One step forward, one step back for paleobiologists.

Credit: Credit Shuhai Xiao.

One step forward, one step back for paleobiologists.

Shuhai Xiao, a paleobiologist with the Department of Geosciences, part of the Virginia Tech College of Science, is part of a large, international team to take a new look at Saccorhytus, a roughly 535 million-year-old microfossil discovered in rocks in China by two researchers who were each once visiting professors in Xiao’s lab. The new find: Saccorhytus is not in fact the earliest representative of the deuterostomes, that is, animals with a secondary mouth – humans are part of this evolutionary lineage in case you’re wondering – but rather a protostome, or an animal with a primary mouth.

Most animals are bilaterally symmetrical. They have a left and a right side. These animals form two distinct groups, protostomes and deuterostomes. Humans and all vertebrate animals are part of the latter. Bugs, crabs, and clams are examples of the former.

“We are back to square one in the search for the earliest animal with a secondary mouth,” said Xiao, who is also an affiliated member of the Global Change Center, part of the Virginia Tech Fralin Life Sciences Institute. “The next oldest deuterostome fossil is nearly 20 million years younger.”

The results were published today in Nature, with the paper including researchers from Chang’an University, the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology (NIGPAS), the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, the First Institute of Oceanography of the Chinese Ministry of Natural Resource, Shandong University of Science and Technology, and Freie Universität Berlin, all located in China, and England’s University of Bristol as well as Switzerland’s Swiss Light Source.

Xiao said protostomes and deuterostomes likely separated from each other no later than 550 million years ago. “Primary-mouthers have a fossil record that goes back to 550 million years ago, but convincing fossils of secondary-mouthers are only estimated to be 515 million years old,” Xiao added. “This means that there is a large gap in the fossil record of deuterostomes, or our side of the animal tree. So we will continue our digging and searching for the real first deuterostome fossils.”

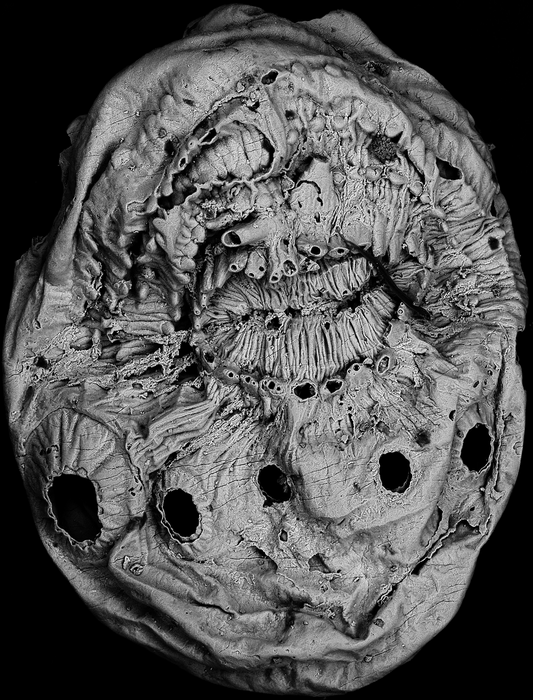

The Saccorhytus microfossils — seriously, these are tiny, about a millimetre in diameter — were discovered in 2012 in China by scientists Yunhuan Liu, now at Chang’an University, and later collaboration with Huaqiao Zhang, now at NIGPAS, recovered more material. Liu and Zhang were both visiting scientists at Xiao’s lab in Derring Hall at one point when they began the study of Saccorhytus, which resembles a spikey, wrinkly sack with a mouth surrounded by spines and holes that were interpreted by another research group as pores for gills – a primitive feature of deuterostomes, Xiao said.

Together with researchers from China, Germany, and the United Kingdom, the research team more recently dug for additional specimens of Saccorhytus and scored big. Once believed to be rare, the team recovered hundreds of specimens, many much better preserved than any seen before, providing new insights into the anatomy and evolutionary affinity of Saccorhytus, Xiao said.

Tons of rocks holding the creatures inside were dissolved with a vinegar solution, and the remaining sand was then picked over. The team then used a particle accelerator at the Swiss Light Source in Switzerland to shine intense X-rays on the fossils in order to obtain detailed images. With hundreds of these X-ray images, each at a slightly different angle, a supercomputer was used to create 3D digital models, which revealed the tiny features of Saccorhytus’ internal and external structures.

A man with a salt and pepper goatee and large white hat looks into his own cell phone camera.

“Some of the fossils are so perfectly preserved that they look almost alive. Saccorhytus was a curious beast, with a mouth but no anus and rings of complex spines around its mouth,” Liu said.

Added Zhang, “The digital models showed that pores once interpreted as gills are actually broken spines, striking down the only piece of evidence in support of a deuterostome interpretation.”

If not a deuterostome, what is Saccorhytus? “We considered lots of alternative groups that Saccorhytus might be related to, including the corals, anemones, and jellyfish, which also have a mouth but no anus. Our comprehensive analysis led to a relationship with the arthropods and their kin, the group to which insects, crabs, and roundworms belong,” said Philip Donoghue, a co-author from University of Bristol.

The findings, according to Xiao, were unexpected “because the arthropod group has a through-gut, extending from mouth to anus.” He added, “Saccorhytus’s membership of the group indicates that it has regressed in evolutionary terms, dispensing with the anus its ancestors would have inherited.

There’s still much to uncover. Perhaps more than what has already been discovered. Michael Steiner, another co-author from Shandong University of Science and Technology and Freie Universität Berlin, asked how Saccorhytus would have lived: “floating in the sea or living among sand grains?” Further, were the microscopic creatures’ spines used for “deterring predators or for stabilizing the organism within the sea floor?” Perhaps, the answer is both.

Xiao and team intended to find the answers.

Journal

Nature

DOI

10.1038/s41586-022-05107