In a bid to understand why mosquitoes may be more attracted to one human than another, Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers say they have mapped specialized receptors on the insects’ nerve cells that are able to fine-tune their ability to detect particularly “welcoming” odors in human skin.

Credit: Johns Hopkins Medicine

In a bid to understand why mosquitoes may be more attracted to one human than another, Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers say they have mapped specialized receptors on the insects’ nerve cells that are able to fine-tune their ability to detect particularly “welcoming” odors in human skin.

Receptors on mosquito neurons have an important role in the insects’ ability to identify people who present an attractive source of a blood meal, according to Christopher Potter, Ph.D., associate professor of neuroscience at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “Understanding the molecular biology of mosquito odor-sensing is key to developing new ways to avoid bites and the burdensome diseases they cause,” he says.

Worldwide, mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, and West Nile virus afflict 700 million people and kill 750,000 each year. Although mosquito control efforts using nets and pesticides have helped reduce the toll, the development of better repellants to sabotage odorant attraction remains a priority.

Mosquitoes detect odors mostly through their antennae, and scientists have long observed that variations in odors, heat, humidity and carbon dioxide are factors in attracting mosquitos to some individuals more than others.

But, says Potter, the insects use multiple senses to find hosts. Anopheles gambiae, a family of mosquitoes that cause malaria, for example, has three types of receptors that stud the surface of neurons in their organs that sense odor: odorant, gustatory and ionotropic receptors.

Odorant receptors, says Potter, are the most well studied by scientists and are thought to help mosquitoes distinguish between animals and humans. Gustatory receptors detect carbon dioxide. Ionotropic receptors respond to acids and amines, compounds found on human skin. It is thought that different levels of particular acids on human skin might be a reason for some people to be more attractive to mosquitoes than others, says Potter.

Because of the potential for ionotropic receptors to guide a mosquito to prefer one type of human skin over another, Potter and postdoctoral researchers Joshua Raji and Joanna Konopka looked for them in mosquito antenna.

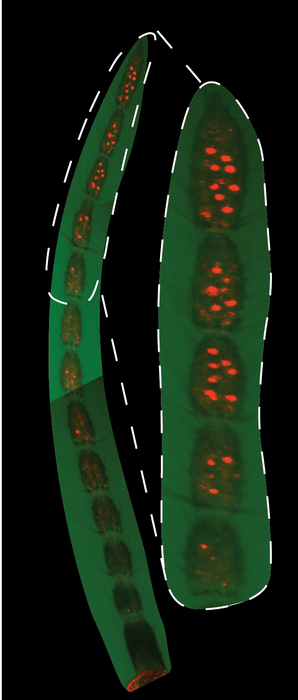

In a report published in the Feb. 28 issue of Cell Reports, the researchers described their search for the receptors in segmented tube-like antennae of 10 female and 10 male mosquitoes.

Bites to human skin come from female mosquitoes, although some research indicates that males are also attracted to human odors.

To find neurons expressing ionotropic receptors in the antennae, the researchers used a technique called fluorescent in situ hybridization, which pinpoints not the receptors themselves, but genetic material called RNA, a cousin of DNA. Finding RNA linked to ionotropic receptors means that the neurons are highly likely to be producing such receptors.

The scientists thought they’d find similar numbers of ionotropic receptor-laden neurons in each of the antennae segments, but they found the majority of ionotropic receptors in the distal (farthest from the head) part of the antennae.

They also found, however, that the antennae had more ionotropic receptors in the proximal (near the head) part of the mosquitoes. All told, Potter says his team’s experiments show that mosquito antennae are more complex than we previously thought them to be, says Potter.

Ionotropic receptors are known to work with “partner” receptors to respond to odors, “kind of like a dance partner,” says Potter. In the current study, the researchers were able to identify some pairings of receptors that predicted if an ionotropic receptor would respond to acids or amines. They verified these predictions by using genetic engineering to visualize the responses of an ionotropic receptor called Ir41c in the mosquito. Ir41c-expressing neurons were activated by one type of amine as predicted, but were inhibited (turned off) by a different type of amine.

Potter suspects that the ability of ionotropic receptor-expressing neurons to be both activated and inhibited by odors may allow mosquitoes to increase the range of responses ionotropic receptors can play in odor detection and in driving behaviors. Future studies, he says, will focus on identifying the specific ionotropic receptors that cause mosquitoes to be attracted to human odors.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01Al137078), the Department of Defense, the Johns Hopkins Postdoctoral Accelerator Award, the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute, the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council and Bloomberg Philanthropies.

DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112101

Journal

Cell Reports

DOI

10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112101