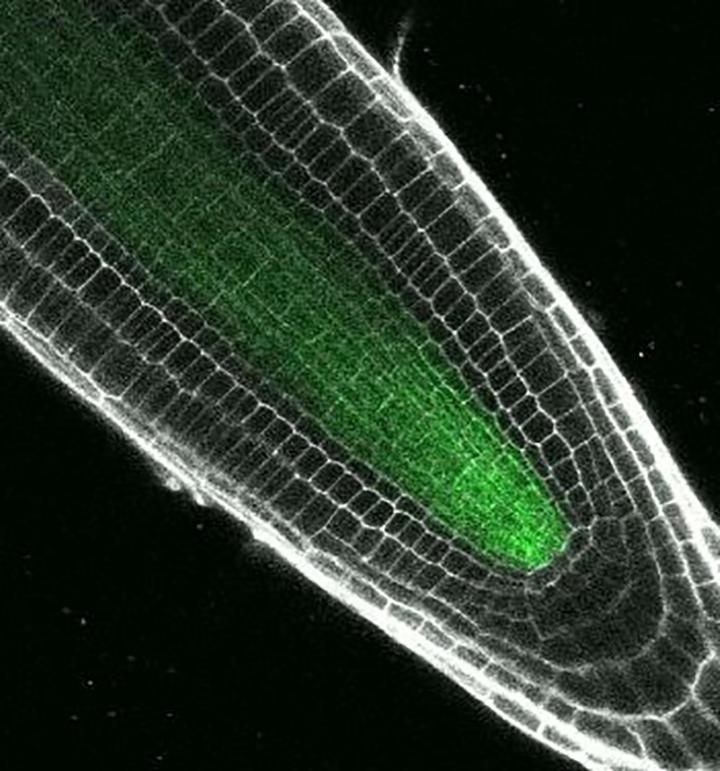

Credit: Photo by Erin Sparks, Duke University

v

DURHAM, N.C. — As a growing plant extends its roots into the soil, the new cells that form at their tips assume different roles, from transporting water and nutrients to sensing gravity.

A new study points to one way by which these newly-formed cells, which all contain the same DNA, take on their special identities.

Researchers have identified a set of DNA-binding proteins in the roots of the plant Arabidopsis thaliana that work in combination to help precursor cells selectively read different parts of the same genetic script and acquire their different fates.

Led by researchers at Duke University, the study offers clues to a longstanding question in developmental biology, namely how plants and animals make so many types of cells from the same set of instructions.

The findings appear in the Dec. 5 issue of the journal Developmental Cell.

Plant and animal tissues start off as immature cells called stem cells. In order for these unspecialized cells to acquire the characteristics that make a leaf cell different from a root cell or a blood cell different from a muscle cell, they must turn on different subsets of genes to produce the proteins responsible for each cell type's distinctive properties.

"It's a chicken and egg problem," said first author Erin Sparks, a post-doctoral associate with Duke biology professor Philip Benfey. How do cells start to turn on different genes if they're all the same to begin with?

Sparks, Benfey and colleagues think they've identified one way in Arabidopsis.

A cousin of cabbage and radishes, Arabidopsis is the laboratory mouse of the plant world. The plant's tiny threadlike roots are built from roughly 15 types of cells, each with its own set of duties.

Only some of the plant's 30,000 genes are active in a given root cell at a given time, thanks to proteins called transcription factors that turn genes on and off as needed.

The study focused on a key transcription factor in Arabidopsis called "Short-root," so named because plants with harmful versions of the Short-root gene have stunted roots.

Over the past several decades, Benfey and colleagues have shown that Short-root acts as a master switch, initiating the process that transforms general purpose precursor cells into the specialized cells found in certain parts of the Arabidopsis root.

Previous research found that Short-root activates other transcription factors as well, creating a cascade in which each gene-regulating protein controls the next in the root development pathway.

Researchers have identified many of Short-root's gene targets, but weren't sure what controlled the Short-root master switch itself to kick off the cascade.

The answer, the new study shows, lies in not one but multiple DNA-binding proteins.

Sparks used a modified version of a technique called a yeast one-hybrid assay to identify more than 20 root proteins that would likely bind to the promoter region of the Short-root gene to control its activity.

Sure enough, plants with mutant versions of these DNA-binding proteins produced root cells with altered levels of Short-root.

Some binding proteins work by turning on the Short-root gene and others by shutting it down. Though most of these proteins are present in multiple root cell types, the researchers found, their statistical models and experiments in living plants suggest the combined effect is to activate the Short-root master switch in some cells but not others.

"It's all about the balance between activators and repressors," Sparks said. "It's their coordinated effect that turns Short-root on or off."

Similar mechanisms could initiate cell differentiation in other plant species too, Sparks said. If so, it could make cell fate more resilient to random mutations in a plant's genetic code, even when such changes keep some gene-regulating proteins from binding their intended DNA targets.

"By spreading the responsibility we can buffer the system against small changes," Sparks said.

###

Other authors include Colleen Drapek, Ning Shen, Jessica Hennacy, Jingyuan Zhang, Jalean Petricka, Alexander Hartemink and Raluca Gordân of Duke; Allison Gaudinier, Gina Turco, Jessica Foret and Siobhan Brady of the University of California-Davis; Song Li of Virginia Tech, and Mitra Ansariola and Molly Megraw of Oregon State University.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (IOS-1021619, DGE-1148897), the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM043778, GM097188, GM086976), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (GBMF3405).

CITATION: "Establishment of Expression in the SHORTROOT-SCARECROW Transcriptional Cascade through Opposing Activities of Both Activators and Repressors," Erin Sparks, et al. Developmental Cell, Dec. 5, 2016. DOI: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.09.031

Media Contact

Robin Smith

[email protected]

919-681-8057

@DukeU

http://www.duke.edu

############

Story Source: Materials provided by Scienmag