PFAS are highly versatile chemicals. These fluorine-containing organic molecules are the reason why rain drops simply slide off outdoor jackets. They are used in the greaseproof coating of paper food packaging and are key ingredients in fire-extinguisher foams and the protective gear worn by firefighters. PFAS were first introduced in the 1940s and since then, the number of products and areas in which they are used has grown astronomically.

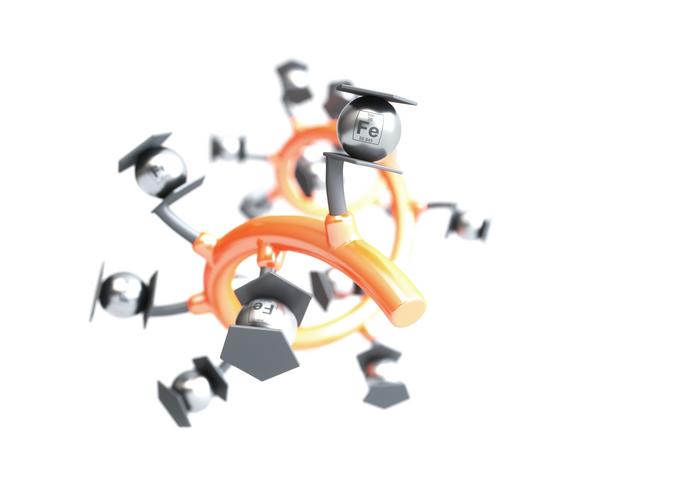

Credit: Markus Gallei

PFAS are highly versatile chemicals. These fluorine-containing organic molecules are the reason why rain drops simply slide off outdoor jackets. They are used in the greaseproof coating of paper food packaging and are key ingredients in fire-extinguisher foams and the protective gear worn by firefighters. PFAS were first introduced in the 1940s and since then, the number of products and areas in which they are used has grown astronomically.

And that’s where the problem lies. Because they are so inert and there are no natural pathways by which they can be broken down, these highly persistent chemicals accumulate in the natural environment – posing a problem for human health and the environment. PFAS have now been detected all over the planet: in water, soil and air, in plants, animals and – at the end of the food chain – in humans, too. Just how much of a health risk these chemicals pose is still not clear. Initial laboratory animal studies have shown that PFAS may impair reproductive health. What is clear is that these synthetic compounds do not belong in the natural environment and certainly not in living organisms. It therefore makes sense to find ways to try and reduce PFAS contamination levels in the environment.

But PFAS remediation is both complex and challenging, and the processes used can themselves have a detrimental impact on the environment and the climate. And before they can be removed, the PFAS have to be detected. Detection is not made any easier by the fact that only small quantities of PFAS are required for a large effect (e.g. the ultra-thin coatings in food packaging). Conventionally, PFAS have been removed from water by filtration using special membranes or lower-cost activated carbon adsorbents. However, recovering the PFAS from these filter systems so that they can be permanently destroyed either requires the use of harsh chemical conditions or incineration.

At least that has been the case up to now. A team of researchers led by Markus Gallei, Professor of Polymer Chemistry at Saarland University, Professor Xiao Su from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and their doctoral students Frank Hartmann (Saarland) and Paola Baldaguez (Illinois) have developed a new electrochemical method that can remove PFAS chemicals from water and then efficiently release them again for destruction. This new PFAS remediation platform allows these fluorinated contaminants to be collected, identified and then destroyed without needing to incinerate the filter.

In the method developed by the research team, the central role is played by metal-containing polymers known as metallocenes. Metallocenes first came on the scene in 1951 with the discovery of the iron-containing molecule ferrocene. Since then, many other metallocenes have been reported. Frank Hartmann, Markus Gallei and their international team have found that electrodes functionalized with ferrocene or – even more effectively – with a cobaltocene synthesized by Frank Hartmann, are able to remove even minute quantities of PFAS molecules from water.

But the real key lies in the fact that if a voltage is applied to the ferrocene or cobaltocene metallopolymers, they can ‘switch’ their electrical state and release the PFAS molecules previously captured. ‘And cobalt is significantly better at doing this than iron,’ observed Frank Hartmann. ‘We’ve found a means by which PFAS can be efficiently removed from water and then released again, effectively regenerating the electrode for further use. Unlike the activated carbon filter, which I have to destroy once it has become saturated with PFAS molecules, I can switch the metallocenes a thousand times, should I want to,’ said Markus Gallei, summarizing the significance of the research work.

Having laid the foundations, Frank Hartmann, Markus Gallei and their colleagues at the University of Illinois are now looking to upscale development to facilitate the removal of these highly persistent contaminants from our rivers and oceans.

Journal

ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces

DOI

10.1021/acsami.3c01670

Method of Research

Experimental study

Subject of Research

Not applicable

Article Title

Investigating the Electrochemically Driven Capture and Release of Long-Chain PFAS by Redox Metallopolymer Sorbents

Article Publication Date

28-Apr-2023