Efforts to fight disease-causing bacteria by harnessing their natural predators could be undermined when multiple species occupy the same space, according to a study by Dartmouth College researchers.

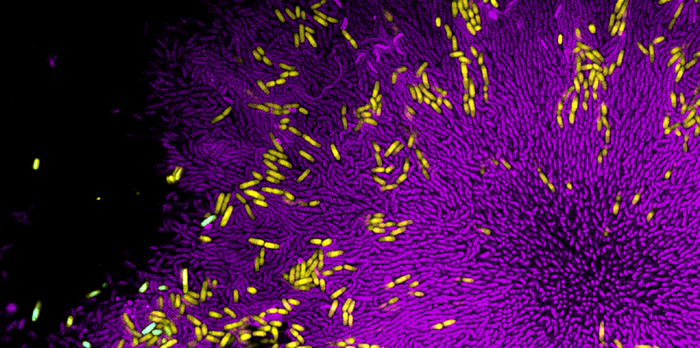

Credit: James Winans

Efforts to fight disease-causing bacteria by harnessing their natural predators could be undermined when multiple species occupy the same space, according to a study by Dartmouth College researchers.

When growing in mixed colonies, some harmful bacteria may be able to withstand attacks from the bacteria and viruses that target them by finding protection inside groups of rival species, according to a report published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The researchers found that the intestinal bacterium Escherichia coli became surrounded by tightly packed colonies of Vibrio cholerae — which causes the deadly disease cholera — when the species were grown together. These clusters protected E. coli from the bacteria Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus that preys on both species individually, but in the study could only kill the outer layer of V. cholerae. This left the unscathed cells of E. coli and V. cholerae insulated within the colonies free to multiply.

The findings add a new layer of complication to the development of biological antimicrobials, wherein bacteria-killing bacteria or viruses — known as bacteriophages — are deployed to fight infections, said corresponding author Carey Nadell, an assistant professor of biological sciences at Dartmouth College. These organisms can be more effective than antibiotics at penetrating bacterial colonies, or biofilms, and have emerged as a possible supplement or alternative to antibiotics. Bacteria worldwide have become more resistant to antibiotics due to the drugs’ overuse.

Most research on predatory bacteria and phages, however, has focused on liquid cultures or single-species biofilms, Nadell said. The Dartmouth study shows that the interactions between multiple bacterial species — which are more common in real life — can be difficult to predict from studying species in isolation. , Nadell and coauthors Benjamin Wucher and James Winans, Ph.D. candidates in biological sciences at Dartmouth,In a related study published in the journal PLoS Biology in December found that E. coli also could avoid the bacteriophage T7 when embedded in groups of V. cholerae.

“There were certain elements of our experiments that are closer to real life — a lot of infections are caused by bacteria living with other bacteria in a biofilm. They’re like a forest — they’re little ecosystems,” Nadell said.

“For E. coli, if it grew with V. cholerae, it could do better than on its own, but V. cholerae did worse. It’s fascinating that growing together had opposite effects on each species’ chances of survival,” he said. “Our research shows that the way prey populations can resist or not resist predators can be very different in multispecies conditions. The efficacy of bacteriophages and predatory bacteria to kill off harmful bacteria might depend on the other species their prey are living with, and on the biofilm structures they produce alone versus together.”

In the PNAS study, the protection afforded E. coli depended on how close the two bacteria were when they began growing. When sparsely populated, V. cholerae had ample room to form into tightly packed colonies that would encase E. coli, which does not grow as densely.

But when both species started out close together, E. coli prevented V. cholerae from producing its normal group structure. This disruption caused both species to become more vulnerable to death by B. bacteriovorus.

“When we put these species together, we observed biofilm properties we could not really predict from each alone that would have direct implications on the use of phages and predatory bacteria to kill them,” Nadell said. “Our work highlights the importance of studying other examples of multispecies biofilm structures. We feel confident that what we saw will apply to other cases, but it’s a question of when and to what extent.”

The paper, “Breakdown of Clonal Cooperative Architecture in Multispecies Biofilms and the Spatial Ecology of Predation,” was published online by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences DATE. The work was supported by the National Science Foundation (IOS 2017879 and MCB 1817352), the Simons Foundation (826672), the Human Frontier Science Program (RGY0077/2020), and a Gillman Fellowship and GAANN Fellowship from the Dartmouth College Department of Biological Sciences.

Journal

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

DOI

10.1073/pnas.2212650120

Method of Research

Experimental study

Subject of Research

Cells

Article Title

Breakdown of clonal cooperative architecture in multispecies biofilms and the spatial ecology of predation

Article Publication Date

2-Feb-2023