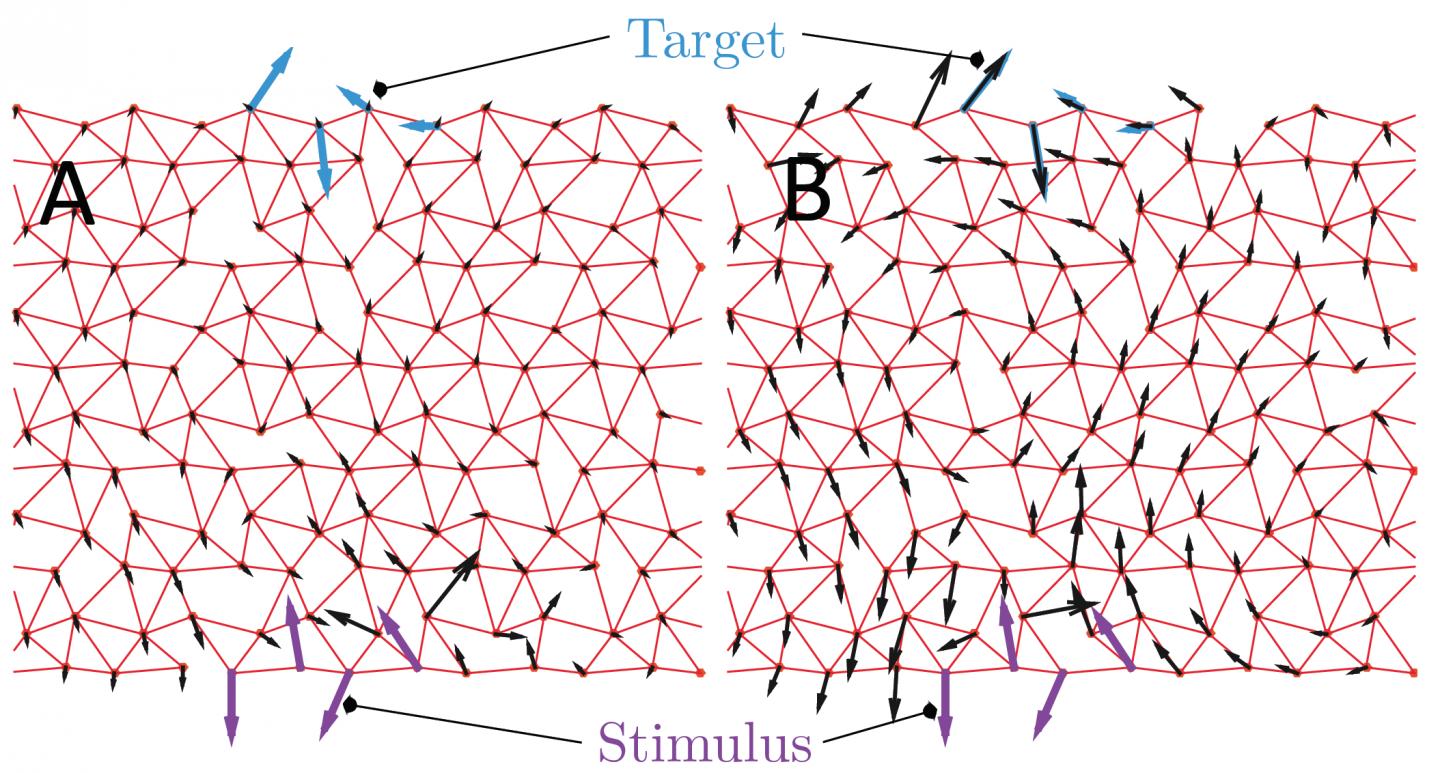

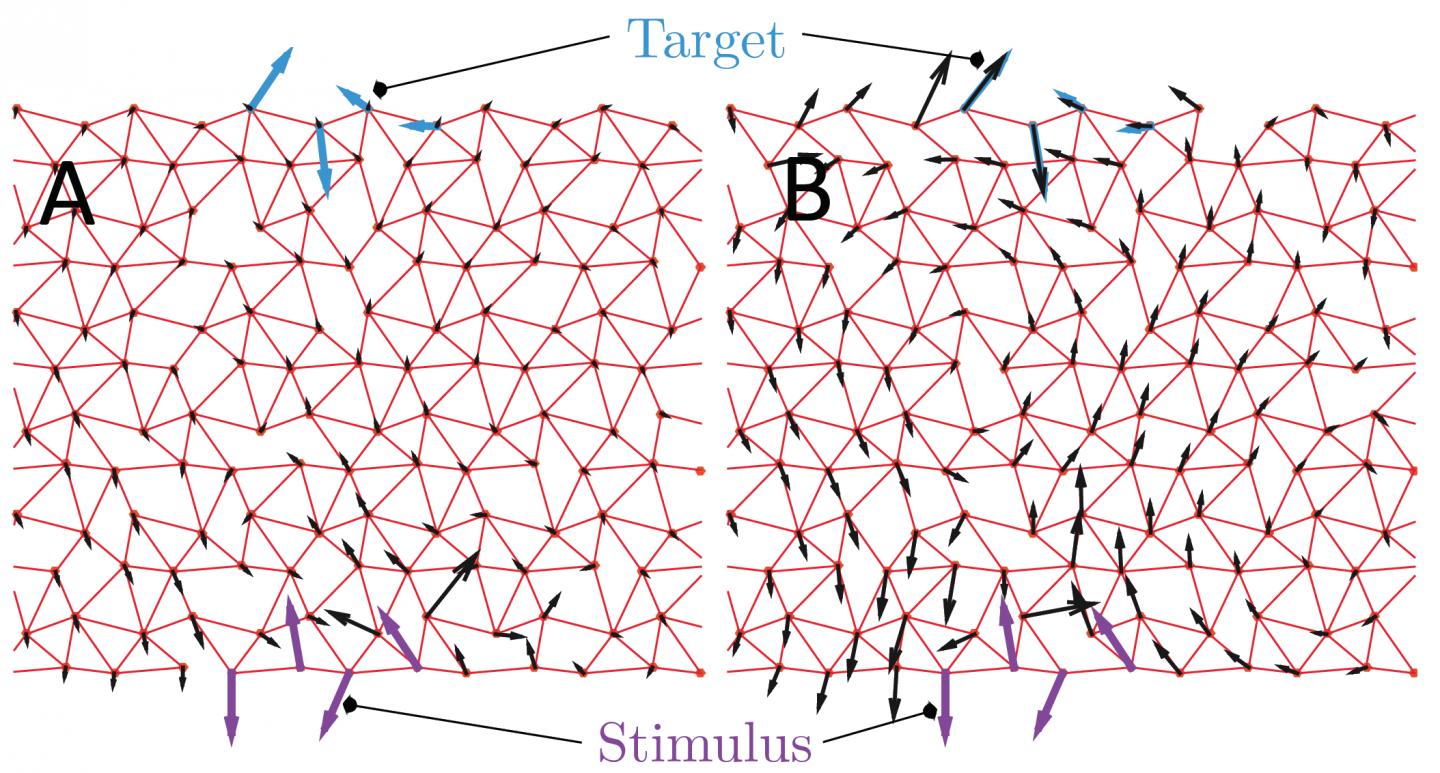

Credit: Matthieu Wyart/EPFL

EPFL scientists have created a new computer model that can help better design of allosteric drugs, which control proteins "at a distance".

Enzymes are large proteins that are involved in virtually every biological process, facilitating a multitude of biochemical reactions in our cells. Because of this, one of the biggest efforts in drug design today aims to control enzymes without interfering with their so-called active sites — the part of the enzyme where the biochemical reaction takes place. This "at a distance" approach is called "allosteric regulation", and predicting allosteric pathways for enzymes and other proteins has gathered considerable interest. Scientists from EPFL, with colleagues in the US and Brazil, have now developed a new mathematical tool that allows more efficient allosteric predictions. The work is published in PNAS.

Allosteric drugs

Allosteric regulation is a fundamental molecular mechanism that modulates numerous cell processes, fine-tuning them and making them more efficient. Most proteins contain parts in their structure away from their active site that can be targeted to influence their behavior "from a distance". When an allosteric modulator molecule — whether natural or synthetic — binds such a site, it changes the 3D structure of the protein, thereby affecting its function.

The main reason allosteric sites are of such interest to drug design is that they can be used to inhibit or improve the activity of a protein, eg. the binding strength of an enzyme or a receptor. For example, diazepam (Valium) acts on an allosteric site of the GABAA receptor in the brain, and increases its binding ability. Its antidote, flumazenil (Lanexat), acts on the same site, but instead inhibits the receptor.

Generally speaking, an allosteric drug would also be used at a comparatively lower dose than a drug acting directly on the protein's active site, thus providing more effective treatments with fewer side effects.

Developing an allosteric model

Despite the importance of allosteric processes, we still do not fully understand how a molecule binding on a distant and seemingly unimportant part of a large protein can change its function so dramatically. The key lies in the overall architecture of the protein, which determines what kinds of 3D changes an allosteric effect will have.

The lab of Matthieu Wyart at EPFL sought to address several questions regarding our current understanding of allosteric architectures. Scientists classify these into two types: hinges, which cause scissor-like 3D changes, and shear, which involve two planes moving side-by-side. Despite being clear mechanically, the two models do not capture all cases of allosteric effects, where certain proteins cannot be classified as having either hinge or shear architectures.

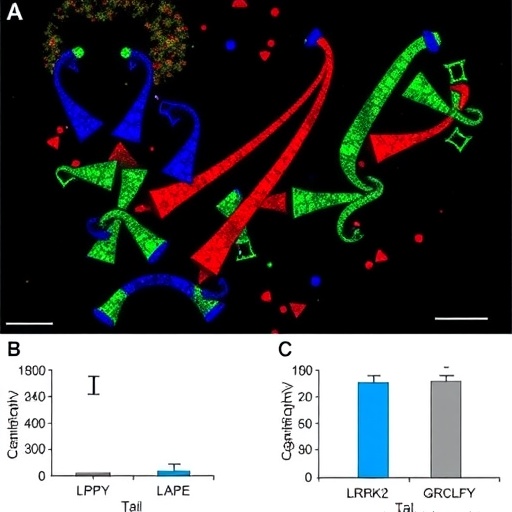

The researchers explored alternative allosteric architectures. Specifically, they looked at the structure of proteins as randomly packed spheres that can evolve to accomplish a given function. When one sphere moves a certain way, this model can help scientists track its structural impact on the whole protein.

Using this approach, the scientists addressed several questions that conventional models do not answer satisfactorily. Which types of 3D "architecture" are susceptible to allosteric effects? How many functional proteins with a similar architecture are they? How can these be modeled and evolved in a computer to offer predictions for drug design?

Using theory and computer power, the team developed a new model that can predict the number of solutions, their 3D architectures and how the two relate to each other. Each solution can even be printed in a 3D printer to create a physical model.

The model proposes a new hypothesis for allosteric architectures, introducing the concept that certain regions in the protein can act as levers. These levers amplify the response induced by binding a ligand and allow for action at a distance. This architecture is an alternative to the hinge and shear designs recognized in the past. The computational approach can also be used to study the relationship between co-evolution, mechanics, and function, while being open to many extensions in the future.

###

This work involves a collaboration of EPFL's Physics of Complex Systems Laboratory with the University of California Santa Barbara and the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil. It was funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), and the Simons Foundation.

Reference

Le Yan, Riccardo Ravasio, Carolina Brito, Matthieu Wyart. Architecture and Co-Evolution of Allosteric Materials. PNAS 20 February 2017.

Media Contact

Nik Papageorgiou

[email protected]

41-216-932-105

@EPFL_en

http://www.epfl.ch/index.en.html

############

Story Source: Materials provided by Scienmag