Inside the leading edge of a crawling cell, intricate networks of rod-like actin filaments extend toward the cell membrane at various angles, lengthening protein by protein. Upon impact, the crisscrossing rods glance off the membrane and bend as the collective force of myriad filaments pushes the cell forward.

Credit: Gregory Alushin

Inside the leading edge of a crawling cell, intricate networks of rod-like actin filaments extend toward the cell membrane at various angles, lengthening protein by protein. Upon impact, the crisscrossing rods glance off the membrane and bend as the collective force of myriad filaments pushes the cell forward.

How flexible these filaments are, and how effectively they recruit essential regulatory proteins to their cause, depends on the properties of the individual actin proteins composing them. Now, a new study in Nature provides high-resolution structures showing how two key biochemical states of actin work jointly with bending forces to determine how actin can interact with other proteins.

“When you add force to the mix, you see substantial changes,” says Rockefeller’s Gregory Alushin. “We provide clear evidence that these biochemical changes in actin are only readable through the mechanical properties of the filaments.”

Revisiting protein control

Actin filaments are long polymers of actin proteins, linked end to end. Actin proteins within a filament can exist in one of two important biochemical states. Actin newly added to the polymer contains a phosphate molecule and aged actin does not; otherwise, the two states are more or less identical. But actin-binding proteins can tell them apart, and they will bind or ignore a filament based on the state of its actin.

How actin-binding proteins distinguish between these states is a long-standing mystery. Some have proposed that phosphate somehow changes the shape of actin, allowing actin-binding proteins to pick it out of the crowd in vivo. Indeed, many enzymes can switch between shapes when other molecules latch onto them, in a process known as allosteric regulation. It made some sense to assume that actin would be no different.

But without knowing exactly what the two biochemical states of actin looked like, this was merely a guess. Alushin wondered whether there might be more to the story. “How proteins are controlled is an old question,” he says. “It had been a while since new ideas had been explored.”

Methodological leaps forward

Matthew Reynolds, a graduate student in Alushin’s lab, began working on high-resolution structures of each state. Upon examining these structures, where bound phosphate and water molecules were clearly resolved, the team found that the two actin states were still effectively indistinguishable. Whether or not actin was bound to phosphate, the structures featured nearly identical filament lattices and protein backbones. Had standard allosteric regulation been involved, there would have been marked changes in actin when it was bound to phosphate—the sort of major differences that regulatory proteins could have used to distinguish one type of actin from another. But the differences observed seemed far too minor for actin-binding proteins to be able to tell them apart.

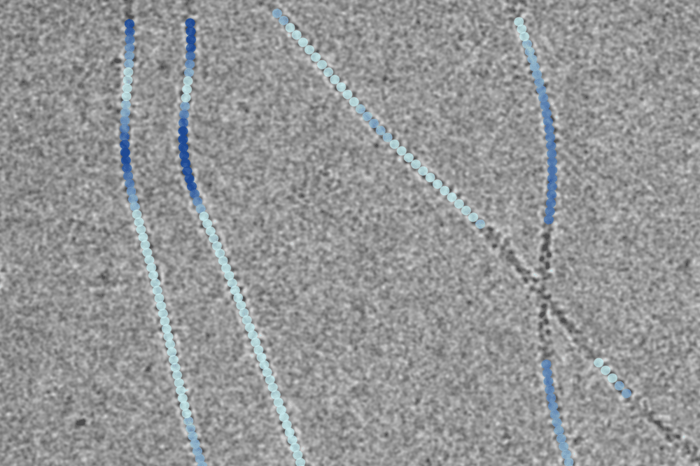

In search of an alternate explanation, the team developed a machine learning approach to find the relatively small number of bent filaments in their cryo-electron microscopy images in order to analyze their structures. They then determined structures of bent filaments in both biochemical states, where the scale of bending matched that found in cells when filaments glance off the membrane during locomotion. “Developing a way to capture this subset of images was crucial,” Alushin says. “This was a case where a methodological advance was needed for the scientific advance.”

When bent, actin that contained phosphate looked very different from actin without phosphate, such that actin-binding proteins would be able to easily distinguish between the two states.

“The change in the biochemical state of the filament biases the ways in which the filament can deform when force is applied,” Reynolds says.

A new model began to emerge: while an actin protein in a filament can flex in many ways when the polymer bends, that flexibility is limited when a phosphate cramps its style. Imagine a flexible tube containing little donuts, side by side. Some of the donuts have open holes, others have golf balls in their holes, but they are otherwise identical. When the tube bends, the donuts will all squish and change shape, but those with golf balls will deform differently than the others.

Similarly, the two states of actin are essentially indistinguishable before the filament bends but, once force is applied, those with phosphate squish differently than those without it. “What will matter is the deformability of the protein,” Alushin says. “If there’s a hole in the middle, it can flex in one way. If you fill that hole with phosphate, it won’t be able to squish in the same way.”

The results explain how actin-binding proteins can distinguish between biochemical states of actin, and they reveal a model of protein regulation that involves biochemical states and force working in concert. In future studies, Alushin hopes to investigate whether other proteins are similarly co-regulated.

“Our study of actin is a first glimpse into this phenomenon, but one limitation right now is that we don’t have structures of other force-responsive proteins in action,” he says. “It would be worthwhile looking into these proteins as it becomes technically possible to do so.”

Journal

Nature

DOI

10.1038/s41586-022-05366-w