A study of mice in a semi-natural setting shows how the hormone oxytocin can amplify aggression as well as friendliness

Credit: Weizmann Institute of Science

During the pandemic lockdown, as couples have been forced to spend days and weeks in one another’s company, some have found their love renewed while others are on their way to divorce court. Oxytocin, a peptide produced in the brain, is complicated in that way: a neuromodulator, it may bring hearts together or it can help induce aggression. That conclusion arises from unique research led by Weizmann Institute of Science researchers in which mice living in semi-natural conditions had their oxytocin producing brain cells manipulated in a highly precise manner. The findings, which were published in Neuron, could shed new light on efforts to use oxytocin to treat a variety of psychiatric conditions, from social anxiety and autism to schizophrenia.

Much of what we know about the actions of neuromodulators like oxytocin comes from behavioral studies of lab animals in standard lab conditions. These conditions are strictly controlled and artificial, in part so that researchers can limit the number of variables affecting behavior. But a number of recent studies suggest that the actions of a mouse in a semi-natural environment can teach us much more about natural behavior, especially when we mean to apply those findings to humans.

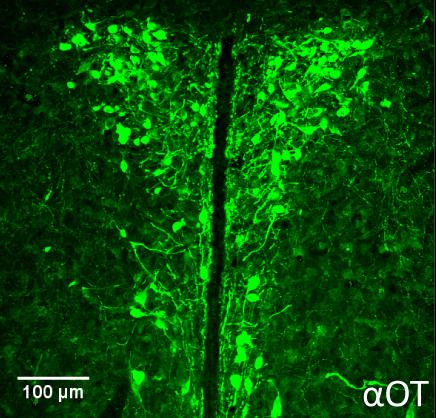

Prof. Alon Chen’s lab group in the Institute’s Neurobiology Department have created an experimental setup that enables them to observe mice in something approaching their natural living conditions – an environment enriched with stimuli they can explore – and their activity is monitored day and night with cameras and analyzed computationally. The present study, which has been ongoing for the past eight years, was led by research students Sergey Anpilov and Noa Eren, and Staff Scientist Dr. Yair Shemesh in Prof. Chen’s lab group. The innovation in this experiment, however, was to incorporate optogenetics – a method that enables researchers to turn specific neurons in the brain on or off using light. To create an optogenetic setup that would enable the team to study mice that were behaving naturally, the group developed a compact, lightweight, wireless device with which the scientists could activate nerve cells by remote control. With the help of optogenetics expert Prof. Ofer Yizhar of the same department, the group introduced a protein previously developed by Yizhar into the oxytocin-producing brain cells in the mice. When light from the wireless device touched those neurons, they became more sensitized to input from the other brain cells in their network.

“Our first goal,” says Anpilov, “was to reach that ‘sweet spot’ of experimental setups in which we track behavior in a natural environment, without relinquishing the ability to ask pointed scientific questions about brain functions.”

Shemesh adds that, “the classical experimental setup is not only lacking in stimuli, the measurements tend to span mere minutes, while we had the capacity to track social dynamics in a group over the course of days.”

Delving into the role of oxytocin was sort of a test drive for the experimental system. It had been believed that this hormone mediates pro-social behavior. But findings have been conflicting, and some have proposed another hypothesis, termed “social salience” stating that oxytocin might be involved in amplifying the perception of diverse social cues, which could then result in pro-social or antagonistic behaviors, depending on such factors as individual character and their environment.

To test the social salience hypothesis, the team used mice in which they could gently activate the oxytocin-producing cells in the hypothalamus, placing them first in the enriched, semi-natural lab environments. To compare, they repeated the experiment with mice placed in the standard, sterile lab setups.

In the semi-natural environment, the mice at first displayed heightened interest in one another, but this was soon accompanied by a rise in aggressive behavior. In contrast, increasing oxytocin production in the mice in classical lab conditions resulted in reduced aggression. “In an all-male, natural social setting, we would expect to see belligerent behavior as they compete for territory or food,” says Anpilov. “That is, the social conditions are conducive to competition and aggression. In the standard lab setup, a different social situation leads to a different effect for the oxytocin.”

If the “love hormone” is more likely a “social hormone,” what does that mean for its pharmaceutical applications? “Oxytocin is involved, as previous experiments have shown, in such social behaviors as making eye contact or feelings of closeness,” says Eren, “but our work shows it does not improve sociability across the board. Its effects depend on both context and personality.” This implies that if oxytocin is to be used therapeutically, a much more nuanced view is needed in research: “If we want to understand the complexities of behavior, we need to study behavior in a complex environment. Only then can we begin to translate our findings to human behavior,” she says.

###

Participating in this research were scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Psychiatry in Munich, including research students Asaf Benjamin and Stoyo Karamihalev, staff scientist Dr. Julien Dine and postdoctoral fellow Dr. Oren Forkosh of the Chen lab; Prof. Shlomo Wagner and postdoctoral fellow Dr. Hala Harony-Nicolas of Haifa University; Prof. Inga Neumann and research student Vinicius Oliveira of Regensburg University, Germany; and electrical engineer Avi Dagan.

Prof. Alon Chen’s research is supported by the Ruhman Family Laboratory for Research in the Neurobiology of Stress; the Perlman Family Foundation, Founded by Louis L. and Anita M. Perlman; the Fondation Adelis; Bruno Licht; and Sonia T. Marschak. Prof. Chen is the incumbent of the Vera and John Schwartz Professorial Chair in Neurobiology.

Prof. Ofer Yizhar’s research is supported by the Ilse Katz Institute for Material Sciences and Magnetic Resonance Research; the Adelis Brain Research Award; and Paul and Lucie Schwartz, Georges and Vera Gersen Laboratory.

The Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, is one of the world’s top-ranking multidisciplinary research institutions. Noted for its wide-ranging exploration of the natural and exact sciences, the Institute is home to scientists, students, technicians and supporting staff. Institute research efforts include the search for new ways of fighting disease and hunger, examining leading questions in mathematics and computer science, probing the physics of matter and the universe, creating novel materials and developing new strategies for protecting the environment.

Media Contact

Gizel Maimon

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/