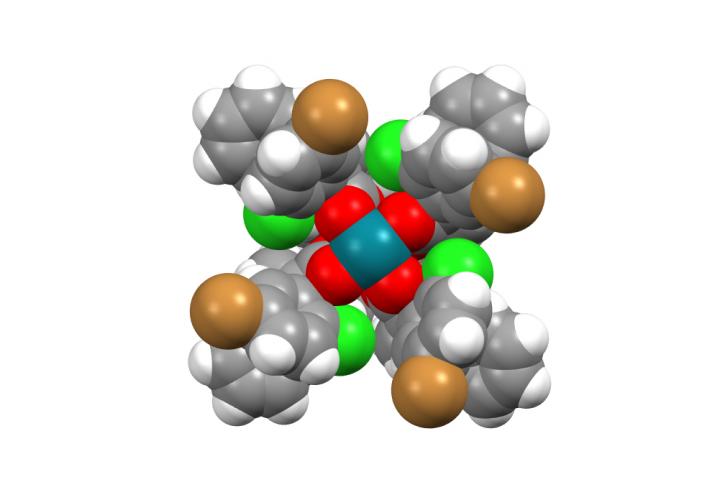

Credit: Davies Lab/Emory University

After helping develop a new approach for organic synthesis — carbon-hydrogen functionalization — scientists at Emory University are now showing how this approach may apply to drug discovery. Nature Catalysis published their most recent work — a streamlined process for making a three-dimensional scaffold of keen interest to the pharmaceutical industry.

“Our tools open up whole new chemical space for potential drug targets,” says Huw Davies, Emory professor of organic chemistry and senior author of the paper.

Davies is the founding director of the National Science Foundation’s Center for Selective C-H Functionalization, a consortium based at Emory and encompassing 15 major research universities from across the country as well as industrial partners.

Traditionally, organic chemistry has focused on the division between reactive molecular bonds and the inert bonds between carbon-carbon (C-C) and carbon-hydrogen (C-H). The inert bonds provide a strong, stable scaffold for performing chemical synthesis with the reactive groups. C-H functionalization flips this model on its head, making C-H bonds become the reactive sites.

The aim is to efficiently transform simple, abundant molecules into much more complex, value-added molecules. Functionalizing C-H bonds opens new chemical pathways for the synthesis of fine chemicals — pathways that are more direct, less costly and generate less chemical waste.

The Davies lab has published a series of major papers on dirhodium catalysts that selectively functionalize C-H bonds in a streamlined manner.

The current paper demonstrates the power of a dirhodium catalyst to efficiently synthesize a bioisostere of a benzene ring. A benzene ring is a two-dimensional (2D) molecule and a common motif in drug candidates. The bioisostere has similar biologicial properties to a benzene ring. It is a different chemical entity, however, with a 3D structure, which opens up new chemical territory for drug discovery.

Previous attempts to exploit this bioisostere for biomedical research have been hampered by the delicate nature of the structure and the limited ways to make them. “Traditional chemistry is too harsh and causes the system to fragment,” Davies explains. “Our method allows us to easily achieve a reaction on a C-H bond of this bioisostere in a way that does not destroy the scaffold. We can do chemistry that no one else can do and generate new, and more elaborate, derivatives containing this promising bioisostere.”

The paper serves as proof of principle that bioisosteres can serve as fundamental building blocks to generate an expanded range of chemical entities. “It’s like getting a new Lego shape in your kit,” Davies says. “The more Lego shapes you have, the more new and different structures you can build.”

###

Zachary Garlets, a former member of the Davies lab who currently works for the biopharmaceutical firm Bristol-Myers Squibb, is first author of the paper. The project was a collaboration between the Davies lab and computational chemists from UCLA (Jacob Sanders and K.N. Houk) and medicinal chemists from Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research (Hasnain Malik and Christian Gampe).

The paper follows another recent demonstration of the potential for generating novel scaffolds relevant to pharmaceutical research using the method. That work, a collaboration between Emory chemists and AbbVie, was published in the journal Chem.

Media Contact

Carol Clark

[email protected]

404-727-0501

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.