates how tightly coupled interactions between climate, fire regimes, and soil dynamics can be dissected to reveal chronological events with great precision. This approach sets a benchmark for future studies examining prehistoric human-environment interactions and the environmental contingencies influencing cultural evolution.

Professor Frumkin’s insights compel us to rethink human resilience and adaptability in the face of abrupt climate perturbations. They remind us that environmental changes—both gradual and sudden—have consistently played a decisive role in shaping human civilizations. Understanding these dynamics is particularly salient today as modern societies confront their own “tipping points” amidst climate-driven ecological crises.

Furthermore, the implications of this research extend beyond archaeology and environmental science into contemporary land management and conservation policies. By elucidating the mechanisms through which fire and soil processes interact over long timescales, the study highlights the delicate balance that sustains fertile landscapes. It also serves as a cautionary tale about the consequences of vegetation loss and soil degradation, issues that remain critically relevant in current times of intensified land use.

In conclusion, this compelling synthesis of evidence revises long-standing narratives about the Neolithic Revolution, situating it within the framework of natural environmental forcings rather than exclusively cultural developments. The identification of catastrophic wildfires and soil erosion as catalysts not only enriches our understanding of early agricultural origins but also underscores the intricate interdependencies between human societies and their changing environments. As climate dynamics continue to evolve, lessons from this ancient transition offer valuable perspectives on the adaptability and vulnerability of humanity.

Subject of Research: Not applicable

Article Title: Catastrophic fires and soil degradation: possible association with the Neolithic revolution in the southern Levant

News Publication Date: 9-Apr-2025

Web References: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11368-025-04021-x

Image Credits: Amos Frumkin and Boaz Langford

Keywords: Archaeology, Soils, Wildfires, Soil fertility, Soil erosion, Sediment, Fire

Tags: ancient sediment stratigraphyclimate-driven wildfiresenvironmental tipping pointshistorical fire regime reconstructioninterdisciplinary climate studiesisotopic composition studiesmicro-charcoal deposits researchNeolithic Agricultural Revolutionpaleoenvironmental records analysissoil erosion and agriculturesouthern Levant archaeological findingswildfire intensity and frequency