Snail shells are often colourful and strikingly patterned. This is due to pigments that are produced in special cells of the snail and stored in the shell in varying concentrations. Fossil shells, on the other hand, are usually pale and inconspicuous because the pigments are very sensitive and have already decomposed. Residues of ancient colour patterns are therefore very rare. This makes this new discovery by researchers from the University of Göttingen and the Natural History Museum Vienna (NHMW) all the more astonishing: they found pigments in twelve-million-year-old fossilised snail shells. These are the world’s first pigments from the chemical group of polyenes that have been preserved almost unchanged and found in fossils. The study was published in the journal Palaeontology.

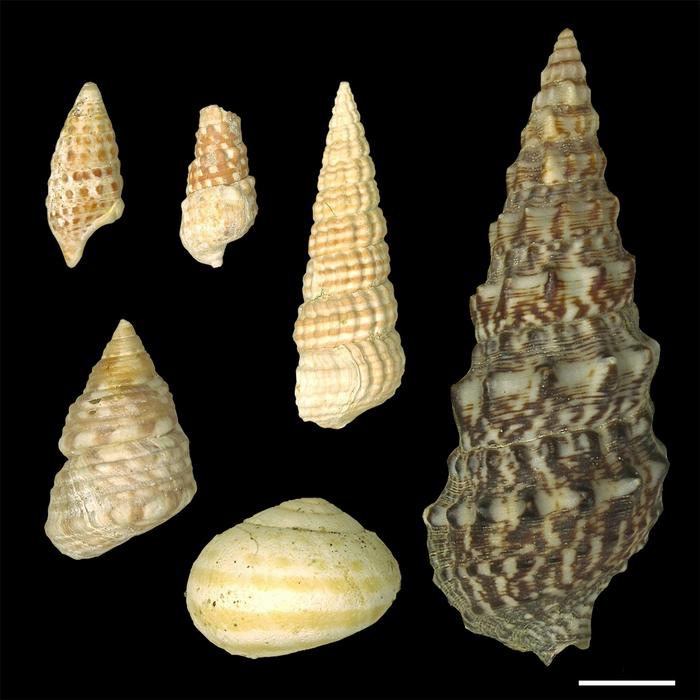

Credit: Klaus Wolkenstein

Snail shells are often colourful and strikingly patterned. This is due to pigments that are produced in special cells of the snail and stored in the shell in varying concentrations. Fossil shells, on the other hand, are usually pale and inconspicuous because the pigments are very sensitive and have already decomposed. Residues of ancient colour patterns are therefore very rare. This makes this new discovery by researchers from the University of Göttingen and the Natural History Museum Vienna (NHMW) all the more astonishing: they found pigments in twelve-million-year-old fossilised snail shells. These are the world’s first pigments from the chemical group of polyenes that have been preserved almost unchanged and found in fossils. The study was published in the journal Palaeontology.

Palaeontologists from the NHMW found snail shells of the superfamily Cerithioidea in Burgenland, Austria. The snails lived there twelve million years ago on the shores of a tropical sea. Professor Mathias Harzhauser at NHMW, who was involved in the discovery, explains: “It was unclear whether the patterns of reddish colour were from the original shell or were formed by later processes in the sediment.” Researchers at Göttingen University’s Geoscience Center solved the mystery. They analysed the pigments using Raman spectroscopy. This involves irradiating samples with laser light. The scattered light reflected from the sample can be used to clearly identify chemical compounds. They detected pigments in the fossilised shells that belong to the polyene group of chemicals. These are organic compounds that include the well-known “carotenoids”, which are responsible for producing the vibrant red, orange and yellow colours seen in birds’ feathers, carrots and egg yolks, for instance.

Dr Klaus Wolkenstein, who led the study and has been researching the chemistry of fossil pigments at Göttingen University for many years, explains: “Normally, after such a long period of time, the best we can hope for is that there are traces of degradation products of these chemicals. If degraded, however, these compounds would be devoid of colour. So, it was really surprising to discover these pigments, preserved almost intact, in fossils that are twelve million years old.”

Original publication: Wolkenstein, K. et al. Detection of intact polyene pigments in Miocene gastropod shells. Palaeontology (2024). DOI: 10.1111/pala.12691

Contact:

Dr Klaus Wolkenstein

University of Göttingen

Geoscience Center, Geobiology

Goldschmidtstraße 3, 37077 Göttingen, Germany

Tel: +49 (0)551 39-7962

Email: [email protected]

www.uni-goettingen.de/en/653377.html

Professor Mathias Harzhauser

Natural History Museum Vienna

Tel: +43 (0)1 52177-250

Email: [email protected]

Journal

Palaeontology

DOI

10.1111/pala.12691

Method of Research

Experimental study

Subject of Research

Not applicable

Article Title

Detection of intact polyene pigments in Miocene gastropod shells. Palaeontology

Article Publication Date

1-Feb-2024