Credit: RIKEN

Billions of cells in our bodies die every day in an important process called apoptosis. Now, researchers at the RIKEN Brain Science Institute have mapped out a sequence of events that are necessary for apoptosis to occur properly. Published in eLife, the study focuses on the protein IRBIT and how its action near mitochondria in our cells can set off a chain reaction that leads to programmed cell death.

Disruptions in proper apoptosis can lead to serious medical consequences. As team leader Katsuhiko Mikoshiba explains, "Excessive apoptosis in the brain is associated with several neurodegenerative diseases, while impaired apoptosis is related to some cancers and tumor formation."

Events that happen inside our cells are often controlled by interactions between proteins and modifications of proteins that change how they can interact with each other. Mikoshiba and his team have already shown that apoptosis in neurons can be initiated when certain proteins binds to IP3 receptors. In their new study, the team investigated IRBIT, another protein commonly found in the brain that can bind to the IP3 receptor.

In a series of studies, the researchers showed that the presence of IRBIT promoted normal apoptosis. "We were actually quite surprised," notes first author Benjamin Bonneau. "We initially expected that IRBIT would function to suppress cell death."

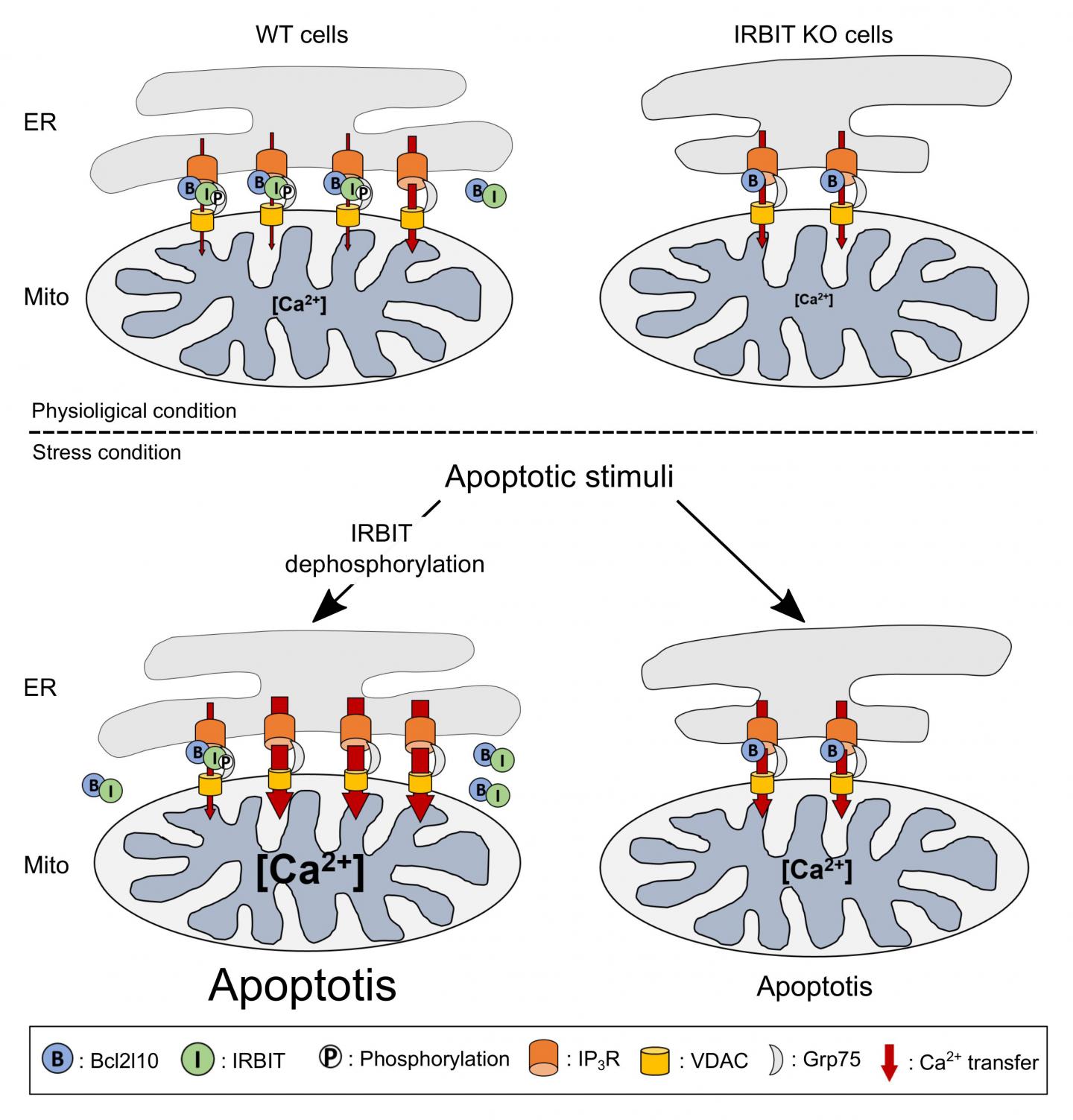

The reason for this prediction was that IRBIT has been primarily described as a protein that reduces cellular calcium levels, a phenomenon that can lead to cell death. Additionally, IRBIT is located in the same parts of the body–including the developing nervous system–as Bcl2l10, another protein that is known to reduce apoptosis and which also binds to the same region of the IP3 receptor as IRBIT. The key factor in this process is the flow of calcium ions between two organelles within a cell–the ER and mitochondria. When Bcl2l10 is attached to the IP3 receptor located in the ER membrane, it reduces the flow of calcium into the mitochondria, which prevents apoptosis.

In their new study, the team first showed that IRBIT and Bcl2l10 naturally attach to different places on the IP3 receptor, and that they attach to each other. This is why they initially thought that they work together to prevent apoptosis. However, further testing revealed an important event that always preceded apoptosis–IRBIT loses a phosphate group. Protein function is often altered through small additions or subtractions. The team showed that in this case, the loss of the phosphate group prevents IRBIT from staying attached to the IP3 receptor. Instead it moves away from the ER, and drags Bcl2l10 with it. When this happens, the team saw that without Bcl2l10, calcium flow into the mitochondria increased, which led to cell death.

Understanding IRBIT's role in facilitating apoptosis has implications for treating cancer that is associated with low levels of IRBIT expression. Bonneau notes that, "Because reduced IRBIT expression may contribute to tumor formation, the next step is to determine to what extent modulating IRBIT expression contributes to cancer formation, and if this is the case, what organs are the most sensitive.

Mikoshiba adds, "Neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington's disease and Parkinson's disease are characterized by excessive apoptosis. Knowing IRBIT's involvement gives us a new target for investigation. As IRBIT is highly expressed in the brain, the chances are good that we will be able to find a connection, which could lead to new treatment possibilities."

###

Reference:

Bonneau B, Ando H, Kawaai K, Hirose M, Takahashi-Iwanaga H, Mikoshiba K (2016). IRBIT controls apoptosis by interacting with the Bcl-2 homolog, Bcl2110, and by promoting ER-mitochondria contact. eLife. doi: 10.7554/eLife19896

Media Contact

Adam Phillips

[email protected]

@riken_en

http://www.riken.jp/en/

############

Story Source: Materials provided by Scienmag