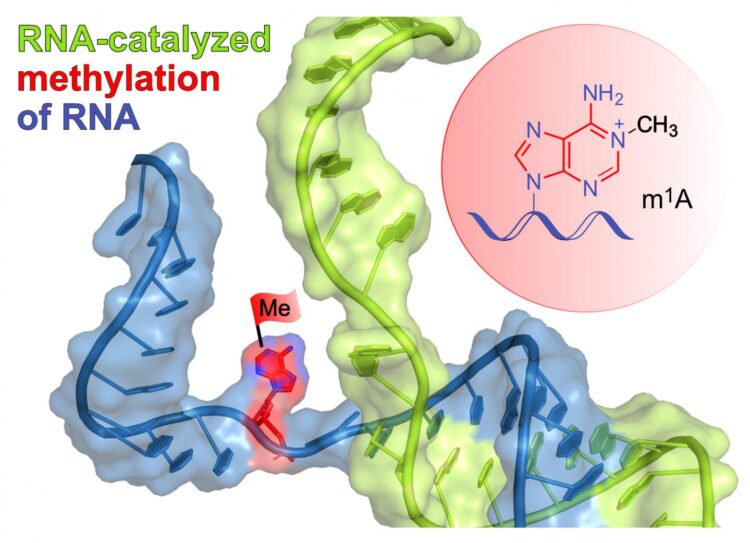

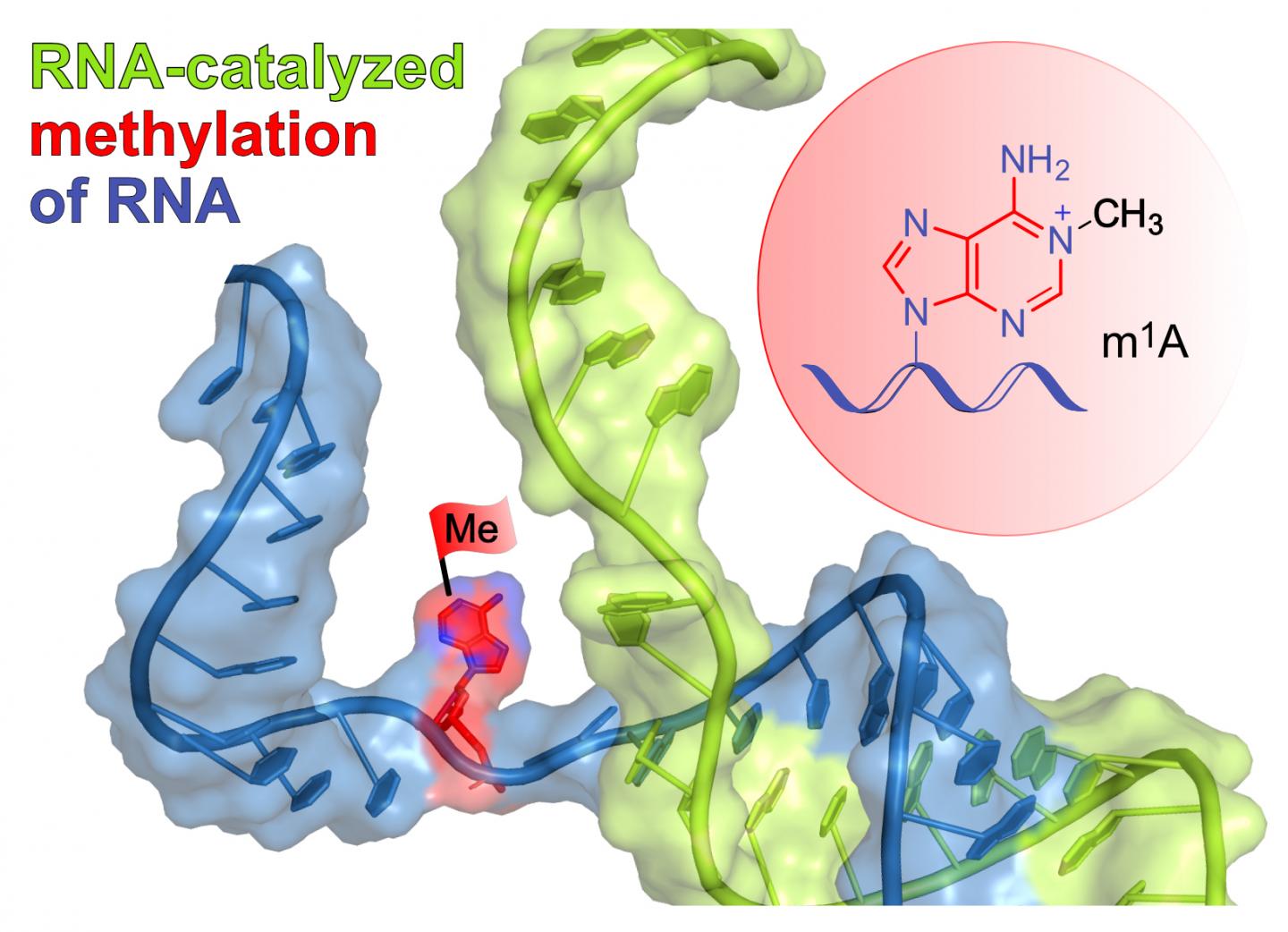

Credit: Image: Claudia Hoebartner / University of Wuerzburg

Enzymes enable biochemical reactions that would otherwise not take place on their own. In nature, it is mostly proteins that function as enzymes. However, other molecules can also perform enzymatic reactions – for example ribonucleic acids, RNAs. These are then called ribozymes.

In this field, the research group of chemistry professor Claudia Höbartner is now reporting a scientific breakthrough: Her team at Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg (JMU) in Bavaria, Germany, has developed a ribozyme that can attach a very specific small chemical change at a very specific location in a target RNA.

More precisely: the ribozyme transfers a single methyl group to an exactly defined nitrogen atom of the target RNA. This makes it the first known methyl transferase ribozyme in the world. Accordingly, Höbartner’s group has given it the short name MTR1.

In the journal Nature the group presents details about the new ribozyme. In the target RNA, it produces the methylated nucleoside 1-methyladenosine (m1A). The methyl group is transferred from a free methylated guanine nucleobase (O6-methylguanine, m6G) in a binding pocket of the ribozyme.

Ribozymes in evolution

The ribozyme discovered at the JMU Institute of Organic Chemistry sheds light on an interesting aspect of evolution. According to the “RNA world hypothesis”, RNA was one of the first information-storing and enzymatically active molecules. Ribozymes similar to those developed by Claudia Höbartner and her team may have produced methylated RNAs in the course of evolution. This in turn may have led to a greater structural and thus functional diversity of RNA molecules.

In nature, methyl groups are installed on RNAs by specialised protein enzymes. These proteins use cofactors that contain RNA-like components. “It is reasonable to assume that these cofactors could be evolutionary ‘leftovers’ of earlier enzymatically active RNAs. Our discovery may therefore mimic a ribozyme that has possibly been lost in nature a long time ago,” says Claudia Höbartner.

In the laboratory, new or naturally extinct ribozymes can be found by a method called in vitro evolution. “It starts from many different sequences of synthetic RNA, and is analogous to finding a needle in the haystack”, says co-author Mohammad Ghaem Maghami, a postdoctoral researcher in the Höbartner group.

New ribozyme also acts on natural RNA

The authors have also been able to show that MTR1 can install a single methyl group not only on synthetic RNA structures but also on natural RNA strands found in cells.

This news is likely to attract great attention from cell biologists, among others. The reason for this is that the methylation of RNA can be considered as a biochemical on or off switch. It has a key role in the functioning of RNA structures and can control many life processes in the cell.

The newly developed ribozyme MTR1 is expected to be a useful tool for a wide range of research areas in the future. “For example, it could help to better understand the interaction of methylation, structure, and function of RNA,” explains JMU PhD student Carolin Scheitl, the first author of the publication in Nature.

The next steps of the researchers

Many new projects will build on these results. Höbartner’s group intends to solve the structure of their new ribozyme and reveal the detailed chemical mechanism of the RNA-catalyzed methylation. With the methods now established, her team will also be able to develop ribozymes for a variety of other reactions.

According to the JMU professor, these ribozymes also offer an excellent possibility to control Watson-Crick base pairing and to install fluorescent labels for RNA imaging.

###

Media Contact

Prof. Dr. Claudia Höbartner

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.