AUGUSTA, Ga. (Aug. 11, 2022) – Unnatural, direct connections between arteries and veins, like an access point for kidney dialysis and using a vein to bypass a blockage in a coronary artery, are made to save a life.

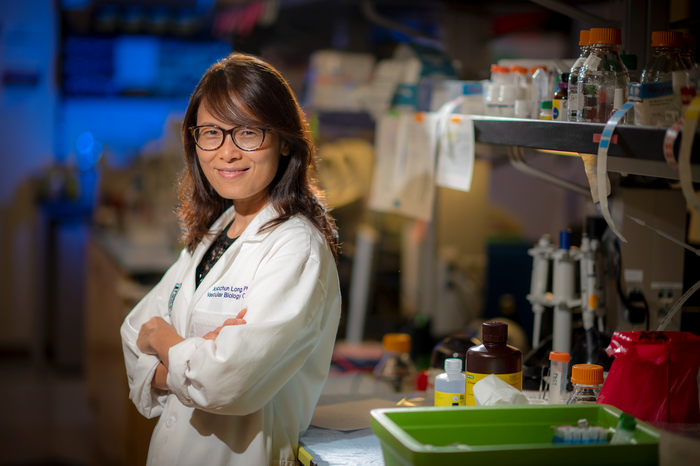

Credit: Michael Holahan, Augusta University

AUGUSTA, Ga. (Aug. 11, 2022) – Unnatural, direct connections between arteries and veins, like an access point for kidney dialysis and using a vein to bypass a blockage in a coronary artery, are made to save a life.

But, the vein, unaccustomed to and not really built to handle the high volume, high pressure of the blood flowing through our arteries, can rapidly narrow in response, causing the bypass graft or dialysis access point to fail.

Dr. Xiaochun Long, molecular biologist in the Vascular Biology Center at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, is working to literally strengthen the walls of these veins so they can function more like arteries to better ensure the veins’ success for patients in their unfamiliar new role.

Long just received a $400,000 Established Investigator Award from the American Heart Association to support her work to ultimately make the middle layer of veins — comprised primarily of one layer of smooth muscle cells that give them shape and strength — more like the thicker middle of arteries, which are built to handle the pressure of the heart pumping blood into them.

“Once you connect the artery to the vein, the vein will change,” says Long. “We want to help control smooth muscle cell behavior to help the vein better adapt to the arterial dynamic.”

To find ways to improve how these arteriovenous fistulas, or AVF, for dialysis and bypass grafts for the heart mature, we first need to better understand how the vein adapts, Long says.

Long and her team know that the smooth muscle cells in the blood vessel walls are key to sensing the walls being stretched in response to the increased pressure and volume. But what they do in response is less well understood.

Her lab has early evidence that in the vein, the smooth muscle cells move from their typically quiescent state to proliferating. Smooth muscle cells, typically not as aggressive at contracting in the veins as they are in the arteries, where they continuously help push blood out to the body, surprisingly retain the ability to contract as they start to change, Long says.

In looking at how they transition, her genome-wide studies have uncovered two related genes known to play an important role in smooth muscle cell differentiation — basically how smooth muscle cells are made from stem cells — that also are important to healthy maturation of the under-stress veins.

She has evidence that myocardin-related transcription factor, or MRTF A and B (also known as MKL1 and 2), respond to the newfound stretch by activating other genes that enable the smooth muscle cells to proliferate, differentiate and organize and are key early on to the proper maturation of an AVF, for example.

A deficiency of these transcription factors, conversely, impedes the ability of the smooth muscle cells to properly shore up the vein wall in response to the added pressure. While veins have some expression of these genes, they have less than arteries, and when it comes to bulking up the smooth muscle layer of veins, they need more at the right time, Long says.

Her many goals with the new grant include looking further at the role of these key transcription factors as well as other cell types, including the endothelial cells which line blood vessels, in enabling the smooth muscle cells to help veins mature.

The work could one day lead to therapies to turn up the expression of genes that enable a successful transition.

Long knows that these unnatural connections can work, because the bypasses and fistulas do work for a lot of people. And, she has done studies directly connecting the big jugular vein to the big carotid artery and seen vein walls get stronger in response. Genetics likely are a factor in why the connections work for some and not for others, she says.

An AVF, considered the best choice for dialysis, according to the National Kidney Foundation, is created surgically with the idea of devising a long-term path for more blood to flow through the dialysis machine for cleansing during a dialysis session and they are generally associated with lower infection rates.

However a high rate of the fistulas created don’t mature sufficiently so they can’t be used. Conditions like diabetes can increase failure risk. “It’s a very big problem for patients and caregivers alike,” Long says.

To treat atherosclerosis, a patient’s veins often are used to bypass arterial blockages in their heart and/or legs and studies indicate, for example, that about half of vein grafts for the heart fail 5 to 10 years after surgery and 20-40% within the first year.

The bottom line is that the veins can become occluded, in the case of heart bypass surgery, much like the clogged vessels they have been used to bypass. More typically, veins are essentially immune to the familiar build up of plaque that is the most common cause of heart disease, the nation’s number one killer.

Normally blood flows from the arteries to the capillaries, the smallest blood vessels in the body, which help slow blood flow and volume down before reaching the veins — like going from a four lane road down to two lanes. A primary function of thinner-walled capillaries is to share oxygen and nutrients with body tissue.

Vascular smooth muscle cells are the primary component of the middle and thickest layer of the three-layer artery wall called the tunica media. In contrast, all three layers of the vein wall are thinner. But the vein’s central passageway, called the lumen, is generally a lot bigger. Long notes that vascular smooth muscle cells in the arteries and veins are not identical in their natural state, which is part of the problem, and one of many things she wants to better understand is their differences.

“Without smooth muscle cells, blood vessels cannot contract,” Long says, and they take many of their cues on what they need to do from the endothelial cells that line blood vessels and come in direct contact with the blood.

But vascular smooth muscle cells also can contribute to disease in the arteries. In response to the early injury of atherosclerosis, they can again switch from quiescent mode, become activated and start moving to the inside of the lumen in an apparent attempt to help heal the artery. Long and others have seen the cells instead become an early contributor to the disease. There also is evidence that hypertension triggers this unhealthy shift in vascular smooth muscle cells.

Arteriovenous fistulas or malformations also can occur spontaneously throughout the body and brain and may require a procedure to help better secure or close the abnormal passageways which are subject to rupture.