Which genes control the defining features that make us look as we do? And how do they make it happen?

Credit: Bier Lab, UC San Diego

Which genes control the defining features that make us look as we do? And how do they make it happen?

In 1990, University of California San Diego biologist William McGinnis conducted a seminal experiment that helped scientists unravel how high-level control genes called Hox genes shape our appearance features. The “McGinnis experiment” helped pave the way for understanding the role of Hox genes in determining the uniform appearances of species, from humans to chimpanzees to flies.

McGinnis, a professor emeritus of Cell and Developmental Biology and former dean of the Division of Biological Sciences, helped discover a defining DNA region that he termed the “homeobox,” a sequence within genes that directs anatomical development. Since the now-famous McGinnis experiment, evolutionary and developmental biologists have pondered how these highly influential Hox genes determine the identities of different body regions.

More than three decades later, a study published Nov. 10 in Science Advances and led by Ankush Auradkar, a UC San Diego postdoctoral scholar mentored by coauthor McGinnis and study senior author Ethan Bier, helps answer questions about how Hox genes function.

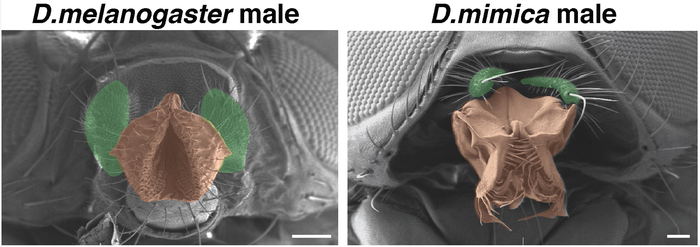

The now-textbook McGinnis experiment tested whether the proteins produced by a human or mouse Hox gene could function in flies. Following in these footsteps, the new study leveraged modern CRISPR gene editing to investigate whether all aspects of Hox gene function, which consists of both protein coding and control regions, could be replaced in a common laboratory fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) with its counterpart from a rarer Hawaiian cousin (Drosophila mimica), which has a very different face.

The gene in question, proboscipedia, would plainly reveal itself since it directs the formation of strikingly different mouth parts—smooth and spongy in D. mel but more grill-like (resembling the face of the alien in Predator science fiction films) in D. mim.

Study coauthor Emily Bulger first collected the notoriously difficult-to-breed D. mim samples from Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park, along with the only native fruit (Sapindus saponaria – Hawaiian soapberry) that the insects are known to eat, in order to establish a temporary colony in Bier’s laboratory. Auradkar then collaborated with coauthor Sushil Devkota to decipher the genome sequence of the D. mim proboscipedia gene, which was nearly 44,000 bases long. The researchers then deleted the D. mel proboscipedia gene and replaced it with the D. mim version of the same.

As McGinnis had predicted, the new results revealed that the graceful facial structure of D. mel emerged as the “winner” over the rough features of D. mim. One trait of D. mim, however, did surface during the experiment: Sensory organs called maxillary palps that stick out from the face in D. mel instead ran parallel to feeding mouthparts as they do in D. mim. Auradkar used sophisticated genetic tools to determine the basis for this difference and tracked it down to a change in the pattern by which the proboscipedia gene is activated (control region changes).

The experiment’s results help answer longstanding questions about whether Hox genes function as “master” regulatory genes that dictate different body parts in organisms. Or, as McGinnis proposed, whether Hox genes instead provide abstract positional codes and serve as scaffolds for downstream genes that best benefit the organism. Other than the maxillary palps, the new results demonstrated that McGinnis’ scaffolding idea proved to be the case.

McGinnis says that beyond the implications for evolutionary biology, the results could help explain developmental issues rooted in fundamental human genetic processes.

“These fly studies provide a window into deep evolutionary time and inform us about the mechanisms by which body plans change during evolution,” said Bier. “These insights may lead to a better of understanding of processes tied to congenital birth defects in humans. With the advent of powerful new CRISPR-based genome editing systems for human therapy on the horizon, new strategies might be formulated to mitigate some of the effects of these often debilitating conditions.”

###

According to Bier, these investigations also provide an example of the intimate connection between the support of basic science and human welfare. The paper was authored by Ankush Auradkar, Emily Bulger, Sushil Devkota, William McGinnis and Ethan Bier.

Journal

Science Advances

DOI

10.1126/sciadv.abk1003

Method of Research

Experimental study

Subject of Research

Animals

Article Title

Dissecting the evolutionary role of the Hox gene proboscipedia in Drosophila mouthpart diversification by full locus replacement

Article Publication Date

10-Nov-2021

COI Statement

Professor Ethan Bier has equity interest in two companies he co-founded: Synbal Inc. and Agragene, Inc., which may potentially benefit from the research results. He also serves on Synbal’s board of directors and the scientific advisory board for both companies.