LA JOLLA, CA—Hitting targets embedded within the cell membrane has long been difficult for drug developers due to the membrane’s challenging biochemical properties. Now, Scripps Research chemists have demonstrated new custom-designed proteins that can efficiently reach these “intramembrane” targets.

Credit: Marco Mravic, Scripps Research

LA JOLLA, CA—Hitting targets embedded within the cell membrane has long been difficult for drug developers due to the membrane’s challenging biochemical properties. Now, Scripps Research chemists have demonstrated new custom-designed proteins that can efficiently reach these “intramembrane” targets.

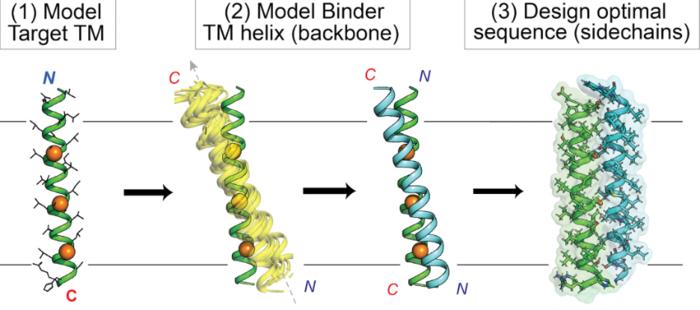

In their study, published March 13, 2024, in Nature Chemical Biology, the researchers used a unique computer-based approach to design novel proteins targeting the membrane-spanning region of the erythropoietin (EPO) receptor, which controls red blood cell production and can go awry in cancers. In addition to these new EPO-targeting molecules, the study yielded a general computational process, or “workflow,” for streamlining the flexible custom design of proteins aimed at intramembrane targets.

The researchers are now using their approach to develop potential new intramembrane-targeting treatments across a wide range of diseases.

“This work opens up many new possibilities for the modulation of targets within the cell membrane, including for therapeutic applications and understanding signaling mechanisms across cell biology,” says study co-corresponding author Marco Mravic, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Integrative Structural and Computational Biology at Scripps Research.

The study’s other co-corresponding authors were Daniel DiMaio, MD, PhD, of the Yale School of Medicine; and William DeGrado, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco School of Pharmacy, where Mravic was previously a PhD student.

“A major goal of synthetic biology is to design proteins with biological activity—here, we report the design and testing of a small protein that specifically perturbs the activity of a much larger protein receptor involved in blood cell growth and differentiation,” says DiMaio, who is a professor of Genetics and of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry, and deputy director of Yale Cancer Center. “We accomplished this by targeting the segment of the receptor that crosses the cell membrane. Because many cell proteins contain structurally conserved membrane-spanning segments, this general approach may be applicable to many other protein targets and provides a new tool to modulate the behavior of cells.”

Hitting intramembrane targets has long been an important goal in biomedicine since many proteins in cells—especially receptor proteins—have functionally important domains inside the membrane. Such proteins have prominent roles in almost every area of health and disease.

Yet intramembrane targets are not ordinary targets. Cell membranes generally are made of two layers of tightly spaced, fat-related “lipid” molecules, which are water-repellent and have other unique and complex properties. This makes the intramembrane space a much harder target for drug designers, compared to the watery zones of cell surfaces or interiors.

“There have been very few successful examples of drugs that target this space inside the membrane,” Mravic says.

Those few successes, which include treatments for low-blood-platelet disorders and cystic fibrosis, have come from blind screenings of large compound libraries or from close mimicry of proteins known to interact with partner proteins within the cell membrane. By contrast, Mravic and colleagues set out to design completely novel proteins—small ones called peptides—to hit intramembrane protein targets in new and diverse ways. To do that, they had to extend the frontier of computational methods, combining “data mining” of known protein-to-protein interactions in membranes with traditional physics-based predictions of protein interactions.

Ultimately, Mravic and his colleagues designed the first proteins that bind the EPO receptor’s membrane-spanning portion in a new way—not seen in nature. The team showed that these proteins very specifically and potently block the receptor’s function, in contrast to prior approaches.

The results may be of most immediate interest to researchers seeking new ways to inhibit the EPO receptor, which is often abnormally activated by tumor cells to maintain their growth and survival. But for Mravic and his colleagues, the study above all represents a proof of principle of a new and more flexible approach to intramembrane targeting.

“We intend to use this approach to target membrane proteins across multiple biological processes and disease areas, including cancers, immune disorders, and pain,” Mravic says.

He also expects the computational workflow he designed for the project to be a general accelerator of membrane-targeting drug design.

“Before, the process basically involved two people in a dark room looking at a computer screen and saying, ‘Yeah, I think this looks better than that,’” Mravic says. “Now, we’ve automated a lot of that molecule design process and decision making in the computer. Being more modular, flexible and streamlined allows the method to be more accessible for a broader range of scientists.”

Mravic and his colleagues have posted their computational tools for public use on Github: https://github.com/mmravic314/CHAMP2023/.

“De Novo Transmembrane Proteins Designed to Bind and Inhibit a Cytokine Receptor” was co-authored by Marco Mravic, Li He, Huong Kratochvil, Hailin Hu, Sarah Nick, Weiya Bai, Anne Edwards, Hyunil Jo, Yibing Wu, Daniel DiMaio and William DeGrado.

Support for the research came from the National Institutes of Health (R35-122603, CA037157, GM68933) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

About Scripps Research

Scripps Research is an independent, nonprofit biomedical institute ranked one of the most influential in the world for its impact on innovation by Nature Index. We are advancing human health through profound discoveries that address pressing medical concerns around the globe. Our drug discovery and development division, Calibr, works hand-in-hand with scientists across disciplines to bring new medicines to patients as quickly and efficiently as possible, while teams at Scripps Research Translational Institute harness genomics, digital medicine and cutting-edge informatics to understand individual health and render more effective healthcare. Scripps Research also trains the next generation of leading scientists at our Skaggs Graduate School, consistently named among the top 10 US programs for chemistry and biological sciences. Learn more at www.scripps.edu.

Journal

Nature Chemical Biology

DOI

10.1038/s41589-024-01562-z