Perfectly adapted microorganisms live in extreme environments from deep-sea trenches to mountaintops. Learning more about how these extremophiles survive in hostile conditions could inform scientists about life on Earth and potential life on other planets. In ACS’ Journal of Proteome Research, researchers detail a method for more accurate extremophile identification based on protein fragments instead of genetic material. The study identified two new hardy bacteria from high-altitude lakes in Chile — an environment like early Mars.

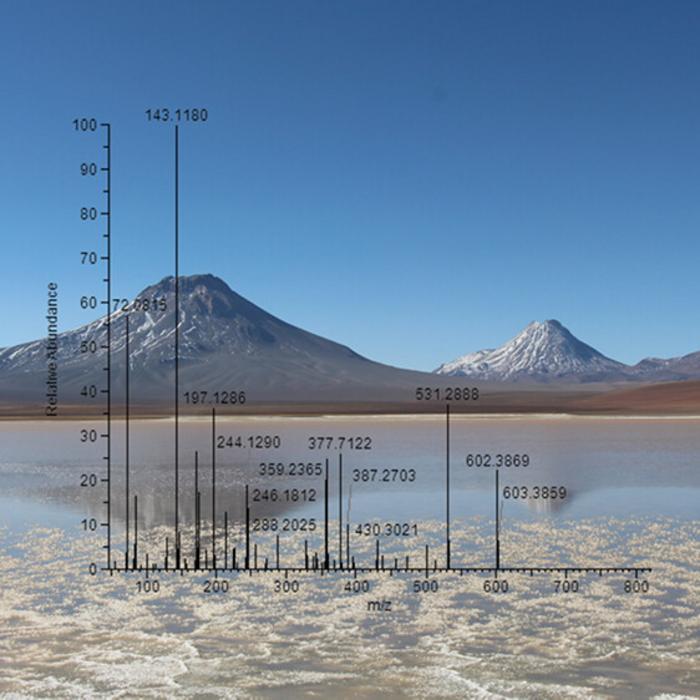

Credit: Adapted from Journal of Proteome Research 2024, DOI: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.3c00538

Perfectly adapted microorganisms live in extreme environments from deep-sea trenches to mountaintops. Learning more about how these extremophiles survive in hostile conditions could inform scientists about life on Earth and potential life on other planets. In ACS’ Journal of Proteome Research, researchers detail a method for more accurate extremophile identification based on protein fragments instead of genetic material. The study identified two new hardy bacteria from high-altitude lakes in Chile — an environment like early Mars.

Even though humans tend to avoid settling in extremely hot, cold or high-altitude areas, some microorganisms have adapted to live in such harsh locations. These extremophile microbes are of interest to astrobiologists who are searching for life on other planets. Researchers currently use individual gene sequencing to identify Earth-bound microbes, based on their DNA. However, current methods can’t distinguish closely related species of extremophiles. So, Ralf Moeller and colleagues investigated whether they could identify an extremophile by using its protein signature rather than a gene sequence.

The researchers started their demonstration with water samples from five high-altitude Andean lakes more than 2.3 miles above sea level in the Chilean Altiplano. (For reference, Denver is about one mile above sea level.) From the samples, the researchers cultivated 66 microbes and then determined which of two methods better identified the microorganisms:

- Traditional gene sequencing compared the nucleotides of the 16s rRNA gene (a typical gene for sequence-based microbe analysis) from each sample to a database for identification.

- The newer “proteotyping” technique analyzed protein fragments known as peptides to produce peptide signatures, which the team used to identify microorganisms from proteome databases.

With these methods, the researchers identified 63 of the 66 microorganisms that were cultivated from the high-altitude lake samples. For the three microorganisms that gene sequencing failed to identify because their genetic information wasn’t in the available database, proteotyping identified two potentially new types of extremophile bacteria. These results suggest proteotyping could be a more complete solution for identifying extremophile microorganisms from small biological samples. The team says protein profiling could someday help us search for and identify extraterrestrial life and better explore the biodiversity on our own planet.

The authors acknowledge funding from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research-Association of German Engineers and the Association of Electrical, Electronic and Information Technologies Innovation + Technology grant; German Aerospace Center; German Research Foundation; an Occitania Region grant; and the Volkswagen Foundation.

###

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS’ mission is to advance the broader chemistry enterprise and its practitioners for the benefit of Earth and all its people. The Society is a global leader in promoting excellence in science education and providing access to chemistry-related information and research through its multiple research solutions, peer-reviewed journals, scientific conferences, eBooks and weekly news periodical Chemical & Engineering News. ACS journals are among the most cited, most trusted and most read within the scientific literature; however, ACS itself does not conduct chemical research. As a leader in scientific information solutions, its CAS division partners with global innovators to accelerate breakthroughs by curating, connecting and analyzing the world’s scientific knowledge. ACS’ main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

To automatically receive news releases from the American Chemical Society, contact [email protected].

Note: ACS does not conduct research, but publishes and publicizes peer-reviewed scientific studies.

Follow us: X, formerly Twitter | Facebook | LinkedIn | Instagram

Journal

Journal of Proteome Research

DOI

10.1021/acs.jproteome.3c00538

Article Title

Exploring Andean High-Altitude Lake Extremophiles through Advanced Proteotyping

Article Publication Date

20-Feb-2024